Life Risk Insurance – a challenge to the life industry: managing for long term portfolio health

Ian Laughlin, Deputy Chairman – Insights Session at Actuaries Institute, Sydney

The life insurance industry in Australia has a long and proud history. It has survived depressions, recessions and wars. It has been a major investor in the country (providing capital, and developing property and infrastructure). It has provided countless people with financial protection, savings, investments and peace of mind.

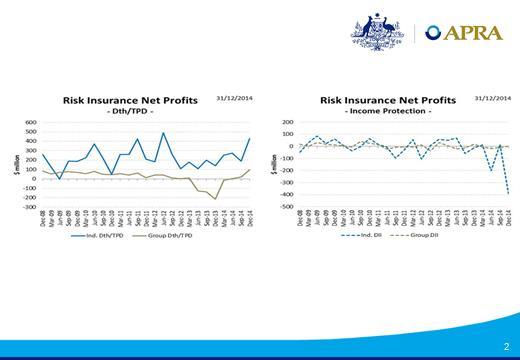

However, in more modern times it has shown susceptibility to periodic bouts of poor financial performance and associated stress on balance sheet strength, and that is of concern to APRA. The recent experience – as shown on these graphs – illustrates one such round of poor performance quite well.

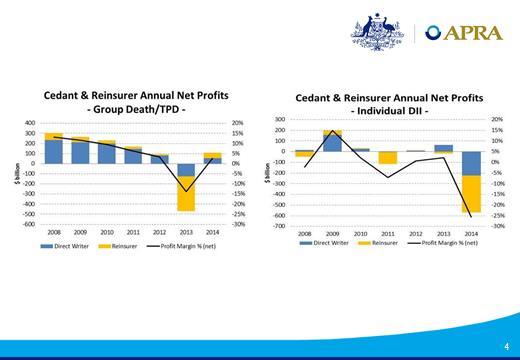

It is worth breaking down this experience into direct and reinsured business. This is what it looks like.

The reinsurers seem to have carried a disproportionate share of the losses. I don’t have time to delve into that today but it begs questions about the nature of the reinsurance arrangements in place and the role reinsurers may have played in the poor overall performance. There also is a question for direct insurers over pricing based on reinsurance arrangements that may not be sustainable, with consequential impact on premium rates. The rest of this discussion focuses on direct business, but much of it is relevant for reinsurers.

This data used in the slides starts in 2008, which coincides with the GFC of course, but it would be quite inappropriate to dismiss the poor performance simply as a function of the economic cycle, which is an argument we sometimes hear.

Note the persistency of the poor performance, which calls into question the industry’s ability or intent to address the causes of the problem. I don’t have data to show you, but the industry has seen previous periods of poor profitability (particularly with disability business), and this suggests the industry may not learn from its own past mistakes.

Today I want to explore some of the reasons for this propensity for performance lapses and to propose a shift in thinking about management and governance of life risk business, aimed at more stable and sustainable outcomes, in a rapidly changing world.

However, the focus of my talk today is on practices that threaten the industry’s long term stability and sustainability and how they might be improved. So some of my comments are critical, but this is not intended to diminish the many positive attributes of the life industry and the considerable value in the innovative market developments we have seen over the years. Indeed a vibrant and competitive industry is in everyone’s long term interests. Some of the poor practices mentioned later are being addressed by some companies, but there is much that still can be done.

I want to stress that in no way am I arguing that the ideas put forward today are the answer to the challenges faced by the industry. Rather, they are intended to challenge, and to provoke significant change in thinking about management and governance of life risk business.

The industry and its products

Let’s start with some observations on the life industry and its products.

For many years, there were only a small number of products, and their features, terms and conditions were relatively unchanging. There then was a proliferation of product types. Over the last couple of decades, there has been a steady increase in the focus on pure life risk business – term, disability income, trauma and the like. This business has shown strong and consistent growth, and there are a number of companies that specialise in it – retail and/or group.

It is this business to which I want to pay attention today. It has been the major source of the industry’s problems in recent years.

Note for reader: Attachment A has more background on the industry, including a little history.

The marketplace

Let me now make some observations about market behaviour.

Success in distribution of life insurance has always been a critical part of the business model, as evidenced by the old adage that life insurance is sold and not bought. That may or may not be less true today, but sales and growth in size remain core to the industry’s culture. This culture has sometimes overwhelmed the fundamentals of sound insurance management and continues to have a strong influence today.

With the old mutuals in particular, distribution used to be dominated by tied agents. Now, the ties have been loosened so that agents or advisers are aligned to an insurer but have considerable freedom to sell products of other insurers. Further, independent advisers play a much greater role in the market, and direct distribution has gathered an increasing share of retail business. This change in distribution has driven life insurer behaviour, as they have competed for the support of the advisers and/or sought alternatives to reduce reliance on adviser favour.

Adviser commission terms play an important role here. This is currently subject to considered review by the industry, and so I won’t make any further comment on this today.

Partly as a result of the focus on sales and distribution, there are a number of practices that APRA has observed in the market which arguably do not meet standards of fundamental good practice in insurance management, and that very likely contribute to poor performance over time. These are summarised on the slide.

They include product features added at no cost or with little analysis of impact; definitions that are open to interpretation or prone to obsolescence; various basic problems with underwriting and claims management; and a lack of information to support proper analysis. Note to reader: More details are given in Attachment B.

The advent of questionable practices often has been driven by the desire to score well in product ratings (by “ratings houses”) in a bid to attract business from advisers. Not only can this undermine sound insurance management, but it often will result in features that are not necessarily needed or wanted (or understood or appreciated) by the customer.

There also has been the development of directly marketed (e.g. through TV advertisement) business. Advertising has largely driven the growth in this business, and experience has been poor in a number of respects [1], though in more recent times the industry has taken steps to address some of the poorer practices which contributed to this.

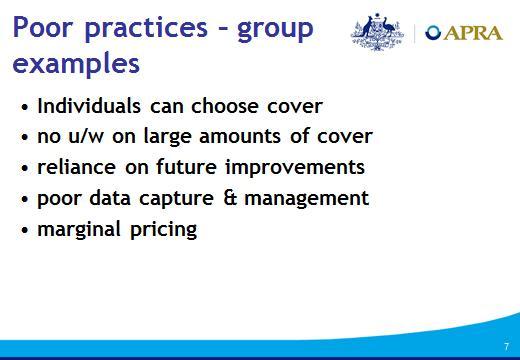

The practices evident in group insurance have been no better than in retail. The market for group insurance has grown enormously over the years, mainly due to the success of the industry superannuation fund movement, and so the prizes in terms of business volumes are great. In turn, the market power of the large industry funds is considerable, and over the years this power has been wielded to great effect on premium rates and product features.

Some examples of poor practices seen in the group insurance market are summarised on the slide. They include overly generous underwriting concessions for individuals; reliance on anticipated future improvements in mortality experience; poor data capture and management (so analysis is compromised); and marginal pricing (which has pros and cons). While there has been solid progress on addressing some of these issues, much remains to be done. Note to reader: More details are given in Attachment B (below).

These practices have been observed in a group risk market which has some inherent challenges. For example, some individual plans are extremely large, which can influence behaviour and practices in tenders by both incumbent and prospective insurers because of the consequences of winning or losing the business. As another example, there is a lack of industry experience investigations and research to provide objective benchmarks and good practices, and to help identify trends.

Society

Overlaid on all of this are changes in society generally. There are shifts in attitudes and behaviours under way that have had and likely will continue to have a profound impact on life industry experience.

Here are some examples:

- changes to brand loyalty and a willingness or even expectation to regularly and readily change product supplier;

- heightened awareness of death and disablement benefits provided through a superannuation fund;

- increasing litigiousness;

- a drive by the legal profession to generate business by advertising assistance with claims, developing alliances with various support groups etc.;

- partly due to that point, an increased willingness to lodge claims years after the event, which means TPD claims have become increasingly long-tailed;

- changing attitudes to mental health, in that there is a much increased awareness of and a greater willingness to acknowledge mental health problems;

- increased workforce mobility (changing employer/occupation class) and a move from full-time to permanent part-time and casual work; and

- advances in medicine, so that some benefit payments are a financial windfall.

No doubt there are many more.

Risk and uncertainty

Before going further, let me briefly discuss risk and uncertainty in a general sense. (For clarity, I am now talking about risk with its general meaning, not risk insurance business).

Some risks are relatively well understood, with recorded experience and lots of data to draw on, and so are quantifiable with some accuracy.

Other risks are only partly understood or may not be known at all, and thus may be impossible to quantify, or any quantification may be subject to significant uncertainty. This might be because of lack of historical data or due to changes in society (see my earlier comments).

Let’s now consider the life risk business in that context.

Mortality rates tend to be reasonably stable, and so death insurance risk can be quite accurately quantified [2]. Note however that some of the industry practices I mentioned earlier – in both retail and group – have introduced more uncertainty in the future experience than has previously been the case.

Disability risk is more problematic. There are many factors that have and will influence disability claims experience – some self-imposed by the industry and some as a result of changes in society (again see earlier comments). The impacts of many of these are difficult to assess and quantify. In other words, uncertainty with respect to disability experience has increased markedly.

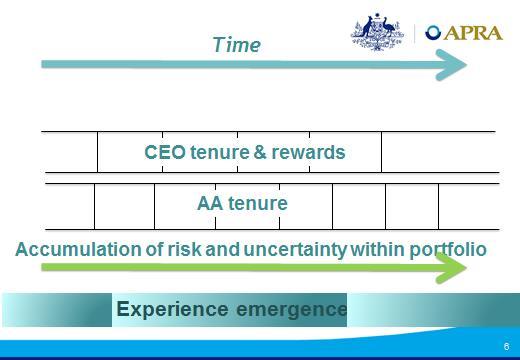

Accumulation of risk and uncertainty

If one then considers a typical portfolio of life risk business exposed to the myriad of influences as I have just set them out, its inherent risk and uncertainty accumulates over time. This aggregation of risk and uncertainty may not be well understood or even identified, because of the piecemeal way that it comes together over a lengthy period of time.

So unless actively addressed in management and governance this accumulation of risk and uncertainty is likely to continue, eating away at sustainability like a rat gnawing on an electric cable.

In other words, the quality of the insurance portfolio of an insurer in this position will probably steadily deteriorate, with a consequent effect on claims, and then reserving and pricing.

From time to time, individual insurers and/or the industry are jolted by experience and make changes to pricing, products or practice that attempt to correct the position (or perhaps address the symptoms), and the customers pay the price in higher and more volatile premiums. This may sound familiar to you.

Other forces at work

There are other features of the contemporary industry that make it difficult to manage an accumulation of risk and uncertainty in the portfolio.

Senior management tenure tends to be shorter than it once was. This in turn means that the underlying causes of poor experience often straddle the time in the job of more than one CEO (and other senior managers). Appointed Actuary tenure is also much shorter that it once was [3].

Corporate memory is also impacted by this turnover, and this is exacerbated by risk business specialists moving to another insurer before the fruits of their work have matured. True underlying experience (particularly when it is poor) can take years to emerge - and then sometimes shows itself quickly as the inadequacy of reserving and pricing is realised and corrected.

There thus is a mismatch between senior management and AA incumbency on the one hand and experience emergence on the other – that is, the management team in place when (poor) experience emerges is often different to the management team that made the many and various decisions that led to that performance.

It is true that remuneration for senior management has changed since the GFC [4], and in particular, there is greater deferral of rewards and even the prospect of claw-backs of past awards. However these deferral periods can be much shorter than the lengthy period over which poor experience can emerge in a life insurance portfolio. Thus, current remuneration arrangements don’t necessarily drive the right behaviour.

So now we have a picture which is something like this:

What does all of this mean?

From the overview of the industry I have just given, with the many and varied forces at work and associated risks and uncertainties, a proposition can be made that the life insurance system has become more complex, and it has greater inherent riskiness and uncertainty than was the case, say, twenty-five years ago.

Arguably, we have seen the consequences of this in recent years with the poor claims and financial experience, and the volatility in premium rates.

An argument can be made that absent a change in approach to the management and governance of life risk insurance, we can expect ongoing intermittent periods of poor experience over and above those purely generated by economic cycles.

However, we need not, and should not, accept that position.

What should be done?

Here is one proposal. I stress this is a proposal intended to challenge thinking. It is not put forward as the only way to manage and govern life risk business.

The proposal

Let’s start with a set of drivers for management that support a healthy portfolio of risk business.

The first issue is the mandate. Rather than goals built around relatively short term and incomplete measures of portfolio performance, such as profit or growth, an objective could be set to drive the long term health of the portfolio of risk business. So, for example, consider a primary mandate for senior management along these lines:

- to maintain a healthy life insurance portfolio over the long term (i.e. a term which goes well beyond the tenure of incumbent management); and

- to hand that portfolio over to their successor in better health than when they inherited it.

A healthy life insurance portfolio should deliver a relatively stable, sustainable return on capital, at a rate that meets shareholder hurdles.

This primary mandate does not preclude other management objectives (such as growth or market share targets), but it would mean that any such other objectives should not compromise the primary one above.

One might quibble over the details of this, but it is hard to argue with its essence. However, this philosophy would not seem to be at all consistent with the way many companies in the industry are actually managed.

How might an insurer go about maintaining such a portfolio?

Well, there are a number of matters to be addressed as shown on this slide.

Some of these are just about basic good practice. The point is however, that we see these basics managed poorly in a number of companies.

Other points are different to traditional thinking and are more of a challenge to understand and accept.

Let me now comment on each of them.

The basics

Data

Comprehensive and accurate data should be collected and maintained, and subject to timely analysis, to facilitate effective management of the portfolio and to measure its performance. This might seem a statement of the obvious, but many insurers would find it a challenge [5]. To make matters worse, reinsurers can have fewer data than the direct insurers.For consideration by insurers: Do an honest assessment ofThen form a view of the changes needed for the insurer to properly manage a portfolio of life risk insurance and maintain its long term health.

- the state of your records and of the ability of your systems to capture all information needed; and

- the adequacy of analysis currently undertaken, and the capabilities available to do that analysis.

Underwriting

Underwriting standards should be technically sound and be supported by strong underwriting capabilities and disciplined compliance.

This sounds like motherhood and apple pie, and it is. However, as explained earlier we observe practices in the market which are quite deficient.

For consideration by insurers: Have an independent assessment (e.g. by a parent company, a third-party reinsurer or a consultant) of your underwriting standards, an audit of compliance with those standards, and a review of underwriting skills.

Claims management capabilities

The claims management function should be skilled, properly trained and adequately resourced. The claims management process should treat customers fairly, but also minimise the negative impact of any event giving rise to a claim.The net result should be that within the terms of the policy only fair claims are paid and income payments do not continue beyond what is fair and reasonable.Again, there should be absolutely no surprise in this statement. However, we find that almost every insurer is embarking on some new ‘claims initiative’ that will improve claims experience, suggesting that past practices were inadequate. And this has happened before!

For consideration by insurers: Have an independent assessment (e.g. by a third-party reinsurer or a consultant) of your claims management capabilities and resourcing. Ensure that there is appropriate planning for expected claims volumes based on growth in business volumes over the previous 5 to 10 years and trends in claim activity.

Product

In most industries, it would be axiomatic that products have features that customers desire and want. As explained earlier, that often is not the case in the life industry.Products should have features that are driven by customer demand and need. Policy terms should be clear. Definitions should allow limited room for interpretation, and be designed to cope with future advances in medical treatment.There should be minimal scope for financial windfalls for policyholders.

For consideration by insurers: Test existing customers on their ability to understand their products and have them examine the perceived value of each feature.

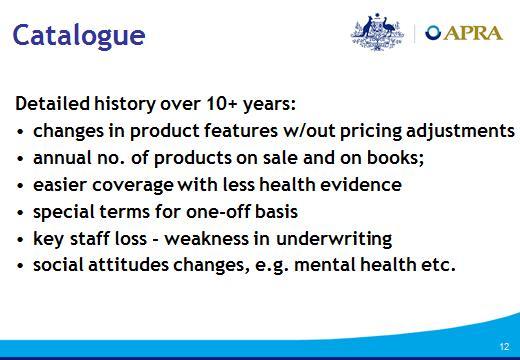

Accumulation of risk and uncertainty

There should be a capacity to monitor and assess the accumulation of risk and uncertainty in the portfolio that may have occurred over time for the reasons mentioned earlier.

One way of doing this would be to maintain a catalogue of matters that may contribute over time to such aggregation of risk and uncertainty in the portfolio.

For example, detailed history over at least 10 years of “free” product changes; termination of policies as a results of premium increases; changes in underwriting standards; weaknesses in underwriting capabilities; and changes in social attitudes (e.g. to mental health, or to claim propensity, or to willingness to change suppliers) and other external forces that could have an impact on experience (e.g. epidemics). Note for reader: Attachment C has more detail.

This catalogue would be considered in any significant pricing or reserving decision, and whenever changes were contemplated in product features or underwriting or claims management standards. Any decisions would then be made within the context captured in the catalogue, and in particular the assessment of the accumulated risk and uncertainty in the portfolio.

For consideration by insurers: Produce such a catalogue. Require management to include in proposals to the board matters in the catalogue they consider relevant to the case in hand, explaining what specific allowance had been made in their proposals for the accumulated risk and uncertainty in the portfolio.

Risk appetite

We have long argued that a clearly articulated risk appetite is fundamentally important to sound risk management of an insurance company. However, life insurer risk appetite statements (RASs) are often not clear in setting out what are acceptable bounds for insurance risk. Too often we see statements to the effect that the company is in business to write insurance business, and therefore it has considerable appetite for insurance risk. This is of little help in guiding the business.It would be better that the RAS and supporting, more detailed risk tolerances set expectations with respect not to aggregate insurance risk but to the quality of insurance risk.This might have regard to, in respect of a particular business line, the level of uncertainty in pricing, the anticipated volatility of claims experience, the capital intensiveness relative to other lines, the insurer’s experience and capabilities in the business line, the availability and quality of data, the degree of reinsurance support available, the implications for customer reaction and market response of using future re-pricing as a risk mitigant, and so on.For operational purposes, this would then be translated into underwriting and claims procedures, and into product design and pricing frameworks.

For consideration by insurers: Do your RAS and supporting risk tolerances provide clear guidance for the quality of insurance risk and are there robust procedures in place that translate the RAS into operational frameworks? Do they make clear the limits on the volumes of particular products that can be accepted and the requirements relating to reinsurance support or other risk mitigation features?

Risk management framework

It is one thing to have a nicely crafted risk appetite statement; it is another to have disciplines in place to ensure that all material risks are robustly and systematically managed. A strong risk management framework[6] is needed to achieve this.For consideration by insurers: Are you satisfied that the risk management framework is comprehensive and effective in dealing with the risks associated with the long term health of a life risk portfolio?

Risk culture

To be effective, the risk management framework needs to be supported by an appropriate risk culture. A truly strong risk culture can be a powerful tool in moderating the sort of behaviours and decisions discussed earlier that might undermine the sound management of a portfolio of life risk business.For consideration by insurers: How might the board satisfy itself that the risk culture is appropriate for sound long term health of the life risk portfolio?

Reporting and monitoring – the dashboard

There are many indicators of a healthy body. Similarly, there should be multiple indicators of the health of a life risk portfolio.Management reporting for a life risk portfolio should be rich in information and provide insights into the true underlying performance and trends. It should include an assessment of the overall health of the portfolio using multiple measures, including a number not usually considered.

The dashboard might include short term and long term profitability, broken down by product and product feature/definition, by policy duration and by applicable underwriting conditions; plus an assessment of the uncertainty of the above profit measures, and a judgement of the underlying profit and trend for the portfolio.It might also include assessments of complexity of products, capability of products to cope with changing market conditions; quality of data held; underwriting capabilities; claims management capabilities; and risk culture.Lastly, there should be view on compliance with the risk appetite. Note for reader: Attachment D has more detail.

For consideration by insurers: Does your current management reporting give sufficient insights into the long term performance and health of the life risk portfolio?

Remuneration

Remuneration arrangements should heavily support the primary mandate to look after the long term health of the portfolio. This would mean a significant shift from commonly used performance measures.To the extent that measures of current profitability are used for remuneration purposes, there should be an adjustment for the assessment of uncertainty in the results – in effect the reward should be risk-adjusted.

For consideration by insurers: Does the current remuneration system give sufficient weight to longer term performance, and does it emphasise performance based on the health of the portfolio as a whole? Is remuneration sufficiently adjusted for uncertainty in the results?

Governance

Under this model of long term portfolio health, strong and effective governance overseeing all of the above is critical. Governance can bridge short management tenures, and can ensure an objective focus on long term portfolio health through performance management and reporting, risk-based remuneration, robust risk management and development of an appropriate risk culture.The board could also ensure there is a sustainability filter on all major decisions – as a practical expedient, it could ensure that there is a section on sustainability in all board papers, perhaps built around questions like these:

For consideration by boards: Are you satisfied that your governance gives appropriate weight to the long term health and performance of the life risk portfolio?The importance of governance and its potential to oversee the long term health and performance looks a little like this:

- What are the risks of this being a wrong decision?

- What are the implications of it being wrong?

- What deficiencies are there that might hinder a proper assessment of the risks?

- What deficiencies are there that might hinder an effective assessment of experience in future (e.g. a lack of granularity of data held about underwriting conditions at the time of policy implementation)?

- How long might it take for the true performance to become apparent?

Conclusion

And that is an appropriate point to finish – on the absolute criticality of effective governance, not just by the board, but within the business – to the long term health of the life risk portfolio.

I stress again that the ideas put forward today are meant to provoke and challenge established thinking. They are not intended to be the definitive approach to the management of life risk business.

I hope what I have said today helps stimulate change for the good of the industry.

Attachment A: The industry and its products

For much of its history, a great majority of the life insurance industry was made up of mutual societies, and a high proportion of cover (mainly death only) was provided through participating policies. By their very nature, participating policies provide a degree of protection to the company, with adverse experience able to be effectively managed through the bonus allocation system. Over the last twenty-five or so years, however, most companies have demutualised, the industry is now dominated by for-profit companies with share capital to service. During the same period, participating business ceased being sold and thus in-force participating business has dwindled so that now it is only a small proportion of the overall book - though in some cases it is still a material source of profit and risk. At the same time, the nature of the cover has changed, so that there is much greater exposure to contingencies which involve judgement and have longer tails.

The industry now is made up of 28 life companies (plus 12 friendly societies) with a mix of business models. Indeed the industry is quite heterogeneous in this respect.

Here is one way of looking at the industry:

- Six medium to large insurers selling a diversified but similar range of product types. These insurers are active in the life risk business market (individual and, to varying degrees, group) have substantial portfolios of investment-linked business, and a book of legacy business.

- A number of smaller insurers, which tend to be focused on risk insurance – including in some cases, group insurance on a significant scale.

- One insurer largely focused on annuity business.

- Seven reinsurers (all subsidiaries of international groups)

There is little regular-premium, non-superannuation savings business now written, and long term capital guarantees for new policies are not at all common (with the exception of annuity business, which is growing).

In some cases, investment-linked business is still being written in significant volumes – mainly as retail or corporate superannuation business. As an aside, this business has not been a major source of losses or other significant prudential concerns (apart from unit pricing problems a few years ago).

For many years, products (their features, terms and conditions) were relatively unchanging. Over the last few decades however, competition has driven the industry to make numerous changes to product features and pricing.

For many years, there were only a small number of products and their features, terms and conditions were relatively unchanging. There then was a proliferation of product types, but over the last couple of decades, there has been a steady increase in the focus on pure life risk business – term, disability income, trauma and the like. This business has shown strong and consistent growth.

For life risk business, while policy terms can be set for many years, premiums most commonly step annually and premium rate guarantees tend to be limited to relatively short terms7.

Attachment B: Examples of poor industry practices

Examples of practices that APRA has observed which arguably do not meet standards of fundamental good practice in insurance management are set out below. Some companies are addressing some of these practices, particularly in group business, but much remains to be done.

Retail life risk business

- Numerous product features [8] which individually may appear to be relatively trivial (and may be difficult to cost because of lack of data etc.) added to a product [9] over time with little or no change in pricing along the way;

- product features with pricing that is not supported by rigorous analysis (perhaps because of lack of data or lack of understanding of likely claims rates). Sometimes this is accompanied by an attitude that you can always reprice later if experience turns out to be worse than expected (because premium rates are not guaranteed), without consideration for the impact on lapse rates of increasing premium rates at a later date;

- basic disablement and trauma definitions that are quite open to interpretation (even if they have worked effectively in the past) because of the broad way they are worded;

- disablement and trauma definitions that cover ailments that are inherently difficult to assess with confidence, or that are prone to obsolescence;

- disablement definitions that covers frailties common to blue collar workers simply as a result of wear and tear as they age;

- underwriting processes and conditions that have been simplified, relaxed or compromised in some way [10] in a bid to win adviser support or reduce costs, exacerbated at times by poor technical underwriting skills;

- inadequate resourcing or skills needed for sound claims management (including what is needed to cater for changing social attitudes/behaviour and market conditions);

- the payment of benefits without admission of liability or other ex-gratia amounts to curry adviser favour, avoid negative media attention or maintain good relationships with trustees or other key players;

- complex products that are difficult to understand and to administer; and

- inadequate detail held and analysis undertaken to understand the level of exposure to risk and trends in underlying experience [11].

Group life risk business

- underwriting concessions which allow individual members significant discretion as to whether and how much cover is taken;

- large amounts of cover provided with no underwriting checks or other conditions imposed at all;

- reliance in pricing and reserving on anticipated future improvements in mortality experience;

- poor data capture and management, so that experience is difficult to analyse with sufficient granularity - particularly in relation to new features – and pricing and reserving then are compromised [12];

- inadequate capture of data and experience from previous insurer resulting in poor allowance for claims development;

- pricing for large new contracts on a marginal basis (which has pros and cons).

Attachment C: Accumulation of risk and uncertainty – Catalogue example

Detailed history over at least 10 years of:

- changes in product features - particularly a series of changes - introduced without soundly-based, explicit adjustments to pricing; this includes variations in definitions of disability and other conditions;

- changes in premium rates and related impacts on lapse rates – in particular healthy lives terminating policies and less healthy maintaining cover;

- number of different products currently on sale and on the books, for each of the last 10 years;

- changes in underwriting standards that have made it easier to get cover with less evidence of good health;

- special terms that may have been granted on a one-off basis – for example for a group insurance policy;

- weaknesses in underwriting capabilities (perhaps because, for example, the business has grown quickly or because of a loss of key staff); and

- changes in social attitudes (e.g. to mental health, or to claim propensity, or to propensity to change suppliers) and other external forces that could have an impact on experience (e.g. epidemics).

Attachment D: Dashboard

The dashboard might include:

- Short term and long term profitability, including trends and volatility, with explanation of movement. This should be broken down by product and product feature/definition. It should also include an analysis of profitability by policy duration to highlight anti-selection effects (healthy policyholders terminating), and according to applicable underwriting conditions;

- An assessment of the uncertainty of the above profit measures, and a judgement of the underlying profit and trend for the portfolio;

- An assessment of complexity of products, both currently being sold and older products on the books, and how this assessment has moved over the last 10 years; This assessment might be based on length of policy document, and by number of features that score in ratings;

- An assessment of capability of products to cope with changing market conditions;

- Average size of policy over each of the last 10 years with explanatory commentary;

- An assessment of quality of data held;

- An assessment of current underwriting capabilities over each of the last 10 years;

- An assessment of current claims management capabilities over each of the last 10 years;

- An assessment of risk culture over each of the last 10 years;

- An assessment of compliance with the risk appetite for insurance risk over each of the last 10 years.

Footnotes

- e.g. high lapse rates, and low levels of customer satisfaction.

- It is worth noting though that secular trends such as ongoing improvements in mortality rates can boost profits but also can cause long term uncertainty and so there can be challenges in quantifying longevity risk.

- At the time of writing, the Actuaries Institute is doing further analysis to provide deeper insights into this experience. Various recommendations are expected to flow from this.

- See Prudential Standard CPS 510

- For example, claims management systems often do not contain the information needed to support a thorough analysis of claims experience. This can also impede industry-wide analysis (which incidentally, is often not timely).

- APRA sets out requirements for a risk management framework in CPS 220.

- For individual business, changes to rates must apply to at least a particular grouping within the whole portfolio of like business (males, age 46, rated as blue collar, etc.) and not to individual policies.

- For example, additional conditions covered under trauma policies.

- Often added to existing policies as well as future policies for administrative expediency.

- e.g. generous financial underwriting of agreed value cover for disability income insurance, and income replacement ratio not applied to additional benefits.

- For example:

- indication if a policy was underwritten at outset or was a replacement / transfer / continuation option / buy-back;

- the proportion of the premium relating to each benefit;

- identification of the benefit to which a payment is related;

- indication of an underwriting loading being waived.

- Refer to the discussion note from the Actuaries Institute Life Insurance and Wealth Management Practice Committee on IBNR for some insights.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.