APRA Executive Board Member, Margaret Cole - speech to the Financial Services Council webinar

Come together: overcoming super's sustainability challenge

Good morning, and thank you for inviting me to deliver some reflections on the state of the superannuation industry.

Throughout my career, I have tried to follow the advice given to me by a colleague when I first qualified and started to practise as a litigation lawyer. He said I should never be surprised. This doesn’t mean I’ve never been surprised in a professional capacity: I have spent the varied chapters of my career being interested and concerned, fascinated and sometimes downright perplexed through major events such as the global financial crisis, Brexit and now COVID-19. But I was counselled early on never to admit to it – and definitely not in writing.

Yet in bold defiance of this instinct that has served me well over many decades, I confess that I have been surprised by a number of things about Australia’s superannuation industry since commencing with APRA on the first of July this year. Even more audaciously, this speech is being published on the APRA website, meaning my admissions are now in writing too!

Some of the things that have piqued my interest have been of the pleasant variety. I have found myself working with passionate and committed people at APRA, within Government, at peer regulators and the funds themselves; people who are genuinely committed to delivering the best outcomes they can for members. The sheer scale of this industry is impressive: a $3.3 trillion value, equal to 160 per cent of GDP as at 30 June 2021. In line with Treasury’s 2021 Intergenerational Report, this is forecast to grow to around 244 per cent of GDP by 2061, with almost three-quarters of funds under management expected to be held in the accumulation phase. Seeing total superannuation assets grow last financial year by 14.7 per cent in the midst of a pandemic has also been a happy revelation. It’s a subject of relevance to the lives of every working Australian, those in retirement and those yet to join the workforce, and shows super is capable of being a powerful force for good in society and for the Australian economy.

At the same time, while not all members are as engaged as they should be, there is intense political and media interest in super. This simply doesn’t exist in any comparable way in the UK. I have found an industry starkly focused on distinctions between retail, industry, corporate and public sector funds; with sharp and often fiercely contested differences in views about the best model, laws, regulations and practices needed to protect members’ interests. I’ve also been amazed by the extraordinary number of funds and investment options available to members. In a highly competitive and scrutinised industry where economies of scale play such a crucial role in determining performance, this apparent reluctance to pursue beneficial fund consolidation and product rationalisation is puzzling.

I have also observed the pace of change over recent years; not only the number of changes, but also their significance, whether it be the Government’s Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) reforms, the introduction of opt-in insurance in super for younger members and those with low balances, or APRA’s first MySuper Performance Heatmap and Superannuation Data Transformation. The sheer scale and weight of reform brings its own challenges and opportunities – not just for risk and compliance professionals (in demand these days like we would never have imagined) but for CEOs and boards facing the responsibilities of leadership in interesting times.

For all the effort by Government, regulators and others to lift industry standards and improve member outcomes, it’s disappointing to see persistent underperformance among a minority of funds. That underperformance isn’t confined to any one sector; there are outstanding performers and also-rans across every type of ownership and control model. However, given that the FSC represents the retail super sector, I have tailored my remarks today to concentrate on that part of the industry.

With 30 per cent of total assets held by APRA-regulated funds sitting in the retail sector, it’s vital these products deliver the best possible outcomes to members. Yet retail funds have historically been able to avoid holistic scrutiny thanks to gaps in APRA’s data collection, and a bewildering array of products and options that makes comparisons difficult. That era is now at an end, as APRA and Government shine a progressively brighter spotlight on the choice products that are dominated by retail funds. This will culminate in the first choice performance test in the middle of next year. For funds struggling with poor performance or lack of scale, these changes will only increase current sustainability pressures. But with APRA’s first choice product heatmap later this year to show which products are underperforming, no retail trustee that fails the test next year will be able to claim they were surprised.

Shooting for scale

Aside from the Royal Family, the UK’s other obsession is football (and periodic campaigns to bring it “home”).

Growing up in the city of Preston, in England’s north-west, it was hard to escape the aura of our local team, Preston North End FC. With a history dating back to the 1860s, they were a founding club of the original Football League in 1888, and won the very first two League titles. Sadly, the club’s history is rather more glorious that its present. Preston last won a major trophy in 1938.

Not helping Preston, and scores of smaller clubs like them, was the transition that took place in the mid-90s where vast sums of money from television rights flooded into the game, especially for the top clubs competing regularly in Europe. Domestic success led to European riches, which in turn fed into more domestic success by allowing these top clubs to invest in the best players and facilities. The rich got richer and more successful, and the rest struggled to keep in touch. Barring a takeover by a Russian oligarch or Middle Eastern royalty, very few clubs outside a small elite now have any realistic hope of challenging for the Premier League title.

The analogy with super might not seem obvious, but Australia’s superannuation landscape is similarly overwhelmingly dominated by a relatively small number of major players, whose size and influence helps them to build further size and influence, often at the expense of the industry tail.

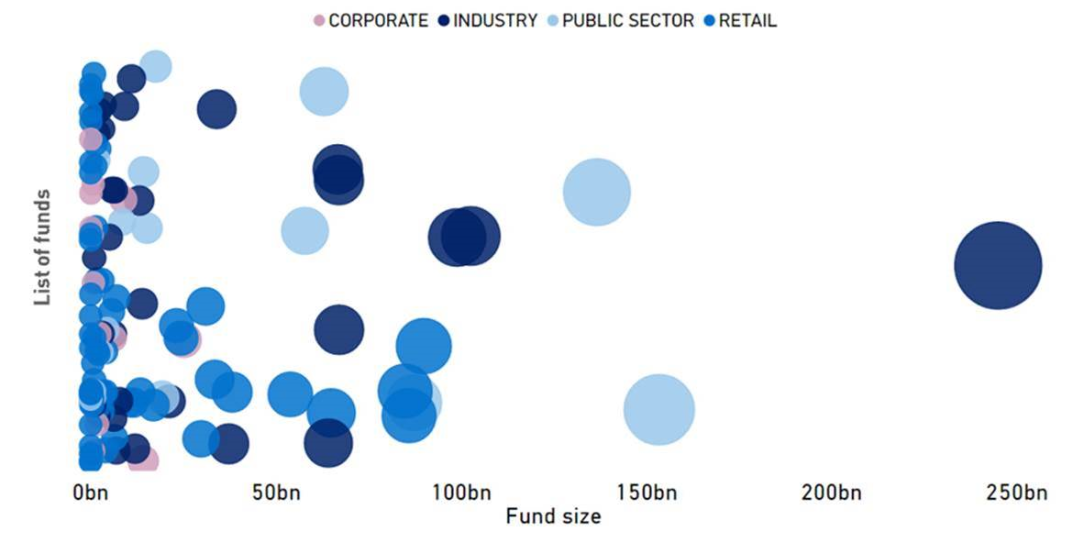

Consider this: at June 30 this year, there were 156 APRA-regulated superannuation funds with more than four members. Four, comprising two industry funds and two public sector funds, each managed assets in excess of $100 billion dollars. Another 13, including five retail funds, managed assets valued between $50 and $100 billion. In aggregate, these 17 funds are responsible for managing 70 per cent of all assets in the APRA-regulated superannuation system.

Then we get to the tail. Eighteen funds manage assets of between 10 and $30 billion, and a shocking number, 116 funds, each have less than $10 billion under management. It’s here in particular where we can see the potential vulnerabilities the retail sector faces in coming years. Of those 116 funds – which together control only 8 per cent of total assets – 78 are retail funds.

Breakdown of APRA-regulated superannuation funds by size and type

Size is not the sole determinant of performance. If it were, some of the 13 MySuper products that failed the recent performance test would have done markedly better than they did. But it is absolutely a key factor influencing not only member outcomes, but also the sustainability of outcomes into the future. Increased scale enables trustees to spread fees and costs over a larger membership base, and access higher earning investments in unlisted assets, such as major infrastructure projects. APRA doesn’t have a rigid view of what size a funds needs to be to compete with the emerging cohort of so-called “mega-funds”, but we broadly agree with industry sentiment that any fund with less than $30 billion may struggle – and any fund with less than $10 billion, without some other redeeming feature, will definitely struggle to stay competitive into the future.

The challenges many retail funds face will become evident in coming weeks when we publish the findings of APRA’s new information paper analysing the choice sector in preparation for our first Choice Product Heatmap in December: substantially higher average administration fees than for MySuper products; far greater variation in performance; and significantly higher levels of underperformance. While that analysis covers choice products in all industry sectors, including industry funds, the majority of products and options analysed were operated by retail funds.

The performance and sustainability challenges facing the industry’s long tail aren’t about to get any easier. If anything, they are likely to accelerate, as the mega-funds use their financial strength and higher profile to grow further by attracting new members, and fund stapling breaks the traditional nexus between employers and default super funds. Greater transparency, through APRA’s heatmaps and expanded data collection, and the YFYS reforms, will make it easier than ever before for members to identify the poor performers, and move their money elsewhere. The funds they move to will often be those brands they are most familiar with, further bolstering the influence of the largest funds.

These trends are already evident. In the six weeks since APRA published the first MySuper Annual Performance Test results, all but one of the 13 failing funds has seen an overall drop in membership. These drops are marginal to date but any reduction in scale is unhelpful for trustees trying to improve their performance. It’s likely we will see a similar response when the results of the first performance test for choice products are published next August. At the other end of the spectrum, some of the country’s largest super funds are getting around 1000 new members every day, and $500 million of net new cash flow each week. Over a 12-month period, that’s an inflow of $26 billion – greater than the total size of almost 85 per cent of APRA-regulated funds!

Spoilt by choice

Confronted by these irresistible forces, the long-term trickle towards industry consolidation is starting to become a torrent. At the big end of the market, industry giants are pooling resources seeking a further competitive advantage over their major rivals. At the smaller end, pressure from APRA to meet the requirements of a stronger prudential framework, coupled with the threat posed by the new YFYS measures, has prompted a recognition from many trustee boards that they no longer have the size, resources and expertise to protect their members’ best financial interests as a standalone entity.

This recognition may be belated and possibly grudging in some cases, but it’s welcome nonetheless. For all the talk today about the benefits of size, the number of funds and investment options remains so large as to be detrimental to members. Rather than being spoilt for choice, they’re being spoilt by choice.

To begin with, it’s confusing for members, and contributes to them being disengaged from their super rather than grappling with making an informed choice out of more than 140 funds, and as many as 43,000 investment options – equating to one investment option for every 465 Australians over the age of 181! Secondly, it’s inefficient. If scale is an essential component of boosting outcomes to members, the fact that 116 funds together control only 8 per cent of the market is logically a handbrake on optimising those outcomes. Thirdly, it’s unnecessary. Too many funds and investment options are not sufficiently different in terms of their product offerings and features to justify the duplication, confusion and inefficiency.

While relying on organic growth may be an option for a small number of unique funds, I doubt there are many funds, large or small, that don’t understand the trajectory the industry is on, or are not seriously looking at how they can get bigger. While we encourage this, what APRA doesn’t want to see are trustees rushing into poorly planned or sub-optimal mergers. We’ve previously advised trustees against pursuing “bus-stop” mergers, which only take them part of the distance they need to travel. Our view remains that trustees of smaller funds should ideally seek to merge with a larger, better performing partner rather than another small fund – especially one that is also underperforming.

A measure of caution is also needed among larger funds seeking merger partners. Over the past few years, we’ve noticed some larger funds becoming what you might call “serial acquirers”, taking over one smaller fund after another, and often moving on to a new deal before bedding down the previous one. This approach carries risks that the integration of the funds into a single entity is not as efficient as it could be. Given the time and cost involved in executing a merger, it’s vital the benefit to members isn’t squandered through poor execution or deferral of the integration needed to avoid problems down the track.

Retail funds, in particular, should also consider the benefits of consolidating their own product lines. It is common for retail trustees to operate a number of products across multiple funds – noting that each of these individual products is subject to the critical scrutiny of the performance test and APRA’s heatmap. Such an approach may deliver benefits to members in terms of choice of features and investment options, but it works against delivering economies of scale. Consolidating those funds is both an important and necessary way of achieving greater financial and operational efficiencies, which should hopefully flow through to improved outcomes for members.

The ultimate interest

A merger is not the only way a fund can gain scale. The funds benefitting most in terms of member growth following the performance test are those with the biggest brand profiles, which they’ve often acquired through extensive marketing and promotional activities. The risk here is that some trustees of small or underperforming funds might be tempted to think they can therefore market their way to scale and better member outcomes. At a time when scrutiny of trustee expenditure, especially on promotional activities, has never been more intense, forming such a view would be a major own-goal. In the wake of the YFYS reforms, all trustee expenditure, whether conducting an advertising campaign or undertaking a merger, must be in members’ best financial interests.

While promotional activities that raise brand awareness and attract new members might potentially be able to clear that threshold, it is a fallacy that all such expenditure is therefore always in the best financial interests of members.

Earlier this year, APRA conducted a thematic review of expenditure by 12 trustees with a focus on marketing and promotional activities, including industry body advocacy and payments to unions and political parties. Our aim was to examine whether such expenditure was consistent with the former best interests duty and the sole purpose test, and whether it was subject to appropriate governance and oversight. The review found numerous examples of expenditure that fell short of best practice under the old test. Now that the test has been sharpened to best financial interests and the burden of proof reversed, we will use what we have learned to put pressure on trustees to demonstrate their decision-making. They are, after all, spending their members’ money.

Another area we are examining, particularly relevant for this audience, is the payment by retail funds of dividends to their owners. In September, we wrote directly to the trustees of 23 retail super funds requesting information on their dividend payment policies. Specifically, we have sought to determine how they have considered the impact, if any, of the best financial interest duty on their expected future dividend payment practices.

APRA’s position is that there is a place for a variety of ownership and control models in superannuation, and dividend payments are not necessarily contrary to members’ best financial interests. Many retail trustees get considerable benefit from their owners, such as marketing support and investment in essential systems and capabilities, that helps the fund and delivers benefits their members. If these funds are underperforming however, it’s clearly harder for trustees to demonstrate what their members are getting out of the arrangement.

An eye on the future

When Preston North End won the first two Football League titles in the late 1800s, I doubt anyone at the club thought this was as good as it would get for them. Seeing the club 130 years later struggling near the bottom of the second division is a timely reminder that no-one, in any industry, can take their future success and sustainability for granted.

Times change, circumstances evolve, and standing still essentially means going backwards. Continued success requires the ability to adapt, and be ahead of trends, rather than scrambling to catch up. It requires good leadership and investment. Australia’s retail superannuation sector comprises many funds that have long delivered good quality outcomes for their members. But it is also heavily represented among the smallest funds facing the greatest performance and sustainability challenges at a time when the importance of scale, and the consequences for underperformance, have never been greater.

These trends are only likely to accelerate further with the release of the first choice performance test results next August.

Regardless of industry sector, the end goal for every trustee should not be survival; it must be a clear-eyed assessment of what is in their members’ best financial interests. For all funds, but especially for the vast majority managing assets of less than $10 billion, that needs to include urgent, focused consideration of finding a compatible merger partner, or consolidating products, to gain economies of scale, cut costs and lift returns. The publication of

APRA’s super heatmaps in December, including the first choice heatmap, will give another clear indication of which funds are most vulnerable. Those that fail to act swiftly and decisively to remedy underperformance can’t claim to be surprised when they have some explaining to do to their members.

Footnotes

1 On June 30, 2020, there were an estimated 20,037,617 people aged 18 and over in Australia (source: Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.