COVID-19: A real-world test of operational resilience

Operational resilience has been an area of focus for APRA for more than two decades. At a simple level, “operational resilience” refers to how well an organisation can continue providing goods or services when faced with a sudden shock to its normal operating environment – such as COVID-19.

The current pandemic has proven to be a real-world test of the operational resilience of APRA-regulated entities. The introduction of business lockdowns, border closures, and the sudden switch to remote working practices has forced banks, insurers and superannuation licensees to rapidly adjust to new ways of doing business. Changes that might normally unfold over a few years took place in a matter of weeks.

Weaknesses in operational resilience can have both financial and non-financial impacts on entities, and – in the extreme – can undermine their ongoing viability. Just as importantly, ongoing access to financial services, such as banking, insurance and superannuation, is essential to supporting economic activity. For these reasons, operational resilience was one of APRA’s key areas of focus as the threat posed by COVID-19 became apparent.

What is operational resilience?

"Operational resilience" refers to an entity’s ability to withstand and recover from shocks. A shock, in terms of operational resilience, can be defined as an event that threatens the ability of an entity to provide business services, or has disrupted the provision of business services. In the extreme, this includes events which can compromise an entity’s ongoing viability, such as the coronavirus pandemic.

From APRA’s perspective, the core of operational resilience is the ability of regulated entities to continue to deliver business services in the face of potential shocks, including:

- man-made shocks, such as physical and cyber-attacks, IT system outages and third-party supplier failure,

- natural hazards such as fire, flood, severe weather and pandemics, and

- situations and events that require a more strategic response, such as regulatory developments, new competitors with more efficient operating models, risks associated with climate change, and innovative technology solutions.

Operational resilience requires entities to learn from events, whether experienced directly by the entity itself or by others, and to adapt its practices to better deal with such events in the future. Operational resilience, as illustrated in Figure 1 below, is typically facilitated by:

- shock management mechanisms which respond to the full range of plausible shocks that could impact an entity, such as business recovery and contingency planning, and crisis management,

- oversight, decision-making and planning for maintaining the effectiveness of these operational controls, and

- key disciplines for ensuring the design and operating effectiveness of operational controls is in place, such as supplier management, fraud management and change management.

While each mechanism operates separately, entities need to manage all mechanisms as a collective to maintain operational resilience. If the mechanisms are managed in silos and independently of each another, this can undermine operational resilience.

Weathering the COVID-19 storm

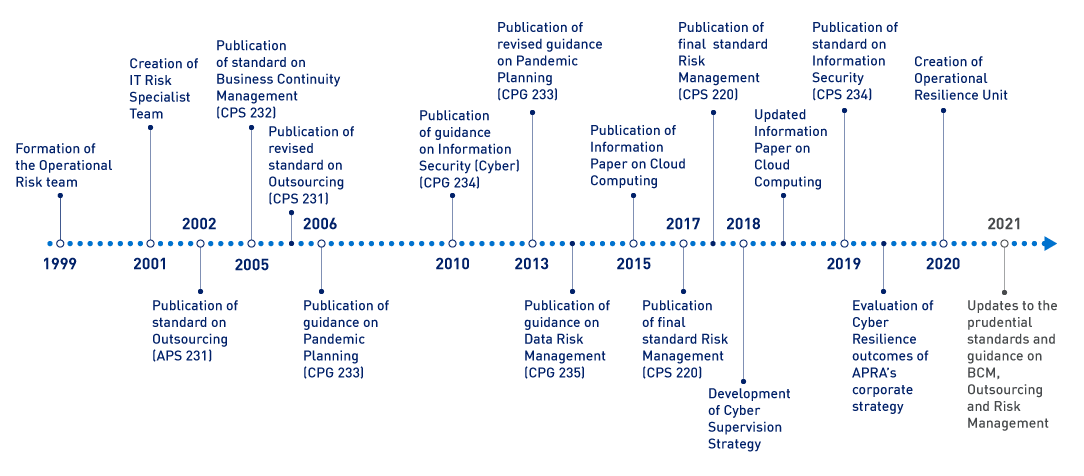

So far, the financial industry has weathered the COVID-19 storm well. Indeed, APRA’s ongoing assessment of operational resilience practices – especially in the areas of risk management, business continuity, management of service providers including cloud computing, data management, and information security (as detailed below in Figure 2) – has resulted in APRA-regulated entities being better positioned to deal with COVID-19 than they otherwise would have been.

At the same time, the pandemic has highlighted opportunities to improve entities’ operational resilience. In Australia, federal and state government health restrictions compelled the majority of entities’ staff to work from home. This introduced new concerns, including the capacity of Virtual Private Networks to support remote working, and the security of information accessed in the home environment.

Some larger entities observed increases in “accidental data breaches”, such as employees sending sensitive data to their personal email to allow for printing. Wide-scale work-from-home issues include staff wellbeing, mental health issues, alcohol abuse and domestic violence. The increased need for Employee Assistance Programs, and the potential for Work, Health and Safety breaches and fines, raise further issues that can affect an entity’s operational resilience.

Overseas lockdowns and changes to business operations meant that some third-party service providers and captive offshore service centres couldn’t meet service level agreements. To accommodate the service provider impacts, entities had to alter their operations, for instance, by some bringing offshore services (such as overseas call centres) back to Australia. This involved diverting staff from other areas and hiring new staff using ad-hoc procedures. Even after COVID-19, it seems unlikely that entities will go back to all of their previous offshoring arrangements, as they look at automating their processing, and reducing their dependency on overseas suppliers.

In addition to the general impact on business operations, activities such as business continuity and disaster recovery testing have also been affected by the pandemic, with entities advising APRA of their inability to meet CPS 232’s (Business Continuity Management) testing requirements. The pandemic’s impacts have not only delayed testing, but have raised challenges in relation to entities’ ability to enact disaster recovery plans from incidents that could take place during this time.

Despite these changes, IT system stability has been at historically high levels, with few major outages reported. One possible explanation is that organisations are temporarily halting changes (known as “change freezes”), which has significantly improved system stability. However, this also introduces a backlog of work that will need to be completed at a later date, which may result in decreases in system stability in the future. In addition, less critical security patches may be deferred by entities, increasing information security vulnerabilities over time if the backlog is not addressed.

Further, the COVID-19 disruption has created new avenues for cyber-attacks. Examples include websites that imitate government or national health websites, and provide false information and pandemic-related aid phishing campaigns.

APRA’s learnings from COVID-19

While the financial industry has managed to maintain essential business services under extremely difficult circumstances, APRA has so far learned some important lessons from the pandemic. These include the need for entities to:

- Use agile risk governance to manage end-to-end processes. Entities need to thoroughly understand their business process/value chain before and after the disruption, to adequately cover the required changes to risk and controls. They also need to be aware of any potential impact on compliance to regulations; have data that is accurate, reliable and can be produced in a timely manner for decision-making; while simultaneously responding to the potential for increased cyber-attacks.

- Consider a broader range of possible/likely disruptions in their business continuity planning, including those seen during COVID-19 relating to overseas lockdowns affecting global offshore providers and the extended work-from-home situation.

- Effectively manage and contingency-plan for critical suppliers, as certain suppliers may not be able to provide the service they were contracted to deliver.

- Assess strategic impact on their operating models, such as shifts towards wholesale branch closures, and the on-shoring of previously offshore processes.

- Implement rapid changes in relation to entities’ workforce planning, such as the need for a flexible workforce to fill critical processes arising from failure of offshore hubs, requiring changes to on-boarding and training while maintaining the work-from-home arrangements.

- Pay attention to system stability. Entities’ measures to improve stability through change freezes and delays to implementation could result in an increased risk of system outages in the future.

- Engage in frequent and effective communication with both internal and external stakeholders to manage and direct health and organisational change, and to manage financial services and impacts on customers, shareholders and other external stakeholders.

- Make quick decisions in relation to customer relief, communicate these consistently and clearly, and adjust supporting systems to reflect business decisions.

Australia’s financial entities are weathering the pandemic well so far. However, COVID-19 is emphasising to APRA and its regulated entities important lessons about the maintenance of sufficient operational resilience, the factors that can undermine that resilience, and the need to consider a variety of plausible shocks. APRA is now applying these lessons to improve its supervision practices to continue to safeguard Australia’s financial system.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.