Governing Superannuation in 2015 and beyond: Facts, Fallacies and the Future

Helen Rowell, Executive Member - AIST Governance Ideas Exchange Forum, Melbourne

Good morning everyone. It is a pleasure to be here, and I’d like to thank the AIST for inviting me to speak to you today.

The topic of governance in the superannuation industry has long been a focus for APRA. In recent months, of course, superannuation governance has had significant focus from a wide range of stakeholders in the context of the consultation on the proposed changes set out in the Trustee Governance Bill1 (the Bill) and APRA’s supporting prudential standards and guidance2.

The role of superannuation as part of the financial services sector, and in delivering outcomes for members in retirement, is critical. Strong governance is therefore essential.

Effective governance has many elements but it starts with the board – its composition and the way it operates. The Government’s proposed requirements provide an ideal catalyst for all boards to reflect on their current and ideal future governance arrangements, review the changes that are needed and take steps to refresh their approach.

APRA’s long-held view is that independent directors play a very important, positive role on boards – not just in superannuation but across all APRA-regulated industries. APRA’s experience, over many years and across all our industries, is that having at least some independent directors on boards supports sound governance outcomes. Independent directors broaden the skills and capabilities that can be brought to the board table, and improve decision-making by bringing an objective perspective to issues the board considers. They are also well placed to hold other directors accountable for their conduct, particularly in relation to conflicts of interest. As outlined in our submissions to the Financial System Inquiry, we consider the diversity of views and experience that independent directors bring supports more robust decision-making by boards.3

APRA’s view on the value independent directors bring appears to be shared by many in the superannuation industry, but it is clear that there are widely divergent views on the proposed changes set out in the Bill. I have been quite disappointed, however, by some of the commentary on the proposed changes and the assertions being made regarding the consequences that may flow from them. And so today I will challenge some of these fallacies and provide APRA’s perspective on the merits of, and need for further changes to superannuation governance. I will also comment on how APRA expects to approach aspects of the proposed changes and some of our expectations of trustees. In doing so, I am making an assumption that the proposals will be passed in their current form; if not, then obviously we would align our approach to fit with the changes, if any, that are made to the SIS Act by the Parliament.

Finally, I will make a few observations on implementation of MySuper ‘scale’ (or ‘member outcomes’) assessments and what else is on APRA’s agenda for the next year or so.

I’d like to start, however, with some context.

The super industry: then and now

The current superannuation landscape is very different to when many funds were established, and to when current governance arrangements for superannuation were introduced.

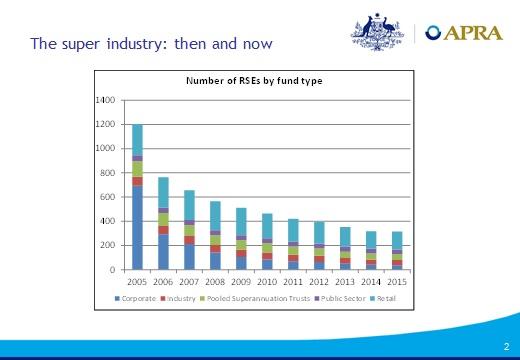

The equal representation model for trustee boards was introduced into law in 1993. It was part of the introduction of the superannuation guarantee (SG) arrangements, under which wage increases were traded-off for superannuation contributions. At that time, the structure of the superannuation industry was vastly different, with many stand-alone corporate funds. Oversight of the newly negotiated superannuation arrangements through equal representation of employer and employee representatives on the trustee boards of these funds was felt to be important.

The superannuation industry has come a long way in the last 22 years. The superannuation guarantee arrangements are well and truly embedded and there has been a dramatic reduction in the number of corporate funds, which are now very much the minority.

Over 80 per cent of the assets of APRA-regulated superannuation funds are in public offer funds with a broad membership base and multiple (and in many cases hundreds or thousands of) employers contributing to the funds.

The industry’s significance, from both a financial system and retirement income policy perspective, continues to increase. Indeed, the size of the industry and individual funds within it has increased significantly in recent years, with more and more funds having total assets comparable to larger deposit taking institutions (ADIs) and insurers. The boards of all ADIs and general and life insurers have been required by APRA’s prudential standards to have a majority of independent directors and an independent chairperson since 2006. And this applies – and, I might add, works well – even when the regulated entities are mutually-owned and not-for-profit. APRA’s view is that, given the size, nature and increasing complexity of the industry, it is appropriate for the governance requirements for the superannuation industry to be more closely aligned with those that apply to banking and insurance. After all, the industry is now an increasingly critical component of the Australian financial system.

The key benefit put forward for the equal representation governance model is ensuring a strong member-focus and opportunities for close proximity to, and deep understanding of member perspectives. This continues to be important – indeed, one could argue having a close relationship with your customers is important for the success of any financial business – but can be achieved under many different governance models.

Another important area of context for the current debate on governance is the vexed issue of performance comparisons, as it is relevant to one of the fallacies that I want to dispel.

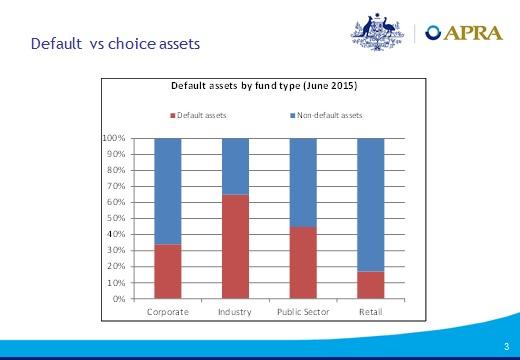

The superannuation industry broadly comprises two types of assets – default assets and choice assets. Choice assets are invested according to the explicit investment strategy selected by the member. Default assets are invested based on the investment strategy set by the trustee, and the member has typically not made a decision to be in the particular fund ("hence the term default member"). Choice assets are more likely to be moved between investment options or between funds at the option of the member than default assets, which are typically quite passive. That has implications for the investment strategy that is appropriate, as a choice fund trustee needs to ensure that the assets are able to be moved should the member wish to do so. It also needs to be borne in mind when making investment performance comparisons.

On a number of occasions in the last few years I have noted that comparisons of investment performance at fund level is not comparing apples with apples. As this slide shows, the proportion of assets in default products vs choice products differs significantly by fund type. Default assets represent 65 per cent of all assets for industry funds, compared to 17 per cent of all assets for retail funds. That means that the investment strategy for 83 per cent of the assets of retail funds is chosen by the members, and the asset allocation – and hence investment performance – at fund level substantially reflects the aggregate of the individual decisions made by the choice members.

A more meaningful, apples with apples, comparison is provided if the investment performance for only default assets (or specific similar choice investment options) is considered. Even then, as I have noted previously, it is most meaningful to focus on performance against objectives (rather than peers) over the long term.

Comparing 'like with like' not 'fund with fund'

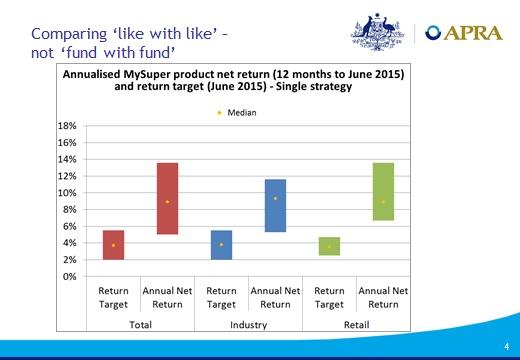

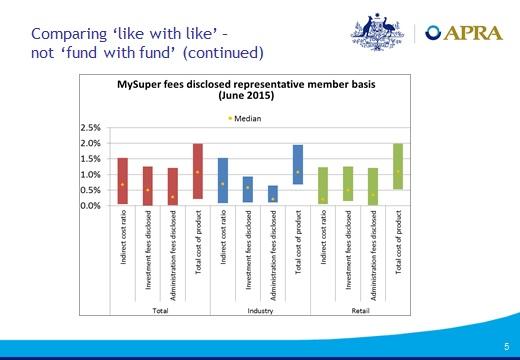

Until recently, data at product or investment option level, rather than fund level, has not been readily available and was not collected by APRA. With the advent of MySuper, however, we are now collecting performance data for these default products. We will also be collecting data for selected choice investment options at the same time that the Government implements the choice dashboard requirements, expected in mid-2016.

Although MySuper data is only available for a relatively short period, it is starting to provide some useful comparative information as indicated by these next two charts. The first shows MySuper return targets and actual returns for the year to June 2015, while the second shows fees and costs disclosed for a representative MySuper member. Across the different industry segments, the median and range of returns for MySuper products is broadly the same, as are the median and range for total fees and costs.

We are always keen to remind everyone that it is long-term performance that counts, so it will be interesting to see what this data shows as MySuper products evolve over the medium to long term. Ideally, however, the focus of stakeholders will be on ensuring that all MySuper products are meeting their objectives and delivering sound outcomes for their members and that the issue of which segment of the industry is providing the product is not seen as being relevant.

Let me turn now to some of the fallacies in the current governance debate that I would like to try and dispel.

FALLACY #1: Independent directors will force fund structure and culture to change

If passed, the proposed requirements of the Bill, supported by APRA’s prudential standards, will require trustees to ensure that the requirements in relation to the minimum proportion of independent directors are met, whilst ensuring that the board as a whole continues to have the skills and capabilities needed to ensure sound governance and that its obligations to members are met. Boards will need to consider the appropriateness of their current governance structures (including the size and composition of the board) in the context of their current (and future) fund membership, strategy and operations.

Beyond these requirements, however, trustees will have the flexibility to determine the composition of the board. That will enable those trustees that wish to do so to retain an equal representation model for the appointment of the non-independent directors should they feel that continues to be appropriate to their circumstances. APRA’s view is that adding independent directors and maintaining the connection with the membership are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, all trustees are expected to focus on the best interests of members and the governance changes in the Bill are intended to better support that. Furthermore, there are some good examples of this model already working in practice.

Similarly, we would not expect changing the composition of the board to lead to changes to the trustee’s business philosophy or model (such as a move away from not-for-profit status), or to its strategy or business plans. But of course, we do expect all directors to challenge the status quo from time to time, to ensure that the trustee’s philosophy, strategy and business plans remain appropriate and in members best interests.

We would also expect trustee boards to have a good look at their approach to governance in light of the proposed legislative changes. The proposed changes do not impose a one-size-fits-all approach. Rather, they provide a golden opportunity for trustees to reflect on and review the board’s current governance arrangements and determine the governance framework and approach that is most appropriate for them into the future. Boards should be asking themselves:

- Does our board have the right skill sets to best serve member interests given our future strategy and business plans?

- Could our nomination, appointment and removal processes be improved?

- How big should our board be and how will we get to the desired size and composition?

- Are there any constraints or impediments that will need to be addressed?

Once the end goal has been established, the board will need to implement the changes – to the board and its committees, and to supporting governance processes, policies and procedures. The most important step will be choosing directors – and in particular independent directors - who align with the board’s culture and strategy and will ensure the board has the right skills and experience for the future.

Concerns are being raised that there simply aren’t enough independent directors in the marketplace. We struggle to see how this can be the case. We expect boards to look outside their traditional sources of directors; to consider for example, whether their plans to innovate in the digital space could be assisted by bringing in directors from outside the financial services sector, or whether marketing or investment skills are needed. Identify the skill sets, experience and expertise needed by the board to achieve its goals and then look beyond the usual suspects to find directors that have them.

FALLACY #2: Mandating independent directors will lead to underperformance

Some stakeholders have asserted that changing the governance model will adversely impact investment performance.

There is no reason to suggest that adding independent directors should, automatically, change the trustee’s business philosophy, strategy or business plans. Nor must it necessarily alter their investment strategy. The trustee board as a whole has always been, and will continue to be, responsible for setting their investment philosophy and strategies for funds under its oversight. Appointing independent directors that understand and support the board’s underlying strategic objectives will ensure that you can continue to run your investment strategy and operations as you always have (provided, of course, they continue to be in the best interests of members).

FALLACY #3: The reforms only affect industry funds

Some stakeholders have argued that these reforms unfairly target industry funds and will not address governance issues (or are weakening governance requirements) in the retail sector. I disagree - these reforms will ensure sound minimum governance requirements apply across the entire superannuation industry.

At present, there is nothing in the law that requires public offer funds to comply with any board composition requirements. In APRA’s view, all of the industry – including public offer funds - should be subject to minimum requirements for board composition. This is particularly important when, as I noted in my earlier comments on industry structure, over 80 per cent of superannuation assets in the APRA-regulated sector are held in public offer funds.

These reforms will have an impact on all segments of the superannuation industry, including the retail fund sector. The definition of independence in the Bill before parliament goes further than the Financial Services Council’s (FSC’s) governance standard that currently applies to FSC members. There are also a number of retail funds that are not members of the FSC, and so have not implemented the FSC’s governance standard, that will be subject to the proposed requirements.

We therefore expect to see governance practices, and board composition, strengthened across all segments of the superannuation industry as a consequence of the Bill.

Board renewal

The Stronger Super reforms and APRA’s prudential standards have contributed to some strengthening of governance practices of superannuation trustees. APRA’s view, however, is that there is significant room for further improvement in governance practices across the industry.

Some trustee boards are constrained by the existing board composition requirements (whether required by the SIS Act or their governing rules) from being able to appoint directors with the right mix of skills, capabilities and experience to best serve the interests of beneficiaries.

As you would all know, SPS 510 currently requires all trustees to have board renewal policies. Current board composition requirements, however, prevent some boards from implementing effective board nomination, appointment and removal processes to support board renewal, particularly when there is recognition that independent directors have an important role to play in boards having the right mix of skills and experience.

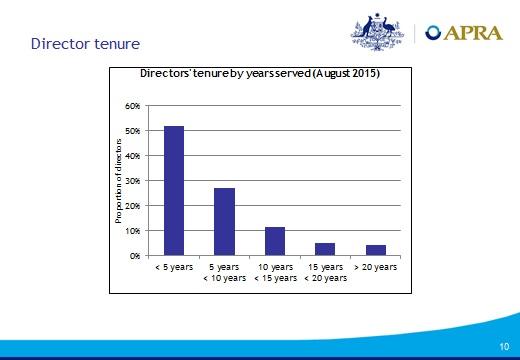

Director tenure

The effect of these constraints is highlighted, for example, by the relatively long tenure of directors on superannuation fund boards – as shown on this slide.

Currently, over 20 per cent of RSE licensee directors have more than 10 years of tenure (over 25 per cent for industry and corporate funds) and a significant number of RSE licensees have directors with more than 20 years (and in some cases more than 30 years) of tenure. In contrast, in the broader corporate community, only 7 per cent of independent directors have tenure longer than 12 years and only 3 per cent have tenure longer than 15 years.4

This is of particular interest and concern to APRA when many board renewal policies that we see - in the superannuation and other industries - put in place maximum tenure periods of three terms, or around 10 years. We would conclude from this data that board renewal policies in the superannuation industry are not as effective in practice as they should be; there will always be exceptions to tenure policies to ensure continuity and experience, but these should be exceptions, not the norm.

There is clearly a balance to be struck between ensuring continuity of experience and appropriate review and renewal of skills and capabilities as the industry and individual funds evolve. However, it is hard to see how the spirit of the prudential standard requirements in relation to board renewal are being met where a substantial proportion of directors on a board have in excess of 10 years’ tenure.

FALLACY #4: APRA’s proposed new powers are unwarranted

For a prudential regulator like APRA, which emphasises prevention of problems rather than after-the-event punishment, our current powers to address governance-related concerns, including issues relating to board composition and fit and proper, are quite limited.

APRA can direct trustees to comply with relevant requirements under section 29EB of the SIS Act (and under proposed section 92, should the legislation pass), but this direction has to follow a contravention of the law; often this comes too late in the process, when damage has been done.

The proposed new APRA powers in the Bill for APRA to make determinations about whether a person is able to exercise independent judgment in performing the role of director are an important element of the reforms. The powers in sections 88 and 90 are necessary to ensure that there is certainty where an individual might have a non-typical relationship with an RSE licensee such that it is unclear whether the individual is ‘independent’. It reflects the practical reality that it is not possible to clearly address in the legislation all situations that may arise in practice; it is essential that APRA is able to respond to unusual circumstances to provide the necessary certainty to industry.

The proposed powers in sections 88 and 90 would enable APRA to make a declaration in relation to a person who meets the legal definition of independence but not the spirit of the legislation (or vice versa) both (a) before an individual is appointed to the board, and (b) without there needing to have been a breach of RSE licensee law, which could cause damage to the interests of beneficiaries.

We have indicated on a number of occasions that we expect to be called on to use the proposed power in section 88 infrequently. This is because the combination of the certainty in the legislative definition, our usual discussions with trustees during our normal supervision processes and additional guidance issued by APRA over time should mean industry can feel confident in appointing persons as independent directors without having to seek confirmation from APRA by way of a determination.

During the transition period, supervisors will regularly discuss with trustees various aspects of their transition plans, including whom they intend to appoint as independent directors. This will also provide opportunities for trustees to seek guidance from us in relation to application of the independence criteria to specific circumstances that may arise in implementing their transition plan.

Draft SPS 510, which is currently undergoing public consultation, also includes specific provision to encourage trustees to consult with APRA on questions of independence. Our experience with similar provisions applying to the banking and insurance industries (as well as the responsible persons power in SPS 520 – where we can determine who is or is not a responsible person) is that early consultations between APRA and the entity usually provide the necessary guidance. We therefore expect that discussions between APRA and trustees on situations where they are seeking guidance on the application of the independence criteria are likely to be similarly effective in providing sufficient certainty and hence a formal application under section 88 may not be required.

As with similar application processes in the SIS Act and other legislation administered by APRA, we will consider each application made on a case by case basis. Given the wide variety of corporate structures in the superannuation industry and the complex nature of relationships between relevant parties, and obviously for reasons of natural justice, we will have to consider all relevant information prior to being able to form a view on whether a set of circumstances affects the independence of a director. As such, we are unlikely to be able to provide definitive public statements about the scenarios that will always be considered independent or not independent. We will, however, seek to develop some guidance to assist industry in relation to assessing independence, as I have noted.

We are also more than happy to meet further with industry on matters relating to independence and how we intend to administer the proposed legislative provisions.

APRA also expects to use the proposed power in section 90 (to determine a person as not independent) infrequently as the legislative definition of independence should provide sufficient information to undertake a robust assessment of a director’s independence in most circumstances. APRA will also provide supporting guidance to assist RSE licensees as they undertake such assessments.

And of course, APRA would not make such a determination without strong reasons, following extensive consultation between APRA and the trustee, and detailed consideration of all relevant circumstances.

Something that has seemingly been missed in the public debate is that a determination of non-independence is not a decision of the same magnitude as, say, a disqualification decision.

A decision under section 90 will only apply:

- in the context of the trustee making the appointment – it does not necessarily follow that the person would not be considered independent on another trustee board;

- at the point in time when the decision is made – independence is something that the legislation accepts can and will change over time; APRA may also put an expiry date on a determination if appropriate in the specific circumstances; and

- in respect of ‘independent seats’ on the board – there is nothing stopping a trustee choosing to appoint the person as a non-independent director if they otherwise meet the fit and proper criteria and the independence criteria on the board as a whole are met in other ways.

‘Scale test’ implementation

Let me now turn away from governance to another topic that I am often asked about: APRA’s expectations in relation to the annual “scale”, or “member outcomes”, test for MySuper products. This is an area I have touched on in other forums and we will be increasingly focusing on it with trustees as part of our regular supervision.

This assessment is something that all MySuper trustees must undertake – it is not just required for smaller funds. As an aside, I would note that this type of assessment – that is, an assessment of whether the fund is delivering appropriate outcomes for members - is actually relevant for all funds to consider, not just those with a MySuper product.

The assessment involves qualitative and quantitative aspects, to support the trustee in forming a view as to whether members in their fund are disadvantaged relative to members of other MySuper products. APRA expects all trustees to be undertaking this assessment in a rigorous and comprehensive way, with a robust framework in place looking at a range of factors based on clear criteria. We expect that some relatively small funds will be readily able to satisfy an assessment that looks at member outcomes in the context of a wide range of factors; it is equally relevant that larger funds also demonstrate that they are delivering sound outcomes for their members.

The assessment should not just focus on investment performance or fees relative to peers. It is also important to consider net returns, performance relative to the benchmarks established by the trustee, and the benefits and services provided. Further, in looking at investment performance, long term returns relative to the investment objective that has been set should be the key measure, rather than short term or peer comparisons. After all, the assessment should be about ensuring the trustee is delivering value and sound outcomes for members over the long term.

There should also be a very strong link with the strategy and business plan for the fund. In other words, the strategy and business plan should set out how the trustee expects to deliver sound outcomes for members; the assessment undertaken monitors whether the trustee is delivering effectively on its strategy and business plan. So it is just sound business practice. APRA will be looking to trustees to be able to explain why they believe their business and strategic plans are sustainable in the long run – and we will be looking more closely for evidence that the trustee is setting their strategic direction, undertaking appropriate business planning, monitoring progress against those plans, and taking necessary actions should outcomes not be as expected.

As I have said before, at times this will mean making difficult decisions, such as deciding that the strategy that is in the best interests of fund members is to transfer them to another fund. APRA expects boards to be prepared to take those hard decisions, acting in the best interests of their members rather than self-interest.

What's next?

So, what else is on APRA’s agenda?

Effective implementation of the prudential standards will be an ongoing focus of our supervision activities, with particular focus on governance, risk management and risk culture. These are inherently linked: it is very difficult to have robust governance practices if the risk culture of the organisation is poor. In APRA’s view, there is still some way to go in parts of the superannuation industry to really understand the difference between compliance and risk management. A robust compliance framework to ensure adherence with regulatory requirements is important, but just meeting minimum requirements is not enough. APRA is looking for trustees to develop a risk culture and approach that is truly focused on identifying and effectively managing risks, and which seeks to meet the spirit and intent, not just the letter, of the prudential requirements – you will see our supervisors focusing in this area in the coming year.

We are likely to identify further areas for thematic review in the coming months as we work through our internal planning processes. One area that it is likely we will be paying close attention to is how trustees identify and manage strategic risks. We support innovation and modern thinking by trustees, but we will be looking to ensure that trustees’ ambitions are matched by their operational capacity to effectively deliver on those ambitions.

Questions

So let me conclude with some final observations.

The superannuation industry has experienced significant change over many years. APRA’s experience suggests that some trustees view change as an opportunity to enhance the way they do things and so embrace it. The governance reforms are another step along the change journey for the industry.

Strong governance is essential to the future of the superannuation industry. It has many elements but first and foremost it starts with the board – its composition and the way it operates. As I said in my introductory comments, the proposed requirements in the Bill – which are aligned with APRA’s long-standing thinking on governance arrangements – together with our supporting prudential standards, provide an ideal catalyst for all boards to reflect on their governance arrangements, review the changes that are needed and take steps to refresh their approach. I would encourage all of you to seize this opportunity.

Footnotes

- Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Trustee Governance) Bill 2015 (http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId=r5548)

- Governance requirements for RSE licensees

- http://fsi.gov.au/consultation/submissions20140520/ and http://fsi.gov.au/consultation/second-round-submissions/

- Refer to http://eganassociates.com.au/infographic-director-tenure/

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.