APRA Member Geoff Summerhayes - Speech to the Members Health Directors Professional Development Program

Stable but serious

I’d like to start by acknowledging the contribution private health insurers (PHIs) have made to supporting Australians through this summer’s bushfire disaster; not only by paying claims to affected policyholders, but also by making donations or providing premium relief to victims. It is great to see PHIs supporting the Australian community in a time of need. It’s also another reminder that the physical impacts of climate change don’t just impact on the general insurance sector, and I’ll have more to say about APRA’s plans in this area shortly.

In four days’ time, it will be exactly two years since I last formally addressed a Members Health event. In my speech that day, I expressed APRA’s growing concern about the risks posed to both the industry and its policyholders by the twin challenges of declining affordability and adverse selection. I stated at the time that APRA had no prudential concerns about the state of the private health insurance industry, but noted I wasn’t sure how much longer that would be the case.

My blunt message today is that it’s no longer the case.

Over the past two years, the factors threatening the sustainability of PHIs have only become more acute. Hospital coverage has declined further. The younger, healthier cohort that financially underpins our community-rated system continues to abandon or shun private cover. Claims costs are rising faster than premium growth, cutting insurers’ profit margins. The Grattan Institute’s description of a “death spiral” may be dramatic1, but it’s also pretty accurate: on current trends, APRA predicts we’re only a few years away from seeing private health insurers forced to merge or fold, with the smaller insurers, represented in this room, likely to be the most vulnerable. That would not only be bad for those insurers, but it risks poor outcomes for their policyholders.

The situation isn’t yet critical; for now, I would describe it as “serious but stable”, however that stability is under threat. We’ve reached the point where some hard decisions need to be made if private health insurance is to remain an essential part of the Australian health system. Neither insurers, regulators nor Government can do this on their own, meaning a whole-of-industry response will be necessary to start reversing the spiral, and where all stakeholders accept that there may be no perfect solution.

Prognosis negative

Comparing the industry’s vital signs now with when I last faced you two years ago, one of the most remarkable features is how little has changed – which is not the positive endorsement it first appears.

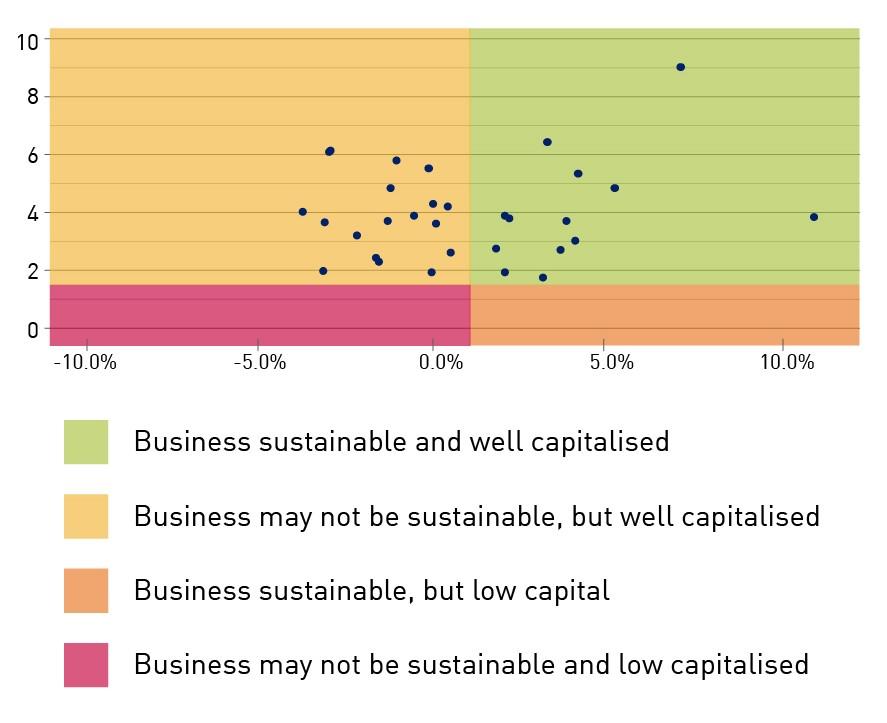

On the plus side, profitability remains strong, despite a slight decline over the past year, and PHIs continue to be well-capitalised, just as they were in 2018. That’s important, because it means policyholders can be confident their insurer has the financial means to pay all legitimate claims it receives. But the negative trends that are slowly strangling the industry’s sustainability have also not improved, in spite of APRA’s increased supervisory intensity and Government reforms aimed at addressing the affordability conundrum.

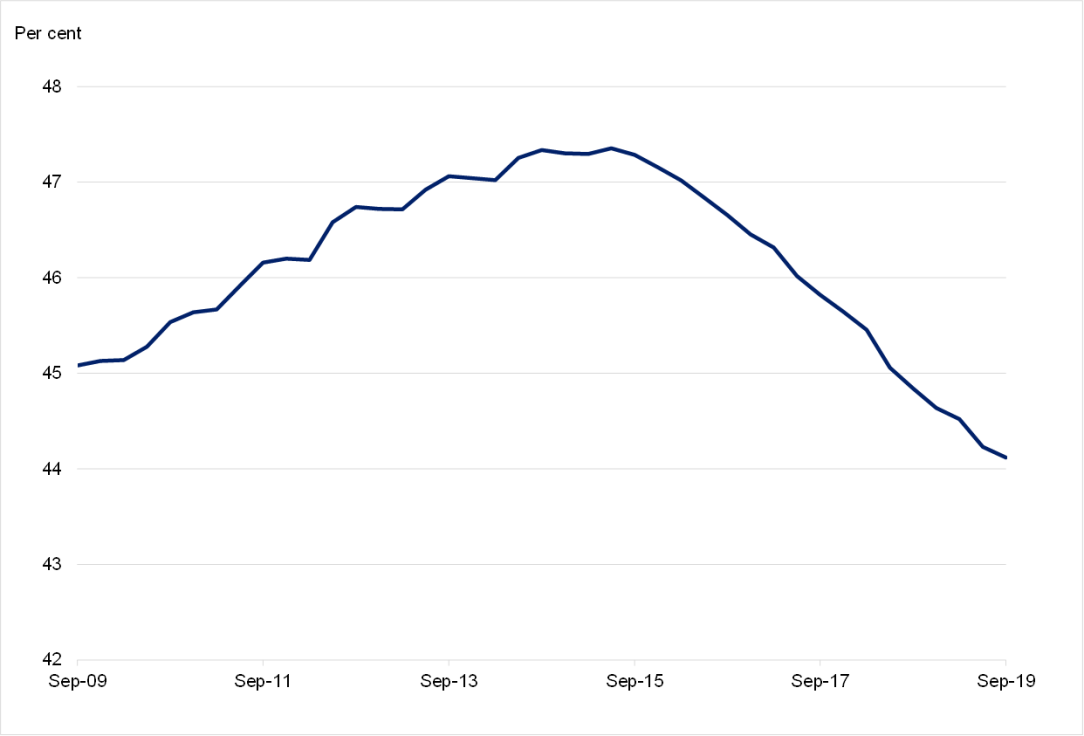

Hospital coverage has fallen from 45.5 per cent of the population in March 2018 to 44.1 per cent today. It’s now at the lowest level since June 2007.

Chart 1: Hospital treatment coverage (as a share of population)

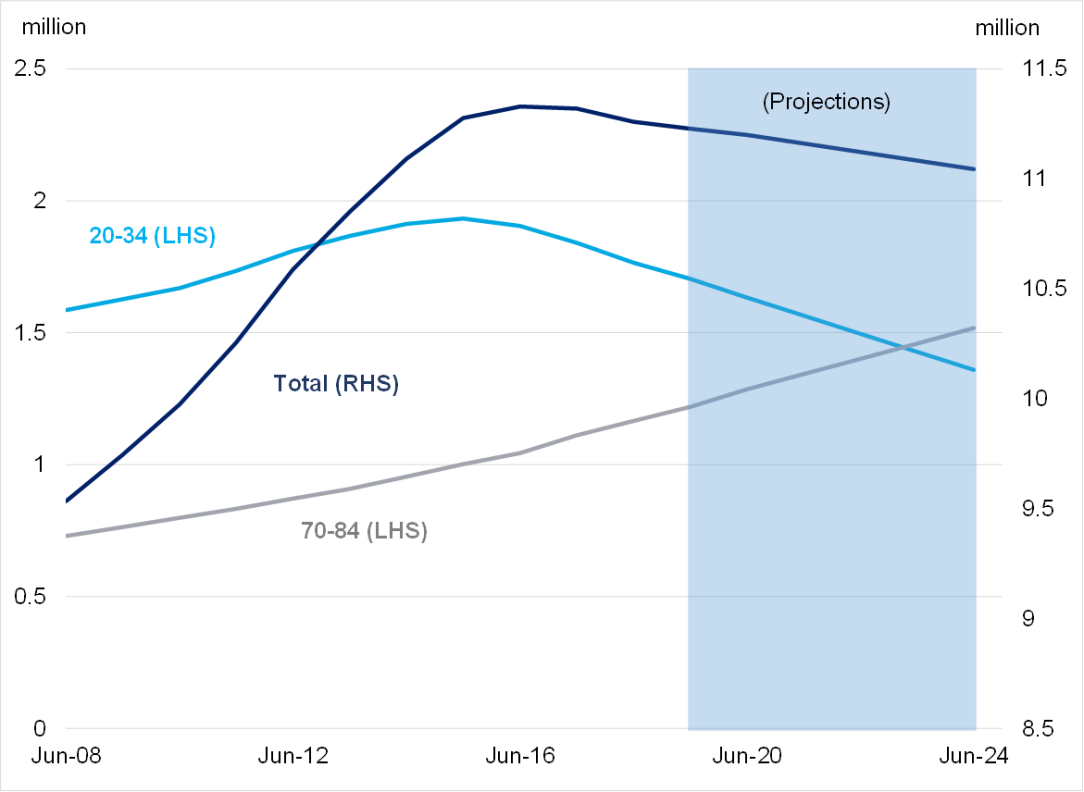

The decline continues to be driven by an exodus of younger, healthier policyholders: another 127,000 policyholders in the crucial 20-34 age group have left the private system in the past two years. The fact that’s been offset by an ongoing rise in policyholders in the 70-84 age group makes the situation worse in an economic sense, because those are the members who typically claim the most in benefits and are cross-subsidised by younger members.

That brings me to claims costs. APRA’s view has long been that the primary driver of rising premiums has been increasing costs in the system, through the price of medical treatments and equipment, and an ageing membership base that makes more expensive claims more often. Over the past few years, the underlying claims cost has risen at an average of about 5 per cent a year, putting further upward pressure on premiums.

Yet premiums are not rising at the same rate. In the past two premium rounds, premiums have risen by an average of 3.25 per cent and 2.92 per cent respectively, which is around 2 percentage points lower than the rise in the underlying costs. That money has to come from somewhere, and at the moment it’s effectively coming from policyholders as squeezed PHIs respond by increasing exclusions, increasing excesses, closing products and generally seeking to reduce claims costs. Annual premium growth might be falling, but so is policyholder value, which may explain why efforts to supress premium growth haven’t stemmed declining levels of coverage.

Something else that’s not changed from February 2018 is APRA’s prediction that the proportion of the population covered by private health insurance is likely to fall further. On current trends, we forecast the level of hospital cover will have dropped another 1.6 per cent, or 184,000 policyholders, by 2025. Not surprisingly, this decline is expected to be driven by the younger population with the loss of another 345,000 persons in the 20-34 age group, which we forecast will be partially offset by the addition of another 298,000 members in the 70-84 age category.

Chart 2: Hospital treatment membership by age

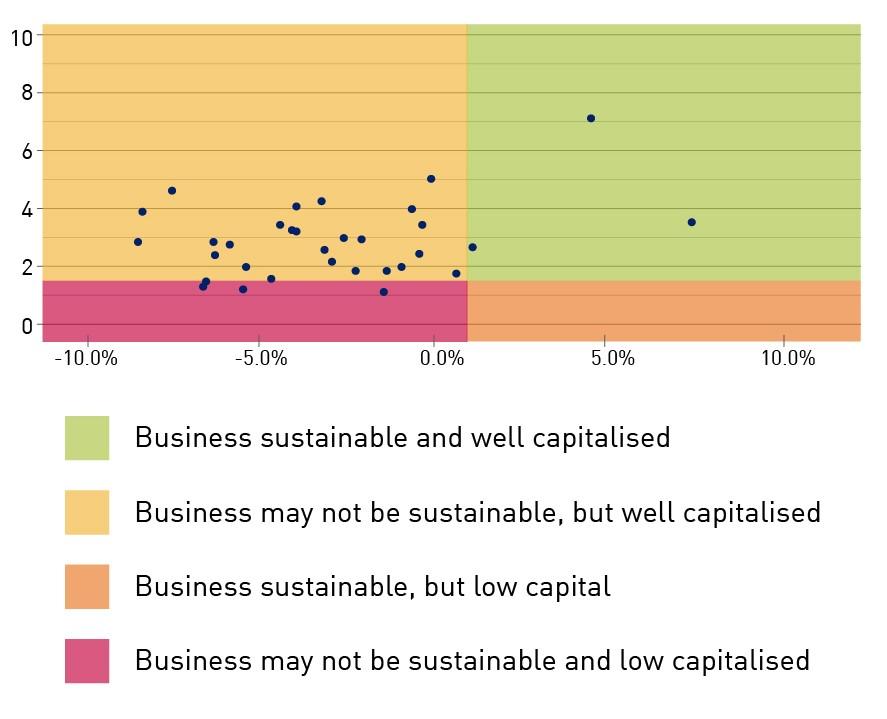

Our more immediate prudential concern, however, is the rising disparity between growth in claims costs and premiums. If the gap between the two remains at around two percentage points a year, APRA’s analysis indicates that only three private health insurers will still have a sustainable business model by 2022. None of those three are the smaller, not-for-profit funds represented by Members Health.

Chart 1: APRA’s analysis of insurer positions at December 2019 | Chart 2:APRA’s analysis of insurer positions, at March 2022 assuming benefit growth of 5% and premium increases of 3% per year |

|  |

Recovery position

With responsibility for overseeing the prudential soundness of banks, insurers and superannuation funds on behalf of deposit-holders, policyholders and members, APRA’s primary focus in addressing these concerns has been on lifting PHI resilience. We’ve placed particular emphasis on risk management, governance and capital – the three phases of our PHI Roadmap.

We’re on the record expressing our disappointment about the industry’s progress responding to the sustainability challenge, with too many PHIs seemingly waiting for the Government to find a miracle cure. In response, we asked all insurers to submit a robust, proactive recovery plan, including a “Plan B”, with “at risk” PHIs asked to sound out a potential merger partner in case their plan isn’t successful.

The first tranche of those recovery plans, from the insurers we classified as “highest risk”, were submitted in December, with the bigger PHIs’ plans due by 30 March and the remainder to submit their plans by end-of-June. APRA will assess these recovery plans, and intensify supervision according to each plan’s comprehensiveness and credibility, consistent with our risk-based approach. In this regard, we will be assisted by work we have underway to refine the metrics we use internally to better identify which PHIs face the gravest sustainability challenges. Designed in conjunction with our Cross-industry Insights and Data Division, the new tool will operate similar to the MySuper heatmap, but will only be used in internal analysis and discussions with PHIs.

We have observed positive signs from some PHIs that are tackling the sustainability challenge head-on. More successful strategies include enhancing value for younger and healthier members outside of typical hospital settings, lowering claims costs through alternative models of care and preventative health, and the use of partnerships and technologies to manage operational costs. Such progress should be recognised and encouraged.

Regrettably for this audience, it is the larger PHIs that have been most active in these areas to date. That’s not surprising, given their deeper pockets, better access to resources, technical sophistication and expertise. Larger PHIs have been able to use their health-related business to enhance customer value, some are exploring the use of artificial intelligence and robotics to increase operational efficiency, while their scale advantage supports a stronger negotiating position with hospital and medical services providers.

Smaller PHIs have their own natural advantages: specialised knowledge of niche markets, deep connections to local communities and a not-for-profit ethos that appeals to many customers. Realistically, however, smaller funds have less ability to absorb the cost pressures or invest in the types of innovative service and technological solutions that the top five PHIs are exploring.

This, however, will not be accepted by APRA as an excuse for inaction. Rather, it makes it all the more important that PHIs concentrate on those lower-cost factors they can better control, particularly in the areas of governance, business planning and risk management. Boards should be asking:

- Do we have the right expertise and capability in our organisation?

- Do we have a sustainable business model? Can we reverse the trend? If not, what are we doing about it?

- Do we have a unique product offering, or anything that gives us a competitive advantage?

- Are our risk management capabilities adequate for our operating environment?

- Are we taking proactive steps to guarantee a bright future, or simply relying on Government intervention?

In assessing the credibility of PHIs’ recovery plans, and considering our supervisory response, you can be sure APRA will be asking the same questions.

Stitching up a deal

There is, of course, a way for smaller PHIs to very quickly increase scale and financial resourcing – and that is to pursue a merger.

I have previously said that a ‘Plan B’ should be considered as part of the strategy for PHIs – and this was also part of APRA’s message to insurers last year. APRA made clear that ‘at risk’ insurers should consider potential merger partners, and start discussions early, to put them in a stronger position to act quickly if their position becomes unviable. This level of preparedness not only benefits the PHI, but more importantly, helps to protect its policyholders.

When I last spoke to you, I mentioned that APRA had yet to form a view on whether industry consolidation in private health insurance is necessary to protect policyholders’ interests. That’s broadly still true, but as smaller PHIs take limited action to address affordability challenges, we’re increasingly coming to the conclusion that it’s probably inevitable.

In response, APRA has begun preparing to ensure we have sufficiently developed processes and powers to facilitate – or force, if necessary – mergers or transfers of policies if we come to the view that policyholders’ interests are under threat. Having only taken over regulatory responsibility for private health insurance in 2015, APRA’s regulatory powers are less robust than for general or life insurance, and some weaknesses around our licensing and enforcement abilities were noted in last year’s Capability and Enforcement reviews. The Government has agreed to consider these issues. Reviewing our prudential powers for PHI has been a valuable step to inform our engagement with the Government on how to close legislative gaps that may impede our ability to act quickly to prevent or resolve a failing insurer. As I stated two years ago, APRA has no desire to see health funds that have served their communities for decades lose their unique identities through mergers, or possibly be forced to wind-up. But we will not allow sentimentality to get in the way of protecting policyholders’ interests.

Surgical intervention

By strengthening and being more active in enforcing the prudential framework for private health insurance – including the current review of capital standards – APRA is giving PHIs the best possible chance of remaining viable in a challenging environment. But “resilient” is not the same as “impervious”. Unless the root causes that are driving up premiums and costs and pushing down coverage levels are addressed, all APRA is really doing is just buying time for vulnerable PHIs, and delaying the inevitable mergers and exits to come.

In same way, PHIs can bring in fresh thinking and expertise to improve their decision-making and business planning; they can develop innovative means of delivering services, or develop product offerings aimed at attracting younger, healthier policyholders. But many of the primary drivers of the industry’s sustainability crisis largely beyond their control. PHIs can do nothing about the ageing population, which is pushing up the cost of claims. They can’t influence the persistent low wage growth that exacerbates declining affordability. They have limited control over the price of medical treatments and services. They don’t even have the same flexibility to adjust their premiums and product offerings as other insurance sectors.

As much as APRA has been critical of PHIs complacently waiting for the Government to rescue them, historically, the main driver of membership growth in Australia’s private health system has been changes in government policy: the introduction of Medicare surcharge in 1997, the 30 per cent rebate in 1999, followed by Life Time Health Cover in 2000. The one constant with all these reforms is that any relief has been temporary, because none have tackled the root causes of the sustainability problem. Even last April’s Government reforms2, with a welcome focus on making the system more efficient and easier for consumers to understand, have so far failed to arrest the decline in coverage.

A new approach is urgently needed, and it must be a whole-of-industry response. One option that APRA would support is an independent review of Australia’s private health insurance system led by appropriate qualified experts and involving all key stakeholders. APRA believes that all key policy and regulatory settings should be up for discussion: these include the ongoing viability of the community rating model, what services can be covered, the way premiums are set, and the way prices are set between PHIs and medical providers. The role of private health insurance in mental health needs to be looked at, as well as the rules around out-of-hospital treatment, and the management of chronic health conditions. Its starting point should be this fundamental question: what is the role of private health insurance in Australia?

Another area that should be looked at is the risk equalisation pool, which transfers funds from PHIs with lower than average claims costs to those with higher than average claims costs. In 2016, not long after joining APRA, I attended a meeting with a major technology company to discuss their plans to partner with PHIs, using telematics to encourage healthier lifestyle decisions among policyholders. The idea was that it would lead to fewer claims for insurers, and lower premiums for customers – a win-win. Their plans were well advanced, they’d done their due diligence and were very excited about the potential opportunities in this area. I can still remember the aghast looks on their faces when we informed them about the risk equalisation pool. It was as though we’d launched a surface-to-air missile through their business case, as they realised there was no real incentive for insurers to perform better; any efficiency gains would be shared among poorer performing insurers. There was no follow-up meeting, and, as far as I’m aware, they didn’t pursue the opportunity further.

To be clear, APRA has no formal position on the risk equalisation pool, nor any of these other matters: they are, appropriately, decisions for Government. And we also recognise there are potential downsides to altering or removing some of the current settings. For example, scrapping or recalibrating the community rating model to lower premiums for younger, healthier policyholders would inevitably push up premiums for older, sicker members. These are complex issues and there are no easy answers. What we do have a firm position on is that the industry’s current trajectory is unsustainable; and that while private health insurers may be the ultimate victims of the so-called death spiral, policyholders will be the first casualties through higher premiums and reduced benefits.

Spiralling into control

Anyone who’s watched a spiral wind chime twisting in a breeze would know they can turn in either direction depending on which way the wind is blowing. Right now, strong and persistent headwinds are blowing private health insurance ever closer to the point where the majority of PHIs are unsustainable, with potentially serious implications down the track for Australia’s hybrid healthcare model. Smaller PHIs with fewer resources to draw on are likely to be the first to succumb.

Reversing this direction will require difficult conversations and even tougher decisions involving all the industry‘s major stakeholders, including Government, insurers, regulators, medical practitioners, hospital groups, as well as device manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies and of course the views of health fund members. All have a role to play in keeping the system affordable, accessible and sustainable, and no single stakeholder can fix the issues in isolation.

When not even substantial taxpayer subsidies and the Medicare levy surcharge can convince a growing number of policyholders that private health insurance represents value-for-money, it’s time for a rethink. For now, PHIs are profitable, well capitalised and comfortably able to meet their obligations to policyholders, but that will not remain the case much longer without major structural and policy reforms. We should not wait for the industry’s stable but serious condition to become critical before operating to save it.

Footnotes:

1https://grattan.edu.au/confronting-the-private-health-insurance-death-spiral/

2https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/private-health-insurance/private-health-insurance-reforms

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.