APRA Chair Wayne Byres - Speech to the Financial Review Banking Summit 2022

A fit-for-the-future banking sector

Good morning everyone, and thank you for the invitation to participate in this year’s Banking Summit.

Notwithstanding Donald Horne’s intent when he penned the phrase, we are in many respects truly a lucky country. Despite the travails of the past couple of years, Australia remains a prosperous country blessed with many opportunities before it to grow and improve our nation’s living standards. The theme for this year’s event – ‘Funding the recovery’ – is therefore an important one because the financial system plays a critical role in allowing households and businesses to grasp those opportunities.

There are, of course, challenges ahead: the legacy of the pandemic, the resurgence of global inflation, and ongoing geopolitical tensions, to name just a few. The next few years will be far from plain sailing. But we start with a strong financial system, well-equipped to handle bouts of bad weather and changing conditions.

Given today’s agenda is focused on how the banking sector will help Australia grasp the opportunities before it – helping us remain a lucky country, if you will – I plan to spend my time talking about some of the ways APRA contributes to that goal.

The financial foundations

This is a banking summit, but I want to start with a broader perspective.

If Australia is to successfully fund the opportunities before it, the financial system needs to provide three things: debt; equity; and insurance. All three need to be both available and affordable to support economic growth and the ongoing prosperity of the Australian community. Are the foundations in place?

In Australia, the provision of debt occurs primarily through the banking system. That is hardly unusual, although the absence of deep debt capital markets means the share of debt financing provided through bank lending is high relative to some other advanced countries.

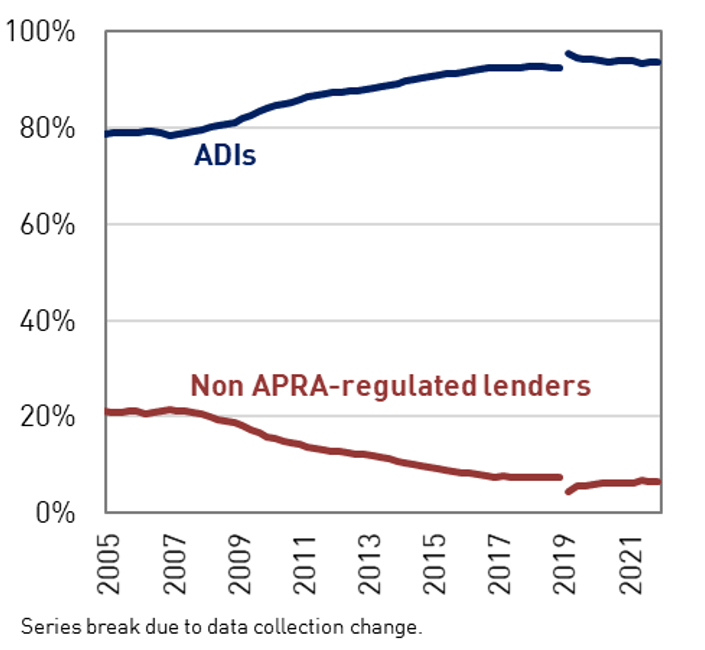

The very largest corporates can access international capital markets but for many Australian companies, debt is obtained by sourcing loans from Australian financial institutions. If anything, the banking system has become more dominant in the provision of lending in recent years. Measures of aggregate lending indicate the share of lending provided by the banking sector, which had hovered around 80 per cent prior to the GFC, rose to well over 90 per cent in the aftermath, and has remained there since. Broader measures of non-bank financial intermediation as a share of the financial system have shown a similar trend. And those trends have occurred during a time in which regulation has been strengthened – prima facie, it has not harmed (and may even have helped) the relative competitive position of the regulated sector vis-à-vis the unregulated sector.

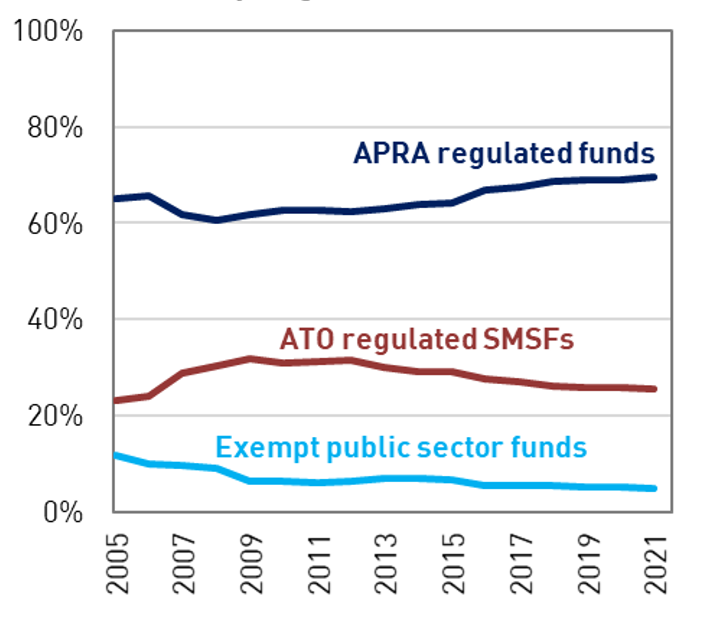

(As an aside, a similar story emerges in superannuation. Starting with the Stronger Super reforms in 2013, the APRA-regulated superannuation industry has undoubtedly experienced a strengthening of regulation. It does not appear to have slowed the growth in the share of superannuation assets held by APRA-regulated funds.)

Share of total lending by regulated status | Share of superannuation assets by regulated status |

|  |

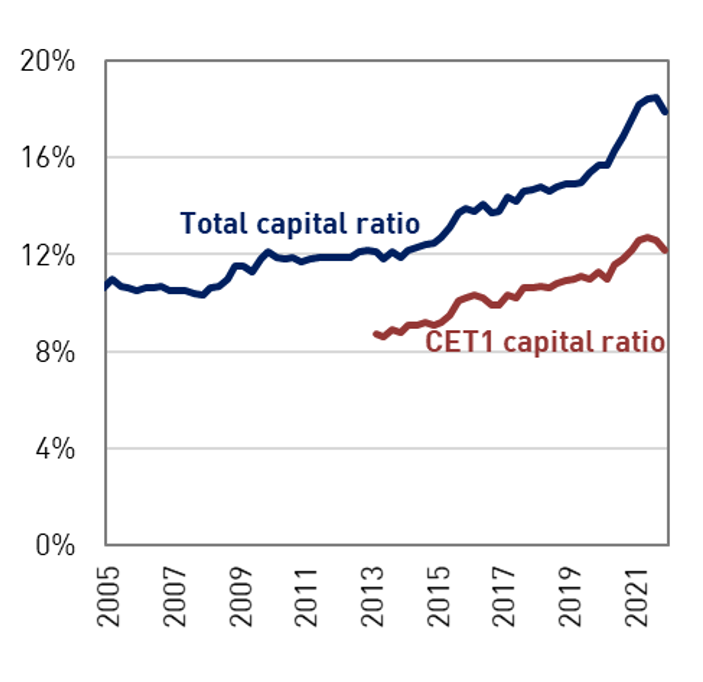

That prominence makes the financial health of the banking industry critical. A key lesson of recent crises has been that a strong banking system can borrow and lend; a weak banking system struggles to do either. The good news is that after a decade of reform and resilience building, Australia is fortunate to have a strong banking system. It is well capitalised, in both historic and international terms. It also has a stronger funding profile than years gone by, and remains highly rated with good access to international markets.

ADI industry capital ratios

When it comes to equity finance, the superannuation system is a key provider to Australian industry. That was never more evident than in the depths of the COVID crisis when many Australian companies – including banks – sought to bolster their balance sheets. Despite also grappling with an expansion of the Early Release Scheme, which allowed fund members to withdraw their savings to assist with the financial strains from COVID, Australian superannuation funds were key investors in the capital raisings of that time.

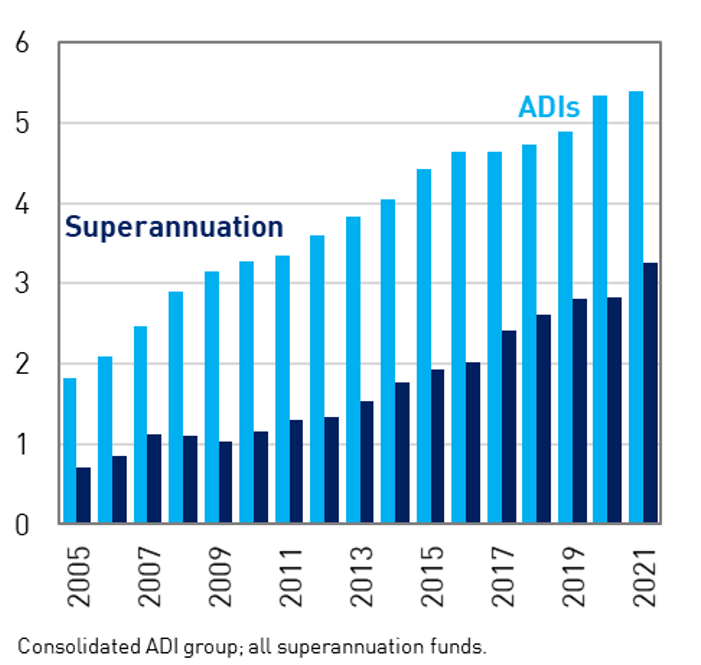

Over the past decade and a half, Australia’s pool of superannuation savings has grown strongly, both in absolute and relative terms.1 That provides a very healthy flow of new savings that need to continually be invested for the long-term. Obviously, not all of that will be invested domestically or in equity, but having such a large and growing pool of savings that needs to be invested for the long-term can only be beneficial for funding the Australian economy.

Total assets

($ trillions)

What about insurance? Here, the picture is slightly less positive. As with banking, Australia’s insurance industry is financially sound, and has navigated the past few years well. But as I noted recently,2 the industry and the community it serves are increasingly challenged by issues of insurance affordability and availability. A range of factors – poor product design, rising claim costs, increasing litigation, and a changing climate – mean that insurance is increasingly more expensive and, in some sections of the market, harder to find.

Given insurance is often critical to making projects investable for debt and equity providers, this problem is something that warrants serious attention by policymakers and industry participants alike.

This is a banking conference, so I will not dwell on this issue much further. But it is important that we recognise the issues of insurance affordability and availability have an impact on many aspects of economic activity, and the issue is growing in urgency. Putting our collective thinking caps on to solve some of the current challenges is in everyone’s interests.

The impact of regulation on the financial landscape

Turning more specifically to banking, a financially sound and resilient banking sector will be essential to funding the recovery. So will a competitive one.

As you all know well, our goals when it comes to banking are to protect bank depositors and promote financial stability.

That said, we do not pursue a ‘safety-at-all-costs’ strategy. The APRA Act requires that in pursuing our primary safety objective we also have regard to considerations of efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality. The Act also says that in whatever trade-offs we make, our decisions and actions should always be directed towards promoting financial stability. You might therefore call it a ‘stability-at-least-cost’ mandate.

It is sometimes said stability and competition are fundamentally at odds with one another. That has never been our view. Competition brings innovation and enhanced outcomes for customers, and good regulatory settings in the financial sector should deliver financially strong competitors, creating both financial stability and a dynamic marketplace for financial services. As we saw during the COVID period, the community will be best served by strong competitors who are sufficiently resilient to support their customers both in good times and bad.

That is not to say the issues of competition and stability do not sometimes involve a trade-off. Moreover, not all competition is unambiguously positive. Our interventions in relation to housing lending over the latter part of the last decade had the explicit goal of dampening competitive spirits. Those spirits were playing out in a manner – through poor lending standards – that was likely to be damaging to the community in the long run.

So, broadly speaking, we are not tasked to promote competition, but we certainly try to support it unless it is materially threatening our stability mandate.3

Given there has been a lot of new regulation over the past decade, it’s useful to look back and see whether it is possible to discern any major impact on the shape of the banking industry.

One hypothesis might be that increased regulation has favoured non-banks over their bank competitors. A second might be that, given regulation often involves fixed costs, regulation has the unintended effect of strengthening the competitive position of the largest banks who are best placed to bear it. A third hypothesis might be that, particularly with a strengthening of capital requirements, mutual ADIs in particular would find it harder to compete.

None of these hypotheses are immediately apparent in the data:

- I’ve already noted that the banking industry seems to have become more dominant in the provision of lending over the past decade. Being financially robust, well-rated and regulated appears to have its advantages.

- The longer-term growth in the share of banking assets held by non-major banks – which was severely set back by GFC-related acquisitions and the associated flight to quality – has recommenced in recent years as smaller players again attract a larger share of new business.4

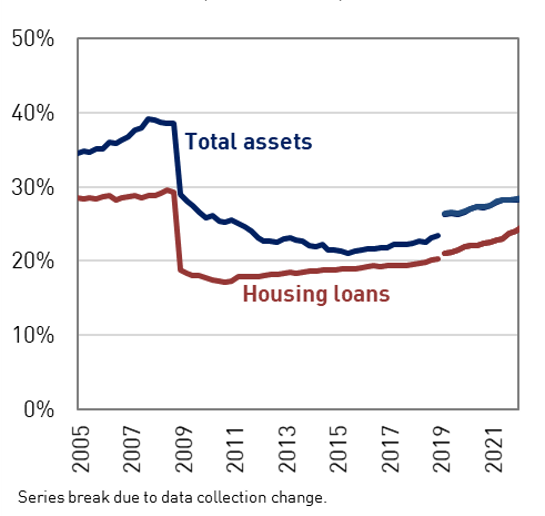

Share of non-major ADIs

(Domestic books)

- While the number of ADIs in Australia has continued its steady decline, clearly driven by a reduction in the number of mutuals, the share of industry assets (and mortgage lending, their primary product) held by the mutual sector has been remarkably steady and, if anything, been inching fractionally higher in recent years. In other words, the trends in the mutual sector are reflective of that for the non-major bank sector more broadly.

Number of ADIs

In making these observations, I readily acknowledge that it is difficult to know what the counterfactual might be, and that what I have said is very much at the aggregate level. And I also acknowledge that while each of these observations does not immediately point to an excessive regulatory impost – nor, I should quickly add, imply there are no benefits from reducing regulatory burden – there will no doubt be arguments that the gradual shifts in the competitive landscape are not significant enough for everyone’s liking, and that more could be done to promote competition.

As I have said, APRA does not have a competition mandate, but in recent years we have been particularly conscious of examining where and how the regulatory burden falls, and doing what we can to limit the application of new regulation to where it is needed. To give some examples of how we’ve approached that task in recent years, I would point to:

- graduated approaches to regulation which avoid undue costs on smaller competitors;5

- facilitative measures that promote more active competition;6 and

- simplification efforts that reduce compliance costs.7

Individually, none of these measures will materially alter the competitive landscape. But collectively, they show how APRA has been working to make sure our regulatory requirements are applied proportionately, and we actively support competitive outcomes where they are not at odds with our safety and stability objectives.

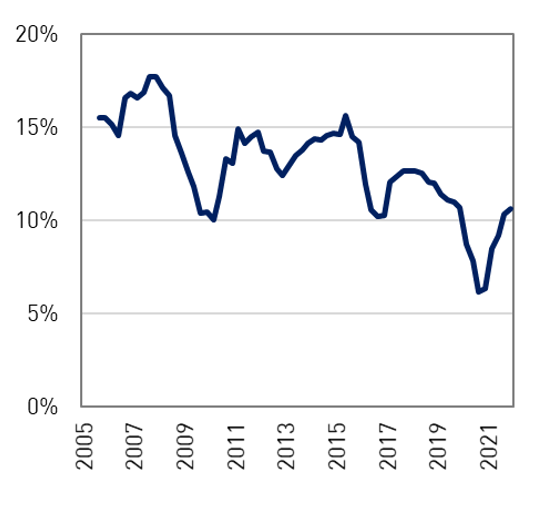

Before I move on to other topics, I want to acknowledge one area where increased regulation, particularly capital requirements, has had a clear impact – on returns to shareholders. In setting higher capital requirements, our a priori assumption was that, in a competitive marketplace, banks would not be able to sustain their returns by passing the full impact of regulation onto their customers. That has certainly been borne out, especially over the period since 2015 as the Basel III and ‘unquestionably strong’ reforms were built into the system. The industry’s RoE has therefore declined notably.

ADI's return on equity

(Consolidated group)

Looking ahead

Let me now turn to some of our regulatory and supervisory priorities. There are three issues I want to touch on – housing, climate, and innovation – all of which are on today’s agenda.

I will start with housing.

Housing loans currently make up just over 60 per cent of the banking industry’s total loan portfolio. That share has gradually grown over time.

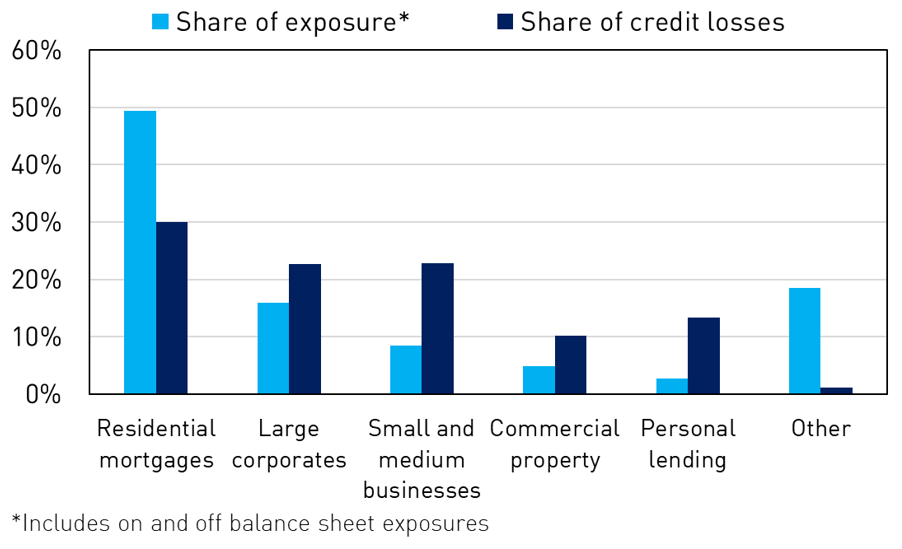

Historically, housing loan portfolios have been low risk, and acted as ballast for the industry through turbulent periods. Large credit losses have traditionally come from elsewhere – most notably, from corporate lending and commercial property. Housing loans have been, as they say, as safe as houses.

That may not be the pattern in the future. Aggregate dollar losses from housing portfolios now regularly exceed that from other portfolios in our stress tests. Of course, that can simply be a product of the calibration of the stress test itself, but more intuitively it reflects the combination of a growing proportion of housing loans in the total book, and rising risks within those portfolios from a larger share of more heavily indebted borrowers.

Stress test credit losses by asset class

That is why APRA has been increasingly exercised (and, at times, interventionist) in recent years about the quality of housing lending, and why our proposed new macroprudential framework has a significant focus on measures to constrain housing-related risks.

We are now entering a very different environment than has existed for much of the past decade. The faster-than-expected emergence of higher inflation and interest rates will have a significant impact on many mortgage borrowers, with pockets of stress likely, particularly if interest rates rise quickly and, as expected, housing prices fall.

Of particular note will be residential mortgage borrowers who took advantage of very low fixed rates over the past couple of years, and may face a sizeable ‘repayment ‘shock’ (possibly compounded by negative equity) when they need to refinance in the next year or two.

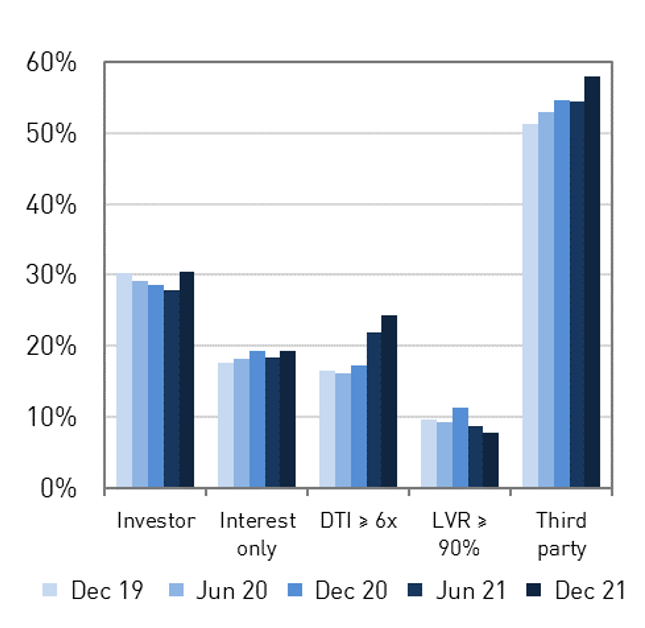

We will also be watching closely the experience of borrowers who have borrowed at high multiples of their income – a cohort that has grown notably over the past year. Interestingly, this growth has not been an industry-wide development, but rather has been concentrated in just a few banks. We therefore opted to tackle our concerns on a bank-by-bank basis, rather than opt for any form of macroprudential response. We expect lending policy changes at those banks, coupled with rising interest rates, will see the level of high DTI borrowing begin to moderate in the period ahead.

Share of qtrly new housing loans

Overall, we see the banking industry well placed to weather a more difficult environment, and we do not expect a deterioration in housing loan portfolios to cause system stability issues. And we see the expected decline in housing prices as, on balance, a positive development from a system stability perspective, reducing the need for borrowers to borrow very high multiples of their incomes. Nonetheless, given the importance of mortgage lending to the stability of Australian banking system, you can expect us to maintain a very close eye on developments.

Let me now turn to climate.

If Australia is to invest in the transition to a low carbon economy consistent with our 2050 net zero emissions target, the banking system will play an important role financing that investment. And to state the obvious, financing that investment successfully requires a good understanding of climate-related risks.

Last year, we released a prudential practice guide on the financial risks of climate change. That guide noted there are risks – and opportunities – for financial institutions from a changing climate, and the guidance was designed to help all types of firms make well-informed decisions about how to manage the risks and, hopefully, take advantage of the opportunities.

To understand whether and how the guidance was being applied in practice, we recently completed a survey of 64 medium-to-large APRA-regulated firms, including 21 of the largest banks. It has provided some valuable insights, and we will be giving thought to expanding the survey to a broader cohort in due course.

Responses from the survey were broadly positive. They showed that almost all boards had accepted their responsibility for actively overseeing climate-related risk. Most banks had also started to embed climate risk into existing elements of their risk management framework, such as their risk appetite statement, risk management strategy and business plan. When it comes to disclosure, more than two-thirds of surveyed banks are already publicly disclosing their approach to measuring and managing climate risks, with almost all aligning their disclosures to the established framework developed by the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

However, one important finding was that only around half the banks surveyed are currently assessing emissions from their lending exposures. While emissions data quality and availability make it difficult to be able to reliably measure these metrics, their absence creates two challenges. First, it makes it difficult for banks to properly understand how borrowers will (or will not) be impacted by the transition to a lower carbon world. And second, it makes it difficult for banks to satisfy the increasing demands from investors, standard-setters and peer regulators for greater climate risk disclosure. As an example, both the International Sustainability Standards Board and the US Securities and Exchange Commission have released draft disclosure standards in recent months that talk to the role of Scope 3 emissions as part of a more comprehensive disclosure framework. And we know from talking with the international investor community that they are both demanding greater transparency about climate-related risks and opportunities, and being more sophisticated in response to what they see as poor climate risk management, with a strong preference for more active engagement and shareholder advocacy, rather than simply opting for divestment.

We are also reaching the final stages of our first Climate Vulnerability Assessment (CVA), a Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) initiative led by APRA. Since early 2021, APRA has been working closely with the five major banks to assess the potential financial risks posed by both physical and transition climate risks, and to understand how the banks may adjust their business models and implement management actions in response to different future climate scenarios.

The CVA exercise has been valuable in drawing out the unique challenges banks face in understanding climate risks. These include accounting for the broad impacts of climate change across the economy, the uncertain and extended time horizon over which climate risks may materialise, and the data challenges that I just mentioned. We recognise these challenges, and I thank the participating banks for their continued commitment to this important work. We have just received the individual bank results from the CVA: we anticipate providing an update on the outcomes in Q3 this year, with final results expected to be published towards the end of the year so that others can benefit from the outcomes of the work.

The last topic I wanted to mention was innovation and digitisation, including the rapid growth in crypto-assets and the use of distributed ledger technology.

While the opportunities are significant, so are the risks – as the holders of TerraUSD found out most painfully a couple of weeks ago.

There is no doubt the Australian regulatory framework will need to adjust to new forms of money, payments and finance. Governments and regulators around the world are responding to this at varying speeds. Two particular issues are high on APRA’s agenda:

- stored value facilities and payment stablecoins, which can have the look, feel and functionality of a traditional bank deposit, but without any of the regulatory protection; and

- new business models, such as aggregator apps and banking-as-a-service, which test regulatory boundaries and can make it difficult for consumers to understand exactly who they are entrusting their money to.

APRA obviously expects banks exploring the potential to offer new and innovative forms of finance to do so based on a well-considered risk assessment. As we have done with climate-related risks, we have been careful in setting out our expectations to not preclude or prevent any particular activities. Instead, our focus has been to encourage well-informed decision-making, allowing innovation to occur without creating undue risk.

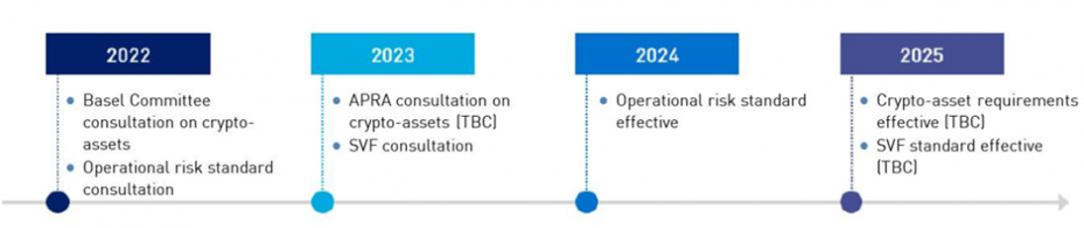

In the period ahead, our workplan in this area involves:

- consulting on requirements for the prudential treatment of crypto-asset exposures by ADIs, following further conclusion by the Basel Committee on its current proposals. I would hope we will see the next version of the latter in a couple of months’ time;

- consulting on new and revised requirements for operational risk management, covering control effectiveness, business continuity and service provider management. While these requirements will apply to the entirety of a bank’s operations, many will be directly relevant to the management of operational risks associated with crypto-asset activities. The draft prudential standard will be released for consultation in the next few months; and

- developing and consulting on approaches to the prudential regulation of payment stablecoins. The agencies of the CFR have been developing options for incorporating payment stablecoins into the proposed regulatory framework for stored value facilities. Subject to the development of the broader legislative and regulatory framework – which will depend on the priorities of the new government – we would hope to consult on prudential requirements for large SVFs in 2023.

Concluding remarks

To return to where I started, Australia is a prosperous country, lucky to be blessed with many opportunities to grow and improve our nation’s living standards. The financial system is a critical conduit through which that can happen. Funding the recovery can be thought of as a banking industry task, but other parts of the financial system need to play their part as well.

There are hazards ahead, but the banking system appears well-equipped to navigate them. Whether it is the health of housing portfolios in a rising interest rate environment, the impact of climate change, or the implications of digital innovation – all of which are big issues on your agenda today – there are undoubtedly challenges that must be overcome. But a financially strong, competitive and innovative banking system should give us plenty of confidence that we can do so.

Footnotes

1Superannuation savings grew at a compound annual growth rate of around 9 per cent, compared to 6.5 per cent for the banking system. As a result, whereas back in 2005 the superannuation system was roughly one-third the size of the banking system, it is now heading towards two-thirds the size.

2Remarks to FINSIA ‘The Regulators’ event.

3 As the Productivity Commission concluded in its 2018 report into Competition in the Australian Financial System: “Competition and stability in the financial system can — and should — coexist. But … [a]lthough the legislation that requires APRA to give weight to competition is valuable, its remit quite reasonably must favour system stability.” Similarly, the 2019 APRA Capability Review noted: “APRA’s role is not to actively promote competition. … APRA’s philosophical approach [to not unduly hinder competition] and its application is reasonable.”

4 The sharp decline in non-major banks’ market share in the immediate aftermath of the GFC is another example of the cost of financial crises – this time in terms of the cost to competition from a period of financial instability that produces significant consolidation.

5 Examples include setting differential targets for ‘unquestionably strong’ capital, with IRB banks facing larger increases; imposing additional loss absorbing capital requirements only on the largest ADIs, rather than all ADIs as recommended by the Financial System Inquiry; and tailoring our new remuneration requirements to impose more stringent requirements only on significant financial institutions, with much more modest requirements for smaller ADIs.

6 Examples include making our licensing regime easier to navigate for new entrants; and providing for the issuance of new CET1 capital instruments for mutuals to fund their growth.

7 Examples include establishing a new simplified capital adequacy framework for ADIs with assets under $20 billion (a threshold sufficient to capture the current population of mutuals); managing implementation of new requirements, such as the BEAR regime, to provide smaller ADIs a longer implementation time, and more guidance; and making changes to reporting requirements that provide for longer reporting timeframes for smaller ADIs – in some cases almost doubling the time period that small ADIs have to submit their data to APRA.

Media enquiries

Contact APRA Media Unit, on +61 2 9210 3636

All other enquiries

For more information contact APRA on 1300 558 849.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.