Achieving a stable and competitive financial system

Wayne Byres, Chairman - AFR Banking & Wealth Summit, Sydney

Good morning. I’m pleased to be able to take part in this very topical conference. Yesterday’s proceedings were undoubtedly interesting and informative, so I’ll do my best to help get today off to a similar start.

Balancing Stability and Competition

I plan to talk this morning about the objectives of stability and competition within the financial system. There are a number of desirable features of a financial system beyond those two, but they are the ones that have had most attention in the post-crisis period, and are often seen as jostling for primacy in the current policy debate.

Importantly, though, neither stability nor competition is an end in itself: we want stability and competition because they both bring important benefits to the Australian community.

It is usually taken for granted that the financial system will provide the stable, smooth and efficient transfer of funds between savers and investors that is necessary to promote economic growth and improve our standards of living. Indeed, the benefits of financial stability are often expressed in terms of the costs of not having it: for example, the higher cost of financing investment, and the disruption to activity in the real economy, that arise from uncertainty and volatility. The financial crisis showed these costs can be deeply damaging, and persist much longer than the crisis that produced them. As a result, policymakers have rebuilt large parts of the regulatory framework in an effort to deliver a more stable financial system.

We also want a competitive financial system. Competition delivers lower prices for, and greater choice and variety in, financial products; it encourages innovation; and it promotes efficiency in all its forms (operational, allocative and dynamic). Economics tells us that in the absence of market imperfections – obviously an important caveat – a genuinely competitive marketplace will deliver the best outcomes for consumers.

Of course, it’s possible to have too much of both. To borrow a phrase, we don’t want ‘the stability of a graveyard’. But we have all seen instances of excessive, or reckless, competition too. Eliminating the excess, and finding the optimum level of both, is a matter of careful balance. And, if we get the balance right, they will be mutually reinforcing: competition will support stability, and stability will support a competitive environment.

APRA’s statutory objectives

The need for balance is evident in the statutory objectives that the Australian Parliament gave to APRA.

Prudential regulators like APRA exist, in part, due to the information asymmetry between financial institutions and their customers. Consumers find it hard to judge the safety of institutions that they rely upon for their financial well-being, and a regulator is therefore needed to ensure consumers can have a high degree of confidence that the promises made to them will be met. As the Financial System Inquiry noted ‘confidence and trust … are essential ingredients to building an efficient, resilient and fair financial system.’ [1]

The APRA Act therefore tasks us to administer laws that provide for prudential regulation of financial institutions. Those laws are the industry-based Acts - the Banking Act 1959, the Insurance Act 1973, the Life Insurance Act 1995 and the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 – which charge APRA to protect the safety of depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.

It was rightly recognised, however, that it’s possible to have too much of a good thing. The Act therefore also makes clear that APRA is not to pursue a safety-at-all-costs strategy. In performing and exercising its functions and powers, APRA is to balance the objective of financial safety with considerations of efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality.

To complete the task given to us, the Act also says that, in balancing these objectives, APRA is to promote financial system stability in Australia. [2]

So broadly, our task is to:

- look after the safety of depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members;

- do so in a manner that balances safety with, amongst other things, competition; and

- strike that balance in a way that promotes financial stability.

Easy … I wish. Inevitably, this balancing act requires a considerable amount of judgement, and hence it will always be open to debate whether we have struck the right balance. For our part, we are continually seeking to improve the way in which we consider and balance these considerations, and over the year ahead will be putting more material into the public domain on how we go about this.

The benefits to competition of an integrated regulator

Before going further, I’d like to briefly comment on an issue that sometimes gets forgotten: the benefits to competition of having an integrated regulator like APRA.

One of APRA’s founding catchcries was to seek to ‘treat like risks in a like manner.’ That is, as the traditional boundaries between banking, insurance and wealth management were being blurred, the creation of an integrated regulator like APRA was seen as critical to ensuring that regulation did not distort the competitive landscape due to different requirements being placed on different licence holders doing essentially the same activity. There are plenty of ways in which this has played out, including that:

- our supervisory methodology and processes are common across industry sectors, ensuring a common approach to supervisory evaluations, and a consistent approach to intervention;

- we now have prudential standards for banking and insurance that are identical with respect to governance, fitness & propriety, risk management, outsourcing and business continuity. Although standards for superannuation in these areas remain separate, the differences are far less material than they have been in the past;

- we have developed a new framework for supervising financial conglomerates on a consistent basis, which we will be implementing in the near future; and

- for industries with capital adequacy standards, we have aligned the types of capital that can be used to meet regulatory requirements.

Of course, differences remain: it is not possible, nor desirable, to have a totally uniform framework across the diversity of institutions we regulate. But where it makes sense to do so, harmonising requirements across industry sectors has the advantage not just of consistent risk assessment, but also of fostering competition by eliminating any advantage one sector might enjoy over another due to uneven regulation or supervisory treatment.

The Financial System Inquiry

There has been a lot of debate, domestically and internationally, about whether the ‘regulatory pendulum’ has swung too far in favour of stability in the post-crisis environment. The Financial System Inquiry (FSI) was therefore a timely opportunity to consider this issue in an Australian context, particularly as Australia felt the impact, but was ultimately some considerable distance from the epicentre, of the global financial crisis.

The FSI made clear that competition is critical to the development of a dynamic and innovative financial system. But the FSI also acknowledged that competition needs to operate within a sound policy framework. To quote the Final Report: ‘Competitive markets need to operate within a strong and effective legal and policy framework provided by Government.’ [3]

In the context of the debate on the positioning of the regulatory pendulum, however, the most interesting outcome from their analysis is that, at its core, the Inquiry is advocating a set of policy changes designed to produce a more competitive and a more stable (or in the words of the FSI, resilient) financial system. It is not advocating a trade-off – that is, it is not arguing that one objective must be sacrificed to achieve the other. I think this conclusion is absolutely correct.

Indeed, the Inquiry’s conclusion is in line with that of the UK’s Independent Commission on Banking (the Vickers Report). It noted that in the pre-crisis environment there ‘was a failure in regulation, as a result of which competition was ill-directed towards excessive risk.’ [4]

The Vickers Report drew a useful analogy with pollution control. ‘If pollution control is too lax, polluters will gain business from cleaner firms as they are able to produce at a lower cost, unless the cleaner firms also reduce their costs by lowering their standards and polluting more (a ‘race to the bottom’). The solution is not less competition but proper pollution control.’ [5]

There is a clear parallel in finance, as risks to the community from instability in the financial system are not fully borne by those that generate them. In the absence of effective regulation, financial firms acting in their own interests, and in a competitive marketplace, have the potential to create financial instability and thereby impose costs on the wider community. That is very clear from the after-effects of the financial crisis.

Both the FSI and the Vickers Report therefore seek to establish a regulatory framework in which improvements to the resilience of the financial system should help, and not hinder, effective and sustainable competition and add to the welfare of the broader community. To borrow from another organisation that has studied this issue extensively, the OECD, the financial industry must be ‘competitive enough to provide a range of services at a reasonable price for consumers, but not prone to periods of excess competition, where risk is under priced (for example, to gain market share) and competitors fail as a result with systemic consequences.’ [6]

Some observations on the Australian financial system

With my comments so far as background, let me make some observations on the current shape of the Australian financial system.

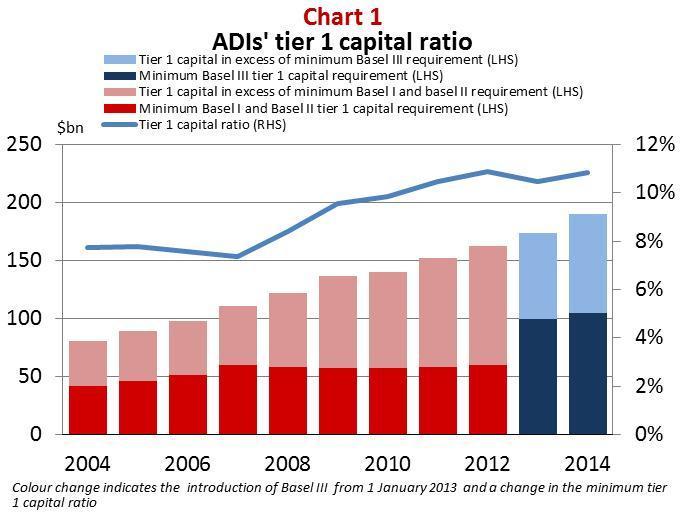

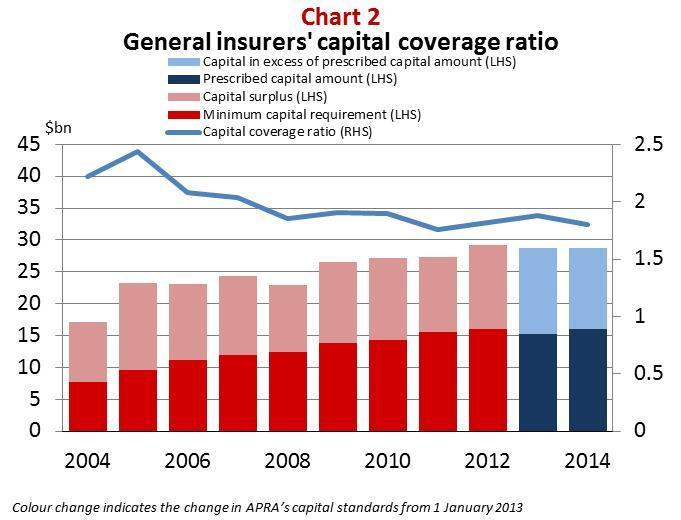

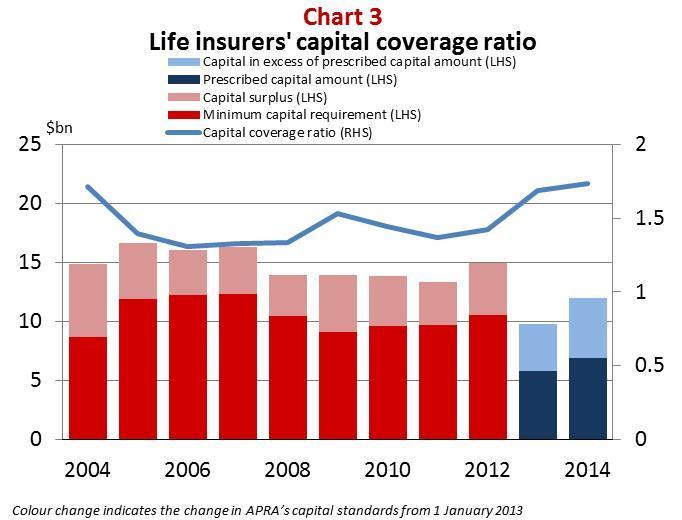

Key to having a stable financial system will be the strength of the financial institutions within it. When it comes to capital adequacy, both banks and insurers are currently operating comfortably above minimum requirements, even with the stronger regulatory capital frameworks introduced by Basel III and the LAGIC reforms now in place (Charts 1-3).

As I have noted elsewhere, for all the focus on the regulatory capital requirements, the amount of capital held by the banking industry has risen in a very steady fashion, largely in line with balance sheet growth. [7] The life and general insurance sectors have also adjusted well to their new standards; again, sensible transition has permitted the industry to adjust in an orderly manner. Although there are invariably differences at the level of the individual company, all three industries have a reasonable capacity to absorb shocks within existing capital resources, and to raise more capital when needed.

Further reforms to bank capital requirements are in the pipeline, emanating both from the FSI and the Basel Committee. While we want to deal with the various proposals in an orderly manner, I’ve made the point elsewhere that we do not need to wait for every i to be dotted and t to be crossed in the international work before we turn our minds to an appropriate response to the FSI’s recommendations. [8] Some – such as Recommendations 2 (mortgage risk weights) and 4 (international capital comparisons) – seem able to be dealt with sooner rather than later. We’ll have more to say on these issues shortly, but with continued sensible capital planning the industry is well-placed to accommodate them.

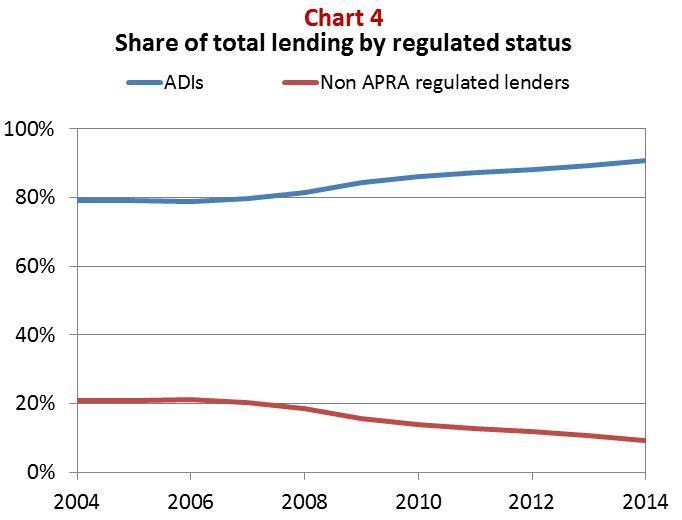

With that starting point, let’s now look at some other developments in the financial system. I’ve two charts here that examine the position of the regulated sector relative to the unregulated sector. This is obviously an important indicator of the extent to which tougher regulation might be impeding regulated institutions in their ability to compete against non-regulated institutions providing similar products or services.

The first chart (Chart 4) shows the proportion of total credit provided by regulated and unregulated institutions. This indicates a steady increase in the proportion of credit provided by regulated institutions. Whether that is a good thing I will leave for others to judge, but it certainly does not lead one to conclude that the stronger regulation introduced in the post-crisis period has adversely impacted the ability of regulated institutions to provide credit vis-à-vis that of their unregulated counterparts. Indeed, if anything, it supports the argument that we have often made: that strong financial institutions make strong competitors, and in the post-crisis world the virtues of financial strength and regulated status are likely to be of greater value than was the case previously.

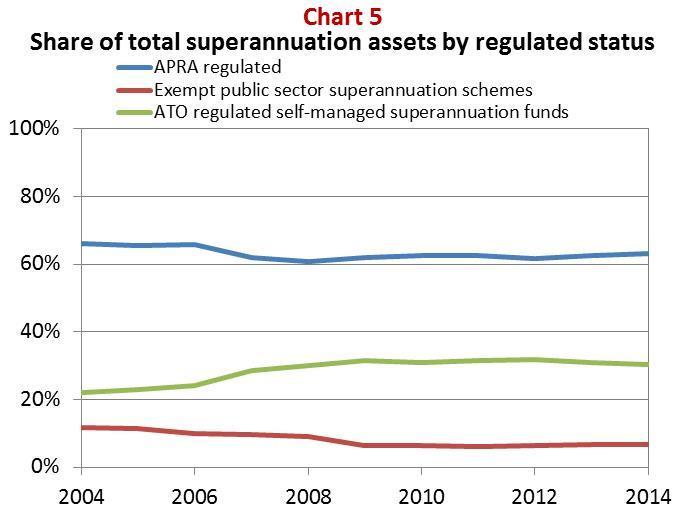

The second chart (Chart 5) looks at superannuation in light of the rapid growth of the self-managed sector. The share of industry assets accounted for by self-managed funds has certainly risen: over the past decade, by close enough to 10 percentage points. But some of this increased share has reflected the decline in relative importance of the exempt public offer schemes. After falling a few percentage points in the 2006-2008 period, the share of industry assets held by APRA-regulated funds has remained largely stable. The self-managed sector certainly provides a strong competitive discipline on the APRA-regulated sector, but there is little in this chart to suggest that the substantially more robust prudential regime introduced in recent years is materially impeding the ability of regulated funds to offer attractive products and services to fund members.

As well as having adequate capital and being competitive, APRA has a strong interest in making sure the institutions we regulate are profitable. We want regulated entities to be able to earn a reasonable return on capital for the benefit of their shareholders, so capital will continue to be invested in them as and when needed. Put simply, on-going access to new capital is important for financial stability, and establishing a regulatory regime that made it unattractive to invest capital would not be in the community’s long term interests.

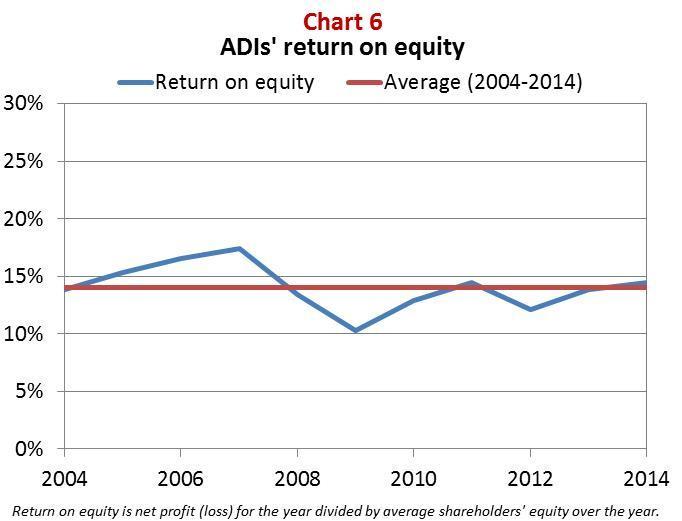

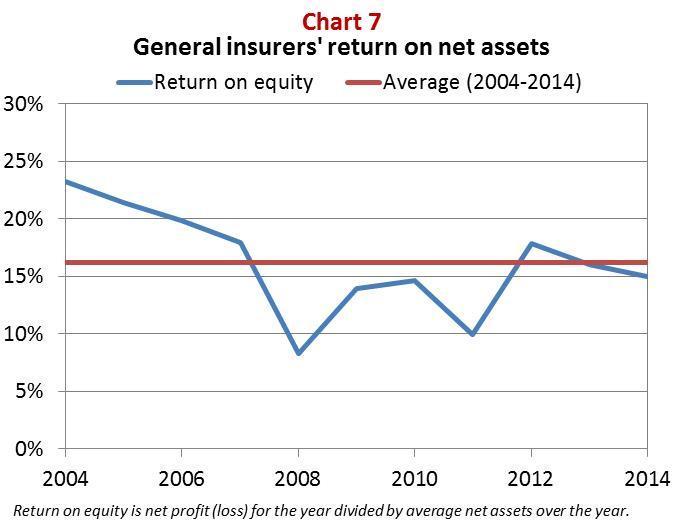

With that in mind, the Australian financial system looks in good health (Charts 6-8). The banking and insurance industries are making returns on equity of around 15 per cent, and rarely have these dipped below 10 per cent over the past decade, despite varying economic conditions and a strengthening of the regulatory framework. Current returns are not that far from the decade-long averages, although it is open to debate whether a safer financial system should be expected, or need, to generate the same returns that it did in the past.

Furthermore, material capital buffers, coupled with healthy returns on equity, do not suggest a set of regulatory capital requirements that are unduly constraining regulated institutions in their capacity to compete. Indeed, in housing lending, commercial insurance, and group life risk, we see evidence of quite aggressive competition – unfortunately, perhaps not alwys to the community’s long term benefit.

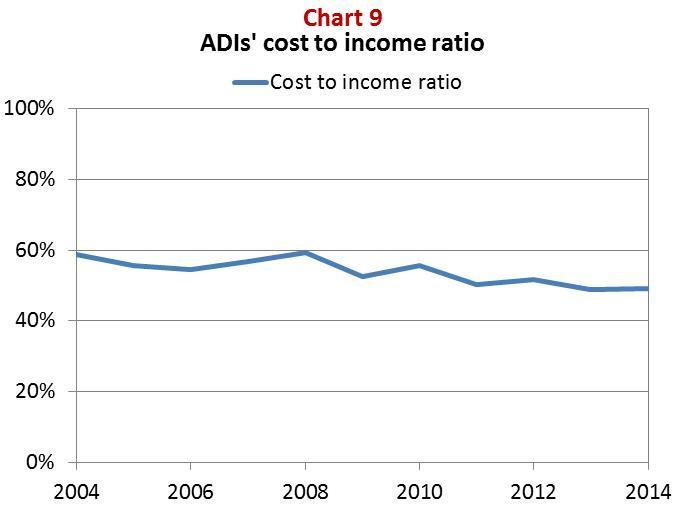

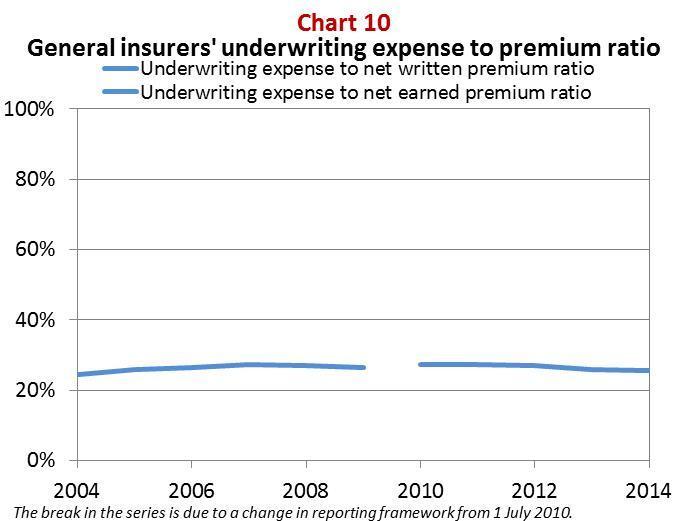

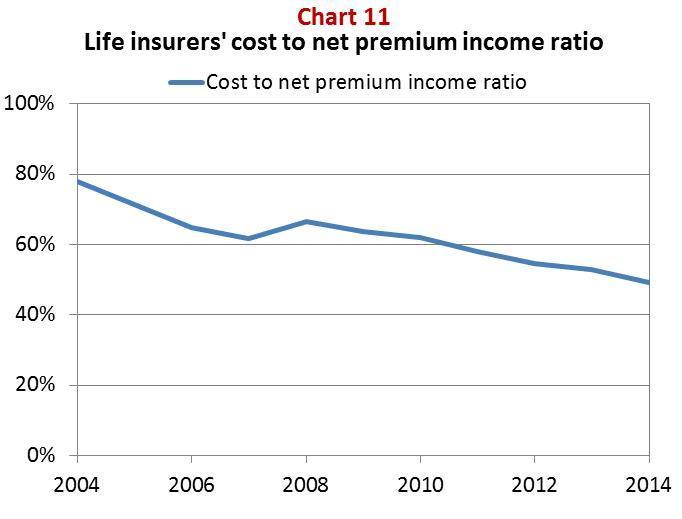

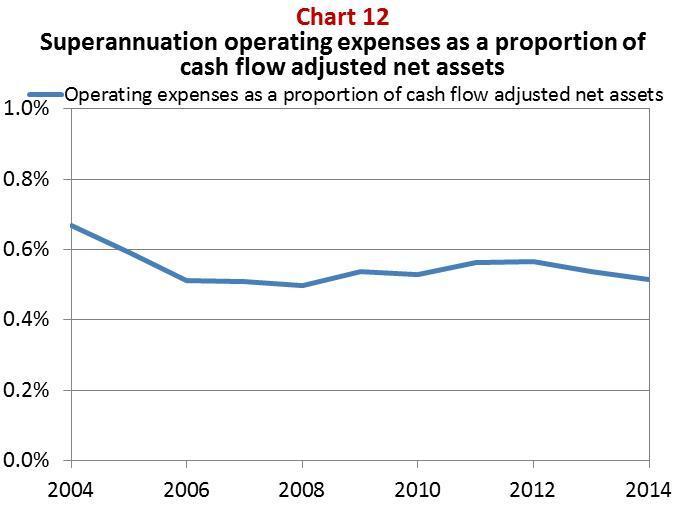

One means by which the financial system has maintained its returns while dealing with higher regulatory requirements is to improve its efficiency. In all industry sectors, there have been improvements in efficiency measures, albeit some more so than others (Charts 9-12). From APRA’s perspective, there is also little to suggest that regulatory reforms have materially impacted the longer term trends.

That the industry has become more efficient over time is not surprising. What is perhaps surprising is the lack of obvious link to the degree of consolidation in the industry over the past decade.

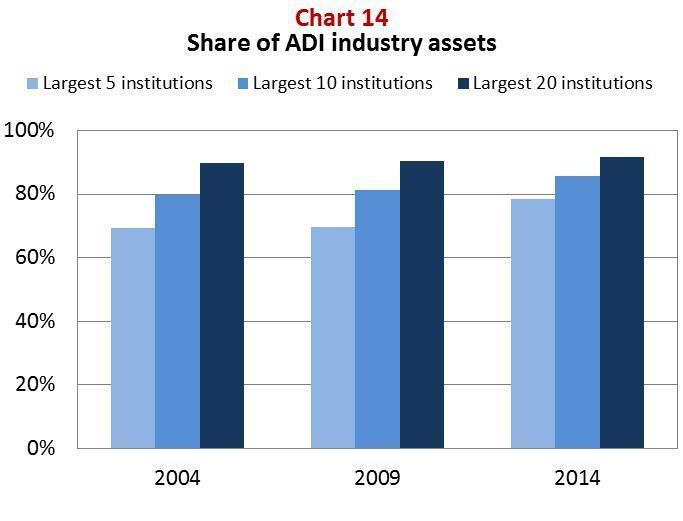

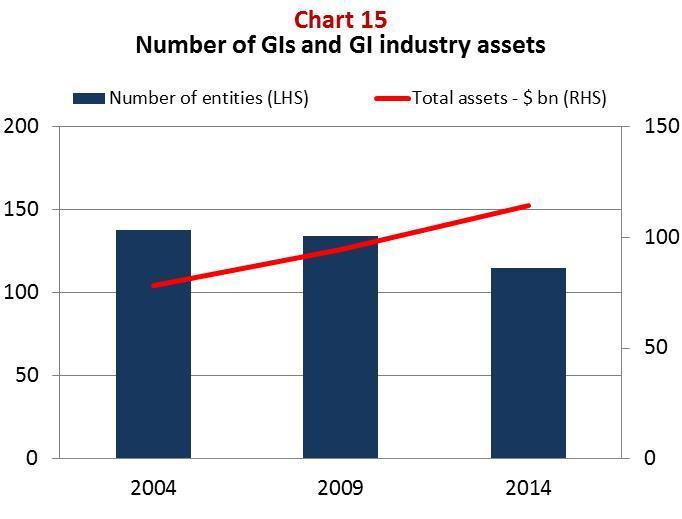

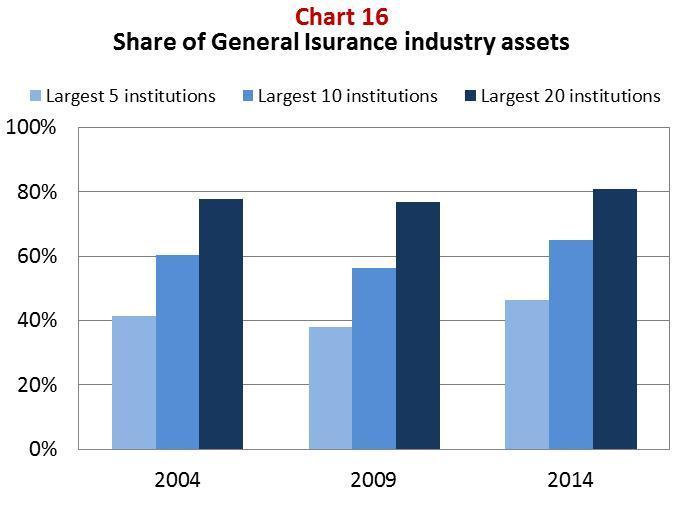

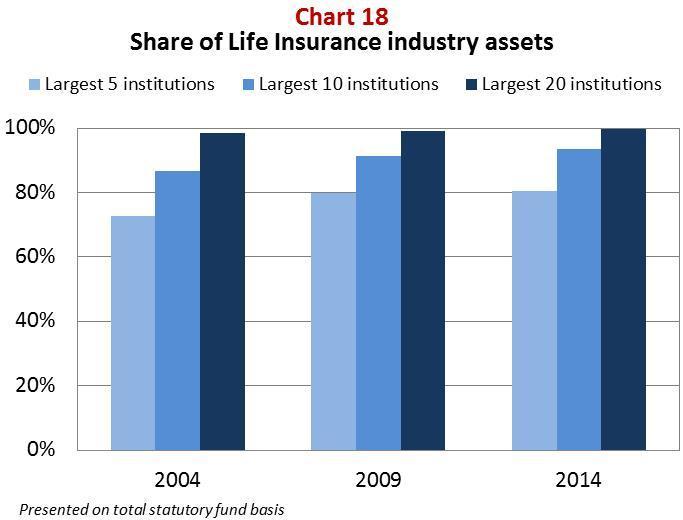

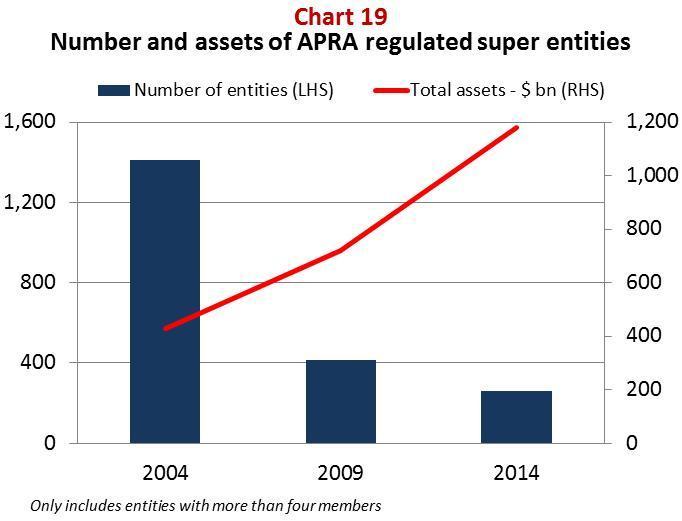

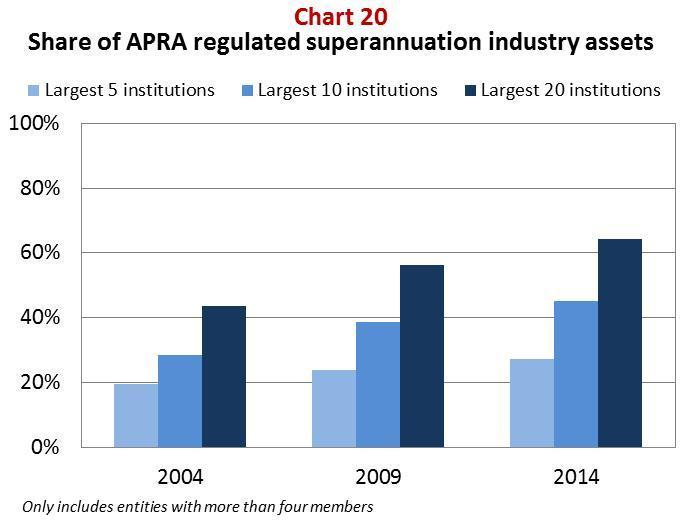

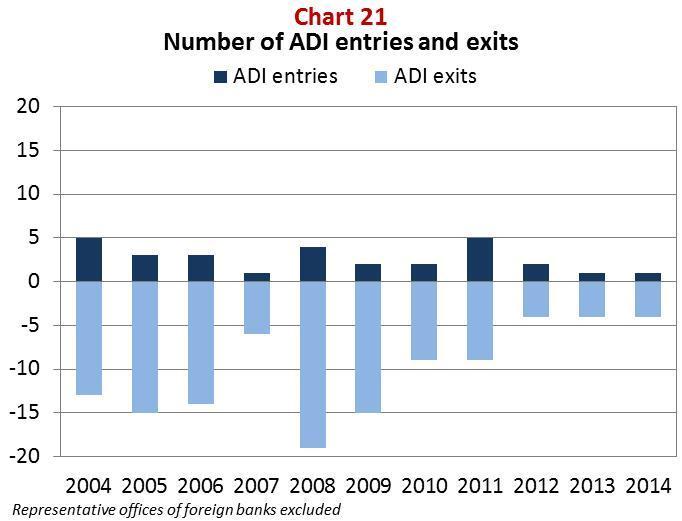

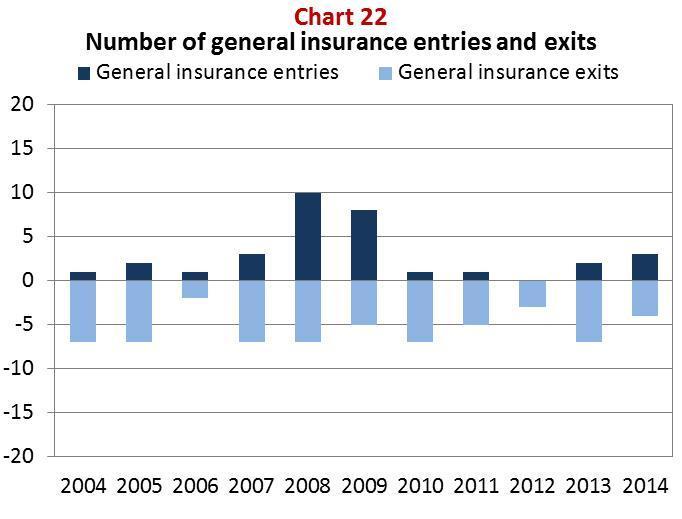

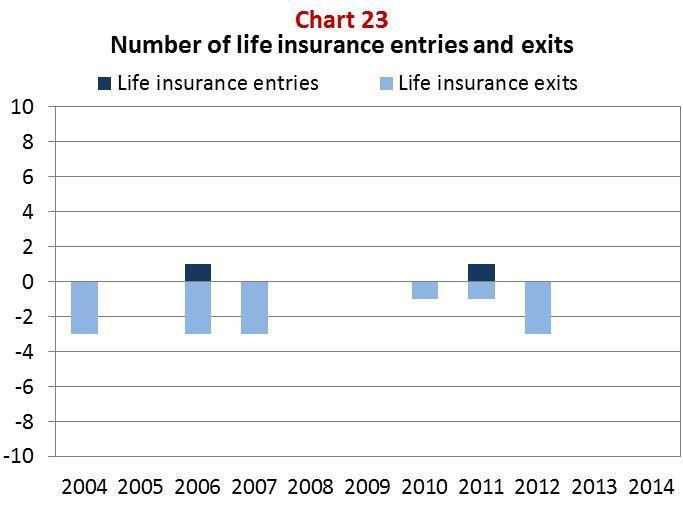

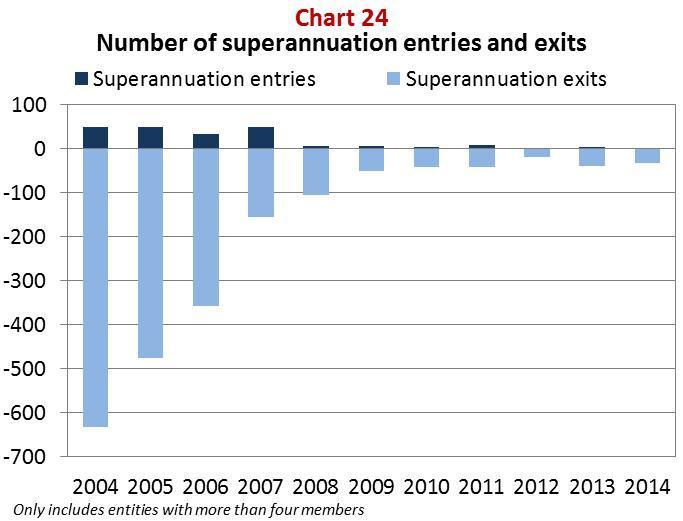

It is often noted Australia has a fairly concentrated financial system, and the past decade has only seen further consolidation across all industry sectors. In the case of superannuation, this has been the product of significant regulatory reform in the form of licensing and a general ‘lifting of the bar’ in prudential requirements, supplemented by the industry’s own on-going search for scale. In the case of ADIs, it is a mix of the continuous consolidation in the mutual sector, accompanied by the post-crisis retrenchment by foreign banks and consolidation within the regional sector. In the insurance industry, the reduced number of insurers has been driven, in part, by the consolidation of licenses within existing insurance groups, but there has also continued to be some genuine consolidation amongst industry participants. So while some part of this greater concentration is cyclical, much seems structural.

Although one argument for consolidation is that it generates economies of scale, it is not clear from the earlier charts that consolidation has been a significant driver of the efficiency improvements that we have seen. Improvements in efficiency have been just as evident in industries where there has been little consolidation as for industries where consolidation has been significant: at least at first glance, the benefits of increasing scale that consolidation should be generating are not always apparent. At least for superannuation, that will no doubt be a subject for further discussion later this morning.

While our financial system has tended to become more concentrated, both pre- and post-crisis, it has not been entirely one-way traffic. There has been a small but steady stream of new entrants to the APRA-regulated part of the financial system – albeit mainly in the ADI and general insurance sectors. Over the decade, many of the new entrants have been foreign-owned, and they have helpfully added competition, expertise and innovation to the financial system. Unfortunately, this pipeline has slowed somewhat in an environment in which many global institutions have scaled back their international aspirations while they repair their balance sheets. Hopefully we will see the number of new entrants start to pick up again over the coming years.

Nevertheless, the headline message is that the financial sector is more concentrated, and this brings me back to the importance of strong financial institutions.

Given consolidation and the strong growth in industry assets, we are supervising, and you are managing, much bigger and more complicated entities today than in the past. The end result of this consolidation is that the share of the financial system held by the largest financial institutions is as high as it has ever been.

Moreover, as the number of small entities has declined, the ‘average’ financial institution regulated by APRA is much larger than ever before:

- At the end of 2004, APRA regulated entities totalled around 1850, with aggregate assets of a little over $2 trillion, implying average assets per entity of $1.1 billion;

- At the end of 2014, there were a little under 600 entities with aggregate assets in the order of $5 trillion, implying an increase in average assets per entity of almost 8x in the space of a decade. This has been driven particularly by superannuation, where the change is even more stark: a multiple of almost 15x over the decade.

One implication of this evolution of the financial system is that the failure of the ‘average’ entity is likely to be more painful and destabilising than may have been the case a decade or so ago. That has implications not just for how APRA sets regulatory requirements, but how regulated institutions govern and manage themselves. I would like to offer a few thoughts on that point before I conclude.

The role for industry

As I noted earlier, the FSI has set us an interesting challenge: to make the financial system more resilient and more competitive.

The challenge does not, however, entirely belong in the hands of regulators. Industry participants have an important role to play. Critical to the setting of the regulatory framework is the extent to which financial institutions – large and small – can be relied upon to manage themselves with the long-run interests of all stakeholders in mind. Indeed, much financial regulation exists as a result of there being incentives for financial institutions to pursue strategies that are not necessarily in the wider community’s interests, because the externalities they impose do not have to be accounted for by their managers and shareholders.

As a result, three areas of heightened supervisory intensity in recent years have been governance, culture, and remuneration. The three go hand-in-hand, as all are critical to ensuring financial institutions conduct their business in a manner that avoids a repeat of the mistakes made in the lead-up to the financial crisis. For all the work that the public sector has done to reinforce the regulatory framework, we cannot hope to avoid a repeat of the underpricing of risk and misallocation of capital that occurred in the lead-up to the financial crisis if financial institutions do not also make changes to the way in which they manage themselves.

Ultimately, the shape of the regulatory framework, and the burden it imposes in the search for stability, will be a product of how regulated institutions choose to compete. They need to establish strong governance arrangements that allow board and senior management good oversight of the organisation’s operations, not just financially but also in terms of personal behaviours and culture. And a positive culture will best be encouraged when incentives require staff to compete by genuinely looking after the long term interests of customers. Available evidence suggests that there is further to go in this regard.

Concluding remarks

Much of the policy debate over recent years has been cast in terms of a trade-off between stability and competition in the financial system. We have never seen it that way, and were pleased that the FSI reached the same conclusion. Good regulatory settings can deliver financially strong competitors, creating both financial stability and a dynamic and innovative marketplace for financial services.

The generally strong capital positions, solid profitability, and improving efficiency evident in the Australian financial system do not suggest that financial institutions are unduly hindered by prudential regulation in Australia. That is not to say that policy settings cannot be improved to generate both more resilience and more competition, and the FSI has given us a roadmap by which we will pursue those objectives. But, critically, they do not require us to sacrifice one for the other.

Regulators like APRA will naturally have a strong focus on safety: that is what Parliament has tasked us to do. We can and do also play a role in encouraging sound competition, but first and foremost that will be driven by how financial institutions establish their own governance practices, culture and incentive structures. Strong governance, a culture of disciplined capital and risk management, and with rewards only for those who generate genuine risk-adjusted returns over the long term, will be critical for ensuring the benefits of competition can be harnessed in the interests of the community at large.

Footnotes

- Financial System Inquiry Final Report (December 2014), p.6.

- In addition, section 8A also requires APRA to have regard, and where possible avoid detriment, to financial system stability in New Zealand. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand, as that country’s prudential regulator, has a corresponding requirement with respect to financial stability in Australia.

- Financial System Inquiry Final Report (December 2015), p. xv.

- Independent Commission on Banking (September 2011), p.163.

- Ibid.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (October 2011), Bank Competition and Financial Stability, p9.

- Seeking Strength in Adversity, Speech to AB+F Randstad Leaders Lecture Series, 7 November 2014.

- Opening Statement to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, 20 March 2015.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.