A new(ish) tool in the toolkit

Pat Brennan, Executive General Manager, Policy and Advice Division - Actuaries Institute Banking Seminar, Sydney

Most people in this room would know well that the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision released a package of reforms in 2010 to promote a more resilient global banking system. That package is widely known as Basel III. Most would also know that the core of the Basel III package was strengthened capital requirements for the banking industry. Quite a number of you would also probably be aware that Basel III included the first global standards on liquidity and funding.[1] I suspect few, however, when asked to list the components of Basel III, would list the introduction of the first internationally agreed macroprudential tool. That tool is the countercyclical capital buffer, which aims to build capital buffers that can be used to protect the banking system from periods of excess credit growth.

The countercyclical capital buffer was incorporated into the Australian capital standards for banks and other authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) through Prudential Standard APS 110 Capital Adequacy (APS 110). The buffer came into effect from January 2016. It applies to all Australian ADIs as well as – via reciprocity provisions that I will say more about shortly – the Australian exposures of foreign banks operating in Australia.

Thus far, APRA has not used the countercyclical capital buffer in response to risks within the banking system. That does not mean we would never plan to do so. Today, I would like to recap how the countercyclical framework works, and outline the current trends that influence our thinking on its likely future use.

Objectives of the buffer

One of the lessons from the financial crisis was that losses incurred by banks following periods of excess growth in credit can be extremely large. As a result, there are several interrelated objectives of the countercyclical capital buffer:

- raising capital resilience when there is judged to be a build-up of systemic risk;

- moderating the cycle of credit growth and asset prices, through raising capital requirements during an upswing in credit demand. The increase in capital requirements may provide an incentive for banks to temper credit growth or raise the cost of credit to dampen demand; and

- improving the flow of credit during a downturn, thereby supporting the real economy, through the reduction of the buffer and corresponding release of the additional capital requirement in a period of stress. The release of the buffer requirement should alleviate pressure that may otherwise be on banks to improve capital ratios through constraining balance sheet growth, in turn helping to support the supply of credit for the economy.

In short, the countercyclical capital buffer provides a tool that can be used to raise banking sector capital requirements in periods of excess credit growth associated with the build-up of systemic risk. This additional buffer can then be released during periods of stress, to reduce the risk of the supply of credit being hindered by regulatory capital requirements.

Decisions on when to increase or decrease the countercyclical capital buffer are complex judgements, and involve an assessment of whether, and to what degree, there is excessive credit growth and rising systemic risk. APRA’s overall approach to setting the level of the buffer in Australia was set out in an Information Paper that we released in late 2015, along with the announcement that the initial setting of the buffer would be zero per cent. In that paper, we indicated that our decisions regarding the buffer would be based on forward-looking judgements, informed by a set of core indicators of systemic risk. These core indicators include the credit-to-GDP guide recommended by the Basel Committee, in addition to other indicators of systemic risk associated with the financial cycle. Importantly, we made clear that the countercyclical buffer would not be based on a mechanical formula, but rather a broader assessment of credit conditions. The primary indicators that we flagged are just that – indicators. By themselves, they are not determinative.

Broadly speaking, we said that decisions to increase the buffer would be based on an assessment of whether credit growth is excessive, asset price growth is unsustainable, and/or lending conditions are loose. Decisions to decrease or release the buffer would be informed by a reversal of these trends, and evidence of the emergence of financial stress. We also indicated that we would monitor and assess a range of core indicators to support judgements on the level of the buffer, in addition to other data, information and market intelligence. Given the potential broader implications for financial stability, APRA routinely seeks the counsel of other members of the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) as part of our decision-making process.

A key aspect of the countercyclical buffer framework is transparency. The Basel framework requires that the relevant authority – in Australia, that is APRA – publish at least annually a summary of the indicators that they are monitoring, and a rationale for their determination on the appropriate level of the buffer. This promotes not just accountability for the regulator, but also a deeper understanding amongst industry participants as to how such decisions are made – including how they can be better anticipated and planned for in advance. We have published our 2017 assessment today, and I would like to provide you with an overview of it this morning.

Operation of the buffer

Before I do, however, I would just like to remind you how the countercyclical buffer works.

First, the buffer can be set between zero and a maximum of 2.5 per cent of risk-weighted assets. In other words, it can be used to add up to an additional 2.5 per cent to existing capital requirements: for example, an ADI that normally faced a minimum CET1 requirement of 7 per cent could, if the countercyclical buffer was switched on in full, have to manage to a minimum requirement of 9.5 per cent.

The countercyclical capital buffer operates as an extension to the capital conservation range. ADIs that do not maintain their capital levels above the level of the conservation range have their dividend payments and other distributions increasingly restricted. The capital conservation range is typically set at 2.5 per cent, meaning that the countercyclical buffer could – if switched on in full – potentially see that range doubled, effectively encouraging banks to increase their capital levels to avoid encountering such restrictions.

An interesting aspect of the countercyclical capital buffer are the arrangements for international reciprocity. Normally, regulators set regulations for their jurisdictions, and these do not affect banks incorporated in other jurisdictions. In the case of the countercyclical buffer, however, APRA’s decisions may affect the capital requirements of non-Australian banks, and the decisions of our peers may affect the capital requirements of Australian banks.

The total countercyclical capital buffer that an ADI is required to hold reflects both the level of the Australian jurisdictional buffer applied to Australian exposures, and any buffer requirements in effect in other jurisdictions to which the ADI also has exposure. So when, as is the case now, the UK authorities decide to apply the countercyclical buffer to UK exposures, that decision also applies to the UK exposures of Australian ADIs. These international reciprocity arrangements are designed to ensure a level playing field between domestic and foreign banks with respect to countercyclical capital buffers across jurisdictions. For Australian ADIs, the buffer set by APRA will dominate the buffer calculation due to the weight of exposures. However, Australian ADIs with international exposures also need to monitor countercyclical capital buffers set by authorities in overseas jurisdictions in which they do business.

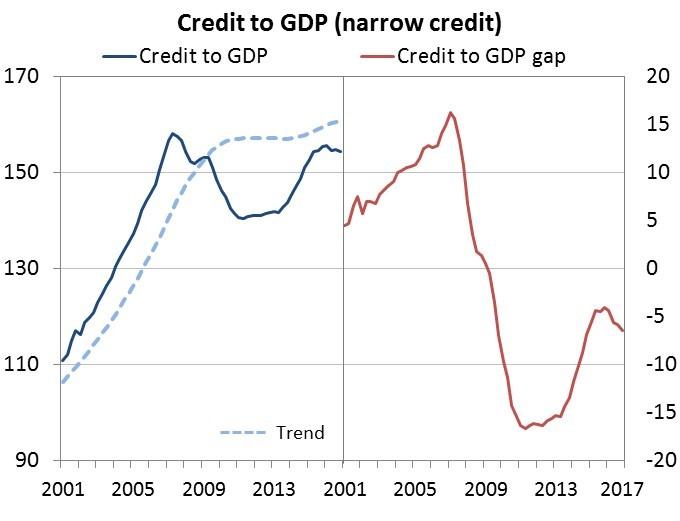

APRA’s indicator framework

To provide a foundation to the countercyclical buffer framework, the Basel Committee developed a common reference guide based on the aggregate private sector credit-to-GDP gap. The credit to-GDP gap is the difference between the ratio of credit-to-GDP and its long term trend; a positive gap (i.e. a level above trend) is potentially indicative of excessive credit growth. The Basel Committee recommended that the credit-to-GDP guide should be considered as a starting reference point, but that relevant authorities could also use judgement and other relevant indicators in setting the countercyclical capital buffer in their jurisdiction.

Few, if any, jurisdictions have chosen to rely on the credit-to-GDP gap alone in establishing their countercyclical capital buffer. Most, like APRA, have selected a range of metrics that are most relevant for local market conditions. This has included evaluating indicators that would have provided strong signals of excess credit growth and rising systemic risk during previous financial cycles, for example, the pre-financial crisis period of the early 2000s.

As a result, APRA adopted an approach that is:

- informed by a target set of core indicators of systemic risks associated with the financial cycle;

- judgement-based, with a strong weight placed on the analysis and assessment of indicators, rather than on mechanical triggers; and

- forward-looking, based on early warning indicators during the risk build-up phase, to allow time for changes to ADI capital levels to be implemented, and on timely indicators of stress to enable a quick release of requirements during a downturn.

As the foundation of its countercyclical capital buffer framework, APRA chose nine core indicators that are well understood and generally publicly available, relevant and representative of the risks of concern. These are:

- credit growth indicators: credit-to-GDP gap, housing credit growth and business credit growth;

- asset prices: housing price growth and commercial property price growth;

- lending indicators: higher-risk residential mortgage lending, business lending conditions, and loan pricing and margins; and

- financial stress: non-performing loans.

While the core indicators provide a signal on the direction of systemic risk, as I noted they will not translate formulaically into decisions on the level of the buffer. To understand the reasons for movements in these indicators, APRA monitors a wide range of supplementary metrics and other data, including sub-segments and more granular data. Other factors will also be important in this decision, including an assessment of current bank capital positions, prudential concerns and the economic outlook. APRA also considers findings and trends arising from its supervisory activities involving individual regulated institutions where relevant. And, as I noted, we are also guided by the views of other members of the CFR.

APRA assesses each of the above indicator areas individually and as a group, together with other relevant information, on a quarterly basis to arrive at an overall view of the degree of concern with respect to a build-up of systemic risk.

Current trends

As I noted, we originally set the countercyclical buffer at zero per cent at the end of 2015, noting that notwithstanding strong credit growth into housing, there was little to suggest excessive credit growth across the Australian economy more broadly.

So what do current trends show?

Credit growth

The Basel Committee framework suggested that authorities should consider use of the countercyclical capital buffer if the credit-to-GDP gap rose above 2 per cent. In Australia, the credit-GDP gap has been negative for some time, and was -6.4 as at end September 2017. With the recent moderation in housing lending growth, the gap is expected to remain negative for some time yet.

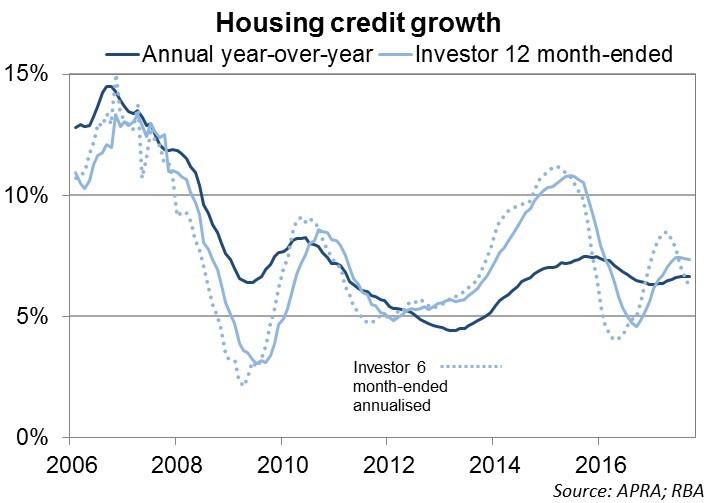

At a more granular level, housing investor credit growth has shown signs of a pick-up over the past 12 months, but growth moderated slightly over the September quarter. Forward-looking indicators suggest this moderation will likely continue in the months ahead. More broadly, total housing credit growth has been little changed, as the moderation in investor credit has been offset by stronger growth in owner-occupied credit. This trend is reflective of a recent widening in differential pricing between the two products in response to regulatory interventions. Growth in credit is expected to be supported in the near term by, amongst other things, the settlement of a significant supply of apartments due to hit the market in the eastern capital cities in the coming months. However, working in the other direction is the impact of higher home loan rates and tighter lending standards, which may see some marginal borrowers finding it more difficult to access credit, particularly for investor and interest-only products.

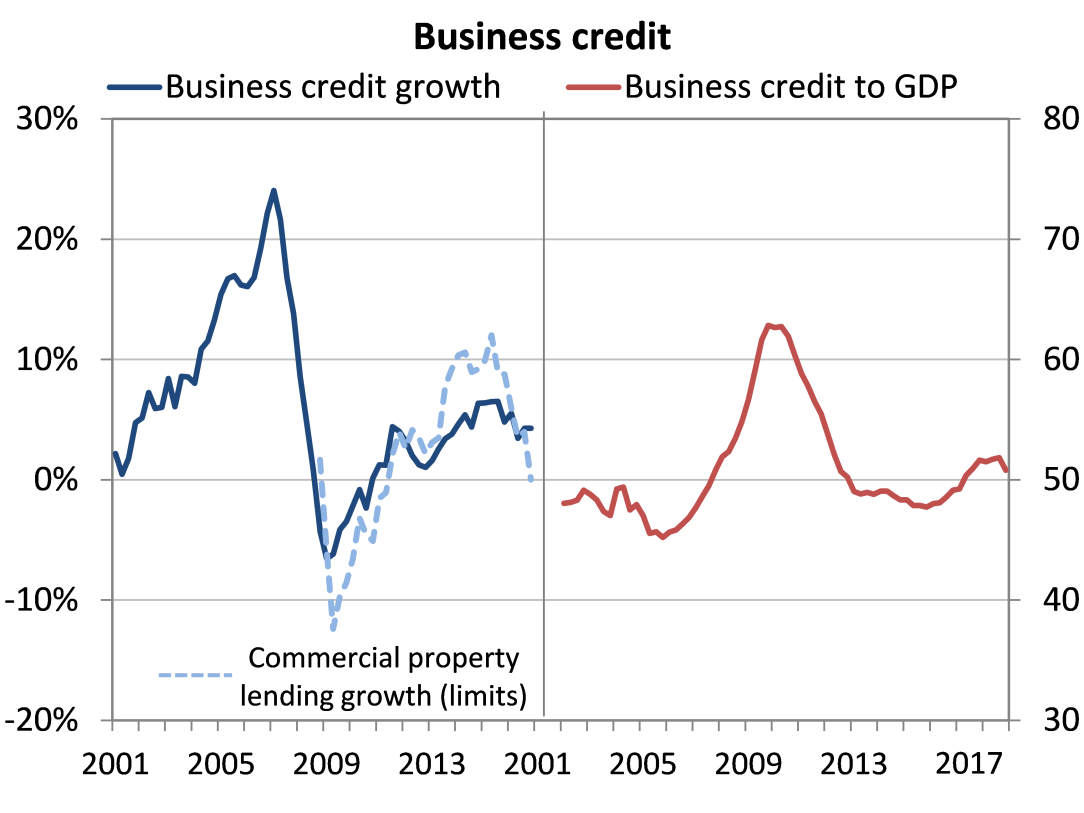

Business credit growth strengthened slightly over the September quarter, following slower growth earlier in the year. However, business credit growth remains below recent mid-2016 peaks, and relatively modest overall. Looking ahead, quarterly and six-monthly annualised growth rates suggest that business credit growth may strengthen gradually in the near-term. Survey-based measures support this prognosis, suggesting that both business confidence and conditions have continued to strengthen over the past year.

Domestic ADIs have also reduced their exposure limits to commercial property, consistent with a tightening in lending standards, particularly for residential developments. Growth in commercial property lending exposures reduced slightly over September.

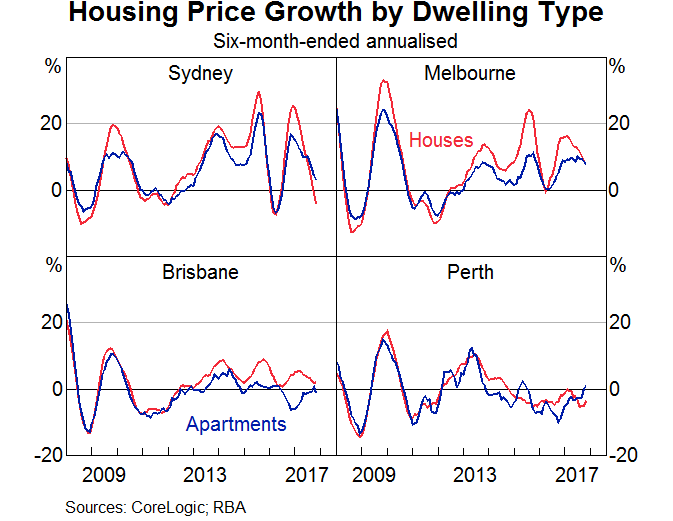

Asset prices

Housing market conditions continue to vary greatly across the country, but have generally eased in recent months. While measures of annual price growth remains well above long-run averages, more recently housing price growth has slowed in pace, particularly in the Sydney market. Nationally, six month-ended annualised growth has slowed to less than half that of recent peaks, influenced by APRA’s benchmark on interest-only lending, increased housing supply and higher interest rates for some borrowers.

Price growth in housing assets also continues to differ by asset type. At a national level, apartment prices continue to be outpaced by price growth of detached houses, reflecting the increased relative supply of apartments. However the gap in price growth by housing type has begun to narrow, as elevated price growth in detached housing falls back in line with that of apartments.

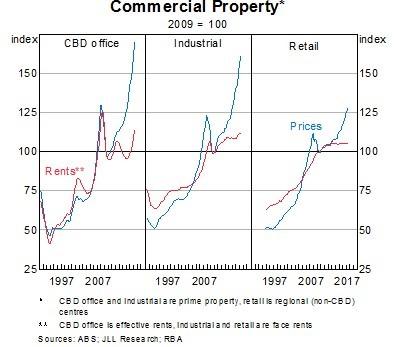

Commercial property price growth, however, remains significant. Growth in Australian commercial property asset prices continued to accelerate rapidly over the September quarter. While rapid growth in CBD office prices was supported by similar growth in rents, growth in Industrial and Retail asset prices continued to greatly outpace growth in rents over the quarter. Six-month ended annualised price growth rates were slightly lower than annual rates for non-residential commercial property in September, suggesting price growth may soften somewhat in coming months. Results from APRA’s commercial property data analysis and survey of credit conditions and lending standards suggest that underwriting standards have broadly improved, particularly with respect to loan sizes (relative to valuations and costs) and minimum presales requirements.

Lending conditions

At an industry level, shares of higher-risk mortgage lending continued to moderate over the September quarter. Shares of new lending written on interest-only terms further declined, particularly for investor lending. A sharp decline in approvals data suggests that interest-only lending will further decline in the months ahead. ADIs have also generally revised lending standards to accord with APRA’s expectations for high LVR interest-only lending. These revisions have begun to flow through to lower shares of high LVR interest-only lending.

The total stock of interest-only loans on ADIs’ books has declined in recent months, consistent with the incentive for existing customers to switch to cheaper principal-and-interest repayments. Upwards repricing has also seen investor lending continue to moderate to be comfortably within APRA’s 10 per cent benchmark. However, the share of loans written at high LTIs (>6x) ticked up slightly over the September quarter, and loans approved with a relatively low net income surplus remain quite high.

Recent lending conditions appear to have been largely unchanged in the corporate and SME sectors. NAB’s survey of business confidence suggests that confidence and conditions had remained strong over the September quarter and are well above long-run averages. However, in feedback to APRA on credit conditions and lending standards, banks reported that overall demand remains largely subdued. Consequently, limited growth opportunities in these sectors create competitive pressures, placing continued pressure on lending standards.

For commercial real estate lending, standards have continued to tighten amid concerns of oversupply and heightened settlement risks in some regions. In particular, some banks noted a tightening of maximum loan-to-valuation ratios for both development and investment lending, consistent with rapid growth in asset prices. Banks also reported a tightening in minimum presales requirements and minimum interest coverage ratios.

While the peak of apartment supply is yet to come, banks reported that settlement failures are in line with historical norms. However, some banks have noted that settlement delays have become more prominent, consistent with (often foreign) purchasers finding it more difficult to secure retail funding. Although not yet evident in the data, banks continue to expect credit quality to deteriorate for commercial real estate, particularly for development and retail investment lending.

Impaired and past-due assets

Non-performing loans are one indicator, albeit lagged, of realised financial stress. The overall share of non-performing loans remains near its post-crisis low, at a little under 1 per cent of lending. That said, there are ongoing divergences in loan performance by region and asset type. Over the September quarter, higher arrears on housing and personal lending persisted in regions and sectors with exposures to mining, with reported arrears on personal loans further affected by changes in banks’ hardship reporting. In contrast, the low interest rate environment continues to support credit quality in the commercial real estate sector and other business sectors.

APRA’s current assessment

Bringing these various considerations together is, as I said earlier, inevitably a matter of judgement. We have concluded that there is not a case, at this stage, to apply a non-zero countercyclical capital buffer, all things considered. Broadly speaking, the credit-to-GDP ratio is well below its longer-term trend and credit growth indicators are currently showing some signs of softening, higher risk lending for both residential and commercial property is being reduced, and impaired assets are, overall, at modest levels. Most of these indicators are flat, or tending to indicate lower risk, over the most recent quarter. Most are also indicating a moderation in risk since APRA’s original decision in late 2015.

On the other hand, trends in property prices have been signalling heightened risks for some time. On their own, however, they do not suggest the need to institute the countercyclical buffer at this point. Rather, APRA has chosen to tackle these risks with other tools. In housing lending, this includes our benchmarks on investor and interest-only lending, as well as substantial supervisory work to improve serviceability standards. APRA has also conducted a thematic review on commercial property lending, and has communicated the key areas for improvement to the industry.[4]

That said, as I noted to begin with, the countercyclical capital buffer is designed to reinforce the resilience of the banking system in response to excessive credit growth. Certainly credit growth has been a key factor in our supervisory concerns in relation to housing. But ultimately we decided not to use the countercyclical buffer for housing-related risks thus far because:

- the risks we were responding to could be better addressed, in our view, with more targeted measures aimed at improving credit underwriting practices and targeting capital increases specifically to mortgage lending;

- we were already building capital in the banking system via the ‘unquestionably strong’ and mortgage risk weight recommendations of the Financial System Inquiry, which were being implemented in parallel; and

- we did not see a need to apply a broad-brush capital increase that would impact the provision of non-housing credit.

If, however, we got to the point where credit was deemed to be growing excessively despite the establishment of strong credit standards, then we may well be in the environment in which the CCyB is designed to be used. Our judgement, as of today however, is that we are not at that point and other tools are working more effectively.

Concluding remarks

Let me quickly sum up.

Basel III brought with it the first internationally agreed macroprudential tool in the form of the countercyclical capital buffer. The buffer is available to be used at times when credit growth is excessive, with a view to building additional resilience in the banking system. In simple terms, this can be thought of as putting a little bit extra away for a rainy day.

In Australia, the countercyclical capital buffer has not been used: it is thus far a new and unused tool in our toolkit. We have not used it so far because we feel the risks to the stability of the banking system can be dealt with through a range of other tools available to us. In the case of housing, where there has been most supervisory attention, we think it far better to tackle loose lending standards directly, rather than simply tolerate them and require more capital instead.

Footnotes

- These are the Liquidity Coverage Ratio and the Net Stable Funding Ratio. In Australia, the LCR has been in place since 2015, and the NSFR comes into effect from the beginning of 2018.

- APRA Letter to all ADIs: Commercial property lending - Thematic review observations (7 March 2017).

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.