Cost recovery implementation statement 2025

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose

This Cost Recovery Implementation Statement (CRIS) provides information on how the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) implements cost recovery for the supervision of financial institutions1 and APRA’s licensing and authorisation charging activities. These charging activities were reviewed as part of Treasury portfolio charging reviews in 2016-172 and 2021-22. No changes to the current levy methodology were made following those reviews.

This CRIS is prepared in line with the Australian Government Cost Recovery Guidelines (the CRGs) under the Australian Government Charging Framework, and demonstrates consistency, transparency and accountability of cost recovered activities and promotes the efficient allocation of resources.

1.2 Background

APRA is the prudential regulator of the Australian financial services industry. It oversees Australia’s banks, credit unions, building societies, general insurers, life insurers, private health insurers, reinsurers, friendly societies and most of the superannuation industry. APRA is primarily funded by the industries that it supervises. APRA currently supervises financial institutions holding approximately $9.5 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.

APRA works closely with other regulatory agencies to achieve its purpose and strategic priorities including those that form part of the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR), which includes the Department of the Treasury (the Treasury), the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). Key activities 2024-25 are captured within APRA’s Corporate Plan available on its website.3

1.2.1 Government policy objectives and outcomes for APRA

APRA’s policy objectives are set out in its enabling legislation and in various industry Acts. Broadly speaking, APRA’s objectives are focused on three core outcomes:

- ensuring the financial institutions it supervises are resilient and prudently managed;

- promoting a stable, efficient, and competitive financial system; and

- contributing to the Australian community’s ability to achieve good financial outcomes, working in close partnership with key stakeholders including Government, regulatory agencies and industry.

APRA’s outcome statement as published in its Portfolio Budget Statement outlines the intended results, impacts or consequences of actions for the Australian community as:

“enhanced public confidence in Australia’s financial institutions through a framework of prudential regulation which balances financial safety and efficiency, competition, contestability and competitive neutrality and, in balancing these objectives, promotes financial system stability in Australia”.

1.2.2 Description of APRA’s cost base

APRA’s cost base comprises the following:

Table 1: APRA’s cost base

| Cost base | 2020-21 Actual ($m) | 2021-22 Actual ($m) | 2022-23 Actual ($m) | 2023-24 Actual ($m) | 2024-25 Forecast ($m) | 2025-26 Budget ($m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee benefits | 142.8 | 153.5 | 157.6 | 165.9 | 187.4 | 194.8 |

| Supplier expenses | 34.1 | 36.9 | 46.4 | 44.0 | 63.9 | 51.4 |

| Depreciation and amortisation | 18.6 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 26.4 | 20.3 | 20.6 |

| Other costs | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 2.0 |

| Total expenses | 196.4 | 214.6 | 229.3 | 237.0 | 273.1 | 268.8 |

The increase in APRA’s cost base from 2020-21 onwards reflects additional funding since the 2020 Federal Budget. Some key funding components include:

- During 2020-21 (also impacting 2021-22), APRA’s funding was increased temporarily to respond to the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) through the measure “Treasury Portfolio – additional funding”.

- For 2022-23, APRA’s funding increased to maintain its capacity to respond to risks within the financial system.

- The increase in APRA’s funding for 2023-24 relates primarily to a recovery of under-collected levies from

2022-23 and the Government’s revision of the Wage Cost Index indexation.

- For 2024-25, APRA’s funding increased through the measures “Cyber Security of Regulators and Improving Registers” and “Climate Related Financial Disclosures”.

- For 2025-26, APRA’s funding decreased slightly, driven by the tapering of the “Cyber Security of Regulators and Improving Registers” and “Climate Related Financial Disclosures”.

These measures increased APRA’s available resources, including APRA’s overall staffing level4, and other costs.

Employee benefits are the largest proportion of APRA’s cost base, ranging between 68 per cent and 73 per cent of the total cost base from 2020-21 to 2025-26. These costs comprise: staff salaries, superannuation, performance bonuses5, leave provisions and other employee-related costs.

Supplier expenses are the second-largest component of APRA’s cost base, ranging between 17 per cent and 24 per cent of the total cost base from 2020-21 to 2025-26. These costs comprise: property and office expenses, IT costs, training and conference expenditure, travel, and contractor and professional services costs.

Depreciation and amortisation costs ranged between 7 per cent and 11 per cent of the total cost base from 2020-21 to 2025-26, increasing primarily due to the introduction of a new Accounting Standard6 as well as reflecting an increase in APRA’s fixed and intangible assets, which include property fit outs and IT systems development expenditure.

1.2.3 Description of activities that are recovered by levies or charges

APRA's activities fall into four main categories:

- establishing prudential standards to be observed by supervised institutions (levy recovery);

- assessing new licence applications (licensing charge recovery);

- assessing the safety and soundness of supervised institutions (levy recovery); and

- where necessary, carrying out APRA’s resolution authority responsibilities or other remediation, crisis response and enforcement activities (levy recovery).

In addition, APRA:

- provides statistical information to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (fee-for-service charge recovery);

- accredits banks to use internal models to meet capital adequacy requirements under the Basel Framework (fee-for-service charge recovery); and

- administers the National Claims and Policies Database (NCPD) for general insurers (levy recovery).

For revenue collected on behalf of other Commonwealth entities, refer to section 1.2.6.

1.2.4 Institutions liable to pay levies or charges

The relevant institutions are:

- Authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) comprising banks, building societies and credit unions;

- Life insurance companies (LIs), comprising life insurance companies and friendly societies;

- General insurance and reinsurance companies (GIs);

- Private health insurers (PHIs); and

- Superannuation entities, excluding self-managed superannuation funds (Super).

1.2.5 Private health insurance regulation by APRA

APRA assumed responsibility for the prudential supervision of private health insurers from 1 July 2015. There are currently 30 registered PHIs. In addition to supervisory responsibility for these insurers, APRA administers the following three PHI charges:

- Supervisory Levy – to fund APRA’s day-to-day regulatory activities;

- Risk Equalisation Levy (REL) – to ensure that no PHI is unduly impacted by costly claims because of the profile of their policyholders, the Private Health Insurance (Risk Equalisation Levy) Act 2003 provides that the cost of certain types of expensive claims should be pooled and shared amongst all health benefits funds; and

- Collapsed Insurer Levy (CIL) – following approval by the Minister for Health, a levy may be raised against PHIs to help meet a collapsed private health insurer’s liabilities to those insured under its policies which the insurer is unable to meet.

This CRIS only relates to the imposition of the supervisory levy for private health insurers as the REL and CIL are not subject to the CRGs.7 The supervisory levy formula for 2025-26 is set by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Supervisory Levies Determination 2025. The PHI aggregate number of single and non-single (i.e. joint) coverage policies issued by all private health insurers on the annual Census day8is used as the formula base.

1.2.6 Revenue collection on behalf of other government agencies

Under s50(1) of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 (APRA Act), APRA is authorised to collect revenue to offset expenses incurred by certain other Commonwealth entities, including Treasury, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), and the Gateway Network Governance Body Ltd (GNGB). These expenses relate to:

- costs to administer the Compassionate Release of Super program, as well as the Superannuation Lost Member Register and Unclaimed Superannuation Money frameworks (ATO);

- administer a grant to fund the superannuation consumer advocate (Treasury); and

- governing and maintaining the superannuation transactions network (GNGB).

1.3 Charging activities not subject to the Cost Recovery Guidelines

1.3.1 Financial Claims Scheme levies

APRA has responsibility for administering the Financial Claims Scheme (FCS). The FCS is an Australian Government scheme that provides protection (subject to a limit) of deposits in banks, building societies and credit unions, and of policies with general insurers in the unlikely event that one of these financial institutions fails.9

Under the Financial System Legislation Amendment (Financial Claims Scheme and other measures) Act 2008 the relevant Minister, on activation of an FCS event, makes a declaration under either the Banking Act 1959 or Insurance Act 1973. In the case that funds recouped following the liquidation process are not sufficient to cover the outstanding depositor/policyholder claims of a failed entity, each entity within the relevant industry may be charged an FCS levy to recoup the shortfall.

An FCS levy is not subject to the CRGs. The only time the FCS has been activated to date has been for the recovery of funds relating to the failed general insurer Australian Family Assurance Limited in 2010.

2. Policy and statutory authority to recover costs

2.1 Government policy approval for cost recovery

APRA commenced operations on 1 July 1998. In establishing APRA, the Government determined that APRA’s operations would be fully cost recovered through levies on the institutions that it regulates. Today, this occurs under the Australian Government Charging Framework (incorporating the CRGs), which broadly states that the cost of regulation should be met by those institutions that create the need for it. While the Government also provided authority for APRA to charge for direct services (such as licences), the majority of APRA’s supervision costs were to be met through annual financial institutions supervisory levies.

APRA’s activities are considered appropriate for cost recovery as they meet the following criteria:

- they are of a regulatory nature;

- there is an identifiable group of institutions, which are not part of the Government sector, that directly use or are the subject of the activities;

- it is practical and efficient to undertake the activities on a cost recovery basis; and

- cost recovery is not inconsistent with the Government’s policy objectives outlined above.

Annually APRA’s Portfolio Budget Statement (PBS) is tabled in Parliament.

2.2 Statutory authority to impose cost recovery charges

The legislative framework for levies is established by the Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies Collection Act 1998, which prescribes the timing of payment and the collection of levies. A suite of imposition Acts imposes levies on regulated institutions. These Acts are the:

- Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998;

- Authorised Non-operating Holding Companies Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998;

- Life Insurance Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998;

- General Insurance Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998;

- Superannuation Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998;

- Retirement Savings Account Providers Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 1998; and

- Private Health Insurance Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 2015.

These Acts impose levies on regulated institutions. In some instances, they set a statutory upper limit and provide for the Minister to make a determination as to certain matters, such as levy percentages for the restricted and unrestricted levy components, maximum and minimum levy amounts applicable to the restricted levy component, and the date at which an entity’s levy base is to be calculated.10

Links to the current Determination:

- Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions and Authorised Non-Operating Holding Companies: Fees and levies for authorised deposit-taking institutions

- General Insurers and Authorised Non-Operating Holding Companies: Fees and levies for general insurers

- Life Insurers and Authorised Non-Operating Holding Companies: Fees and levies for life insurers and friendly societies

- Superannuation and Retirements Savings Account Providers: Fees and levies for superannuation

- Private Health Insurance: Fees and levies for private health insurers

In respect of applications or requests made to APRA, paragraph 51(1)(b) of the APRA Act permits APRA, by legislative instrument, to fix such charges. Subsection 51(2) of the APRA Act provides that a charge fixed under subsection 51(1) must be reasonably related to the costs and expenses incurred or to be incurred in relation to the matters to which the charge relates and must not be such as to amount to taxation. The Government has also provided authority to APRA to recover other specific costs incurred by certain Commonwealth agencies and departments. The Minister’s determination in this regard, under the APRA Act, is to recover the costs on behalf of other government agencies as indicated in section 1.2.6.

3. Cost recovery model

3.1 Outputs and business processes

The budgeted cost base for APRA is refined over the forward estimates to reflect relevant Government funding decisions. The forward estimates, and in particular the budget for the upcoming year, are usually finalised in May each year and presented in the annual PBS.

The cost base is supported by associated income streams, the largest element being appropriation revenue. The largest component of the appropriation revenue is the amount to be collected from the financial industry by annual levies, with other components being the separately collected NCPD levy and other smaller government appropriations. Smaller components of the cost-base include recoveries for licensing/authorisation charges and fees for services charges (refer to section 3.4 and 3.5 for details).

Once the cost base is finalised, and the corresponding sources of funds identified, a forecast of any levy income over- or under-collected in the current year is made. Any over-collection in a year is returned to industry in the following year, and vice-versa for under-collections.

Upon identification of the total amount to be recovered each year by industry levies, the amount is allocated to APRA’s regulated industries for collection.

A key input in APRA’s cost recovery methodology is the estimated time spent on supervising each industry, which is derived from APRA’s internal time management system.

The budgeted funding level included in the PBS defines the financial resources that APRA has available to support its on-going operations each year. Although under/over-collections of levies are recouped from/returned to industry each year as described above, expense underspends and overspends impact APRA’s financial reserves. APRA monitors reserve levels to ensure they remain within appropriate tolerances and undesired build-ups or reductions are avoided.

3.2 Costs of APRA’s activities

APRA has powers to establish prudential standards, and other components of the prudential framework, that are aimed at maintaining the safety and soundness of the institutions that APRA regulates. APRA’s standards set out minimum capital, governance and risk management requirements. Prudential Practice Guides provide direction on how institutions may adhere to these prudential standards, as well as to other related expectations.

APRA’s prudential policies and supervision activities support its purpose to ensure the financial interests of Australians are protected and the financial system is stable, competitive and efficient.

3.2.1 Financial soundness of supervised institutions

Once licensed, an institution is subject to ongoing supervision to ensure that it is managing its risks prudently and meeting prudential requirements. APRA follows a risk-based approach where institutions facing greater risks receive closer supervision. This enables APRA to deploy its resources in a targeted and cost-effective manner.

APRA supervisors perform a range of supervisory activities to identify and respond to risks. Such activities are undertaken by supervisors with in-depth knowledge of institutions in a particular sector and are supported by risk and data analysis specialists.

Prudential engagements

Supervisors engage regularly with institutions to discuss and resolve issues of concern. A common activity is the “prudential review” – where APRA supervisors engage with an institution, targeting one or more risk areas to assess the effectiveness of the institution's risk management framework, including its internal governance processes at a more in-depth level. Supervisors also meet regularly with boards, senior management, risk and operational staff on specific matters and engage where necessary with key advisers, including auditors and actuaries.

Analysis

Financial and non-financial analysis is also an important supervisory tool to assess the strength of an institution at an industry, peer and entity level. Such analytics are based on data and information submitted by the institutions and includes stress testing, capital and scenario analysis.

Domestic and international regulator liaison

APRA is part of a domestic and global regulatory community and collaborates with peer regulators to share information and insights across a range of topics. APRA contributes to and participates in a variety of global standard setting regulatory bodies in relation to policy and supervision.

Risk assessment and supervisory outcomes

APRA’s Supervision Risk and Intensity (SRI) Model is designed to enable supervisors to:

- make robust and timely risk assessments of a regulated entity; and

- develop appropriate supervision strategies and plans to address the level of risk.

The SRI Model captures the level of prudential risk within APRA-regulated entities across a number of risk categories and helps focus APRA’s resources to the entities of greater risk. Prudential risks include financial, operational and behavioural risks that could have an adverse impact on the outcomes for bank depositors, insurance policyholders and superannuation members, or the broader financial system.

The SRI Model has three core components:

- Tiering – an entity’s tier reflects the potential impact that entity failure, imprudent behaviour or operational disruptions could have on financial stability, economic activity and the welfare of the Australian community. An entity’s tiering is critical in determining the level of routine supervisory attention that is required to ensure adequate identification of risks and follow up of actions;

- Risk assessment – within a given tier, different entities will operate with different levels of risk. The assessment and rating of key risk categories provides a consistent approach for assessing an entity’s overall risk profile. While the categories provide a level of consistency across all entities and industries, the SRI model incorporates industry nuances and provides flexibility for capturing emerging risks; and

- Staging – the outcome of the ratings in the risk assessment will be an overall supervisory stage for the entity. This staging will impact APRA’s overall supervision strategies and actions and require APRA’s supervisors to consider the appropriate use of APRA’s powers and tools.

3.2.2 Remediation, crisis response and enforcement

APRA has substantial legal powers that enable it to intervene where there is a threat that an institution may not be able to meet its obligations to its depositors, insurance policyholders or superannuation fund members. APRA will also intervene where there is a threat to the stability of the financial system. In these contexts, APRA has the power to conduct investigations of supervised institutions and, in some cases, to give them directions of a wide-ranging nature in addition to other powers in its role as a resolution authority.

3.3 Design of APRA’s supervisory levy and direct user charges

3.3.1 Supervisory levy

APRA uses two methodologies to calculate supervisory levies. The first levy methodology is applied to the ADI, superannuation, GI and LI industries. It has two components:

- the restricted levy component, which has a cost-of-supervision based rationale and is structured as a percentage rate on assets subject to minimum and maximum amounts; and

- the unrestricted levy component, which has a systemic impact and vertical equity rationale, and is structured as a percentage rate on assets, without a minimum or maximum amount for individual regulated institutions.

The levy allocation methodology is designed to fully recover the costs from each industry and minimise cross-subsidisation between industries.

To reduce the volatility in levies charged to industry, APRA smooths the allocation of costs, through the use of a moving four-year average, when calculating the percentage of time split between the restricted and unrestricted levy components, before subsequent allocation to the four industries.

Once the amount to be recovered from the four industries in both the restricted and unrestricted components is known, and the population estimated, the required levy rates to recover these amounts are then calculated.

The second levy methodology used is applied to the PHI industry and is a fixed price levy. This levy adopts a cost-of-supervision based rationale and is structured as a fee per policyholder. There are no minimum or maximum amounts.

Table 2: Private health insurance (PHI) levy 11

| Private health insurance | 2022-23 ($m) | 2023-24 ($m) | 2024-25 ($m) | 2025-26 ($m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total levy recovered from PHIs | 11.8 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

3.3.2 Supervisory costs (restricted and unrestricted)

The tables below indicate the supervisory time incurred by APRA staff (actual, forecast and estimated) over a four-year period from 2022-23 to 2025-26 for the two elements of the non-PHI levy, being the supervisory (restricted) and systemic (unrestricted) elements of the levy. The time is reflected as percentages of the total time recorded.

Table 3: APRA’s supervisory effort by levy component

| Levy component | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 4-yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisory (restricted) | 58 | 56 | 63 | 59 | 59 |

| Systemic (unrestricted) | 42 | 44 | 37 | 41 | 41 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

The two components are then split, using the time-recording data, into the different industries.

Table 4.1: APRA’s supervisory effort by industry – restricted

| Restricted component | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 4-yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADIs | 45 | 46 | 47 | 46 | 46 |

| Life insurance/Friendly societies | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| General insurance | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Superannuation | 27 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 30 |

| PHI | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 4.2: APRA’s supervisory effort by industry – unrestricted

| Unrestricted component | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 4-yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADIs | 47 | 46 | 46 | 45 | 46 |

| Life insurance/Friendly societies | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| General insurance | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

| Superannuation | 25 | 28 | 30 | 33 | 29 |

| PHI | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

3.3.3 Direct costs

APRA’s costs can be split between:

- supervision-related or “front office” costs (frontline supervisors and specialist risk teams);

- systemic (policy setting and other industry-wide costs such as enforcement and data analytics, also referred to as “middle office” costs); and

- support functions (People & Culture, Information Technology, Finance, Property, etc. referred to as “back office” costs).

APRA’s time recording system captures time spent on each institution (and therefore industry) for front office costs. The middle office time spent on each industry is also recorded. The back-office functions primarily spend time on support and project-related activities.

The front office costs primarily relate to supervision, and therefore the amount of APRA’s overall effort supervising entities is known. For the purposes of the 2025-26 levies consultation paper (and as noted in table 3), 59 per cent of APRA’s effort is anticipated to be spent on supervision activities. This comprises the restricted element of the levy.

The remaining 41 per cent of effort is anticipated to be spent on systemic and industry-wide activities. This comprises the unrestricted element of the levy. Also included in this component of the levy are the non-APRA elements (ATO, Treasury and GNGB). Table 5 below is taken from the annual Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies for 2025-26 paper.12

Table 5: Total levies funding required

| Levies funding summary | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | Change | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRA | 246.1 | 243.0 | (3.1) | (1.3) |

| ATO | 45.6 | 37.2 | (8.4) | (18.4) |

| Gateway Network Governance Body | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 7.3 |

| Treasury superannuation consumer advocate | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 294.0 | 282.6 | (11.4) | (3.9) |

The total decrease of $11.4 million (or 3.9 per cent) in required levies for 2025‑26 is largely attributable to the $3.1 million decrease (or 1.3 per cent) in APRA’s levies requirement in 2025‑26, and a $8.4 million (18.4 per cent) decrease in the ATO component to support its activities of administering the Compassionate Release of Super program, and the Superannuation Lost Member Register (LMR) and Unclaimed Superannuation Money (USM) frameworks.

Taking account of the non-APRA levy elements above and applying the time-driven percentage splits to the element of the APRA cost base to be recovered by industry levies, the amount to be collected from each industry in the restricted and unrestricted categories can be determined.

3.3.4 Matching costs to income at an entity level (restricted component only)

One of the challenges of adopting a cost-recovery methodology is the avoidance of cross-subsidisation within each industry. This occurs where a disproportionately large or small levy is charged to a section of the industry, when compared to the actual cost of APRA supervision. Periodically APRA analyses detailed time-recording data on the actual cost of supervision available through its internal time recording system(s). This analysis has showed broadly consistent results each year, and as a result some modifications to the restricted levy component were made to the Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies from 2015-16 onwards.

Restricted levy minimums

One of the modifications noted above was a steady increase in the levy minimums for each industry from a historically relatively small amount.13 Prior APRA analysis indicated that the minimum restricted component of the levy for each sector continued to be generally too low. Gradual increases in minimums for each sector began in 2015-16 to address this issue. These increases were paused in 2019-20 and 2020-21, however, were reinitiated from 2021-22 onwards. For 2024-25 and 2025-26 there is a pause in the increase to the levy minimums, allowing the impact of these recent increases to embed itself more within each industry.

Restricted levy maximums

Consistent with the levy minimums review process, the levy maximums have been considered and modified each year, reflecting the observed cost of supervision. During 2018-19, various reviews impacted APRA-regulated industries14, resulting in APRA receiving a significant increase to its funding. In 2020-21 APRA funding was increased further to respond to the impacts of the pandemic through the measure “Treasury Portfolio – additional funding”. APRA’s funding for 2024-25 was increased through the measures “Cyber Security of Regulators and Improving Registers” and “Climate Related Financial Disclosures”.

For 2025-26 the levy parameters are:

- the restricted levy minimum for the ADI industry remains unchanged at $22,500, with the levy maximum increased from $7,500,000 to $8,500,000;

- the restricted levy minimum for the GI industry remains unchanged at $22,500, with the levy maximum unchanged at $1,600,000;

- the restricted levy minimum for the LI industry remains unchanged at $22,500, with the levy maximum unchanged at $1,200,000; and

- the restricted levy minimum for the superannuation industry (excluding pooled superannuation funds) remains unchanged at $12,50015, with the levy maximum increased from $900,000 to $950,000.

Other levy parameters are:

- Non-Operating Holding Companies (NOHCs) will have their levy unchanged at $45,000 per institution;

- the levy minimum for providers of Purchased Payment Facilities (PPFs) remains unchanged at $22,500 in line with other ADIs, with the levy maximum increased from $1,500,000 to $1,700,000;

- the levy minimum for foreign branch ADIs remains unchanged at $22,500, with the levy maximum increased from $1,500,000 to $1,700,000; and

- the levy minimum for pooled superannuation funds remains unchanged at $12,500, with the levy maximum increased from $450,000 to $475,000.

Authorised deposit-taking institutions

Table 6: Amounts levied on authorised deposit-taking institutions

| Asset base | $50m ($'000) | $500m ($'000) | $5b ($'000) | $25b ($'000) | $100b ($'000) | $800b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-25 | 22.9 | 26.4 | 149.1 | 745.6 | 2,982.7 | 13,712.0 |

| 2025-26 | 22.9 | 26.1 | 145.4 | 727.2 | 2,908.9 | 14,248.1 |

| Change (%) 2025-26 v 2024-25 | (0.0) | (1.1) | (2.5) | (2.5) | (2.5) | 3.9 |

Table 7.1: 2024-25 amounts levied on authorised deposit-taking institutions – breakdown

| 2024-25 asset base | $50m ($'000) | $500m ($'000) | $5b ($'000) | $25b ($'000) | $100b ($'000) | $800b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 22.5 | 22.5 | 110.3 | 551.5 | 2,206.2 | 7,500.0 |

| Unrestricted | 0.4 | 3.9 | 38.8 | 194.1 | 776.5 | 6,212.0 |

| Total | 22.9 | 26.4 | 149.1 | 745.6 | 2,982.7 | 13,712.0 |

Table 7.2: 2025-26 amounts levied on authorised deposit-taking institutions – breakdown

| 2025-26 asset base | $50m ($'000) | $500m ($'000) | $5b ($'000) | $25b ($'000) | $100b ($'000) | $800b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 22.5 | 22.5 | 109.5 | 547.6 | 2,190.4 | 8,500.0 |

| Unrestricted | 0.4 | 3.6 | 35.9 | 179.6 | 718.5 | 5,748.1 |

| Total | 22.9 | 26.1 | 145.4 | 727.2 | 2,908.9 | 14,248.1 |

The levy maximum for ADIs has been increased to $8.5 million and the levy minimum has been kept at $22,500. The restricted and unrestricted levy components have decreased across entities except for assets greater than $800 billion. Entities with greater than $100 billion assets contribute over 81 per cent of the industry levy of ADIs.

Life insurance

The year-on-year impact of the changes noted above are reflected in Table 8 below:

Table 8: Amounts levied on life insurers/friendly societies

| Asset base | $50m | $500m | $5b | $10b | $20b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-25 | 26.0 | 96.7 | 966.3 | 1,897.1 | 2,594.2 |

| 2025-26 | 25.4 | 85.4 | 853.7 | 1,707.4 | 2,355.3 |

| Change (%) 2025-26 v 2024-25 | (2.3) | (11.6) | (11.6) | (10.0) | (9.2) |

The changes across the asset sizes can be demonstrated by a further breakdown into the levy components in tables 9.1 and 9.2 below:

Table 9.1: 2024-25 amounts levied on life insurers/friendly societies – breakdown

| 2024-25 asset base | $50m | $500m | $5b | $10b | $20b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 22.5 | 61.8 | 617.7 | 1,200.0 | 1,200.0 |

| Unrestricted | 3.5 | 34.9 | 348.6 | 697.1 | 1,394.2 |

| Total | 26.0 | 96.7 | 966.3 | 1,897.1 | 2,594.2 |

Table 9.2: 2025-26 amounts levied on life insurers/friendly societies – breakdown

| 2025-26 asset base | $50m | $500m | $5b | $10b | $20b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 22.5 | 56.5 | 564.9 | 1,129.8 | 1,200.0 |

| Unrestricted | 2.9 | 28.9 | 288.8 | 577.6 | 1,155.3 |

| Total | 25.4 | 85.4 | 853.7 | 1,707.4 | 2,355.3 |

The levy maximum and levy minimum for LIs has been kept at $1.2 million and $22,500, respectively. Tables 9.1 and 9.2 show an overall decrease in the restricted and unrestricted levy components across different sized entities. Entities with greater than $10 billion assets contribute over 50 per cent of the industry levy of LIs.

General insurance

Table 10: Amounts levied on general insurers

| Asset base | $15m | $50m | $250m | $1b | $5b | $15b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-25 | 24.1 | 27.7 | 61.1 | 244.2 | 1,220.9 | 3,171.5 |

| 2025-26 | 23.7 | 26.5 | 49.9 | 199.5 | 997.7 | 2,805.1 |

| Change (%) 2025-26 v 2024-25 | (1.5) | (4.4) | (18.3) | (18.3) | (18.3) | (11.6) |

The changes across the asset sizes can be demonstrated by a further breakdown into the levy components in tables 11.1 and 11.2 below:

Table 11.1: 2024-25 amounts levied on general insurers – breakdown

| 2024-25 asset base | $15m ($'000) | $50m ($'000) | $250m ($'000) | $1b ($'000) | $5b ($'000) | $15b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 22.5 | 22.5 | 34.9 | 139.4 | 697.1 | 1,600.0 |

| Unrestricted | 1.6 | 5.2 | 26.2 | 104.8 | 523.8 | 1,571.5 |

| Total | 24.1 | 27.7 | 61.1 | 244.2 | 1,220.9 | 3,171.5 |

Table 11.2: 2025-26 amounts levied on general insurers – breakdown

| 2025-26 asset base | $15m ($'000) | $50m ($'000) | $250m ($'000) | $1b ($'000) | $5b ($'000) | $15b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Restricted | 22.5 | 22.5 | 29.8 | 119.2 | 596.0 | 1,600.0 |

Unrestricted | 1.2 | 4.0 | 20.1 | 80.3 | 401.7 | 1,205.1 |

Total | 23.7 | 26.5 | 49.9 | 199.5 | 997.7 | 2,805.1 |

The levy maximum and levy minimum for GIs has been kept at $1.6 million and $22,500, respectively. The restricted and unrestricted levy components decreased for all entity sizes. Entities with greater than $5 billion assets contribute over 48 per cent of the industry levy of GIs.

Superannuation

Table 12: Amounts levied on superannuation funds

| Asset base | $5m ($'000) | $50m ($'000) | $250m ($'000) | $1b ($'000) | $20b ($'000) | $50b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-25 | 12.7 | 14.1 | 27.6 | 110.3 | 1,554.4 | 2,535.9 |

| 2025-26 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 24.3 | 97.0 | 1,453.3 | 2,208.2 |

| Change (%) 2025-26 v 2024-25 | (0.3) | (2.7) | (12.1) | (12.1) | (6.5) | (12.9) |

Table 13.1: 2024-25 amounts levied on superannuation funds – breakdown

| 2024-25 asset base | $5m ($'000) | $50m ($'000) | $250m ($'000) | $1b ($'000) | $20b ($'000) | $50b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 12.5 | 12.5 | 19.4 | 77.6 | 900.0 | 900.0 |

| Unrestricted | 0.2 | 1.6 | 8.2 | 32.7 | 654.4 | 1,635.9 |

| Total | 12.7 | 14.1 | 27.6 | 110.3 | 1,554.4 | 2,535.9 |

Table 13.2: 2025-26 amounts levied on superannuation funds – breakdown

| 2025-26 asset base | $5m ($'000) | $50m ($'000) | $250m ($'000) | $1b ($'000) | $20b ($'000) | $50b ($'000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | 12.5 | 12.5 | 18.0 | 71.9 | 950.0 | 950.0 |

| Unrestricted | 0.1 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 25.2 | 503.3 | 1,258.2 |

| Total | 12.6 | 13.8 | 24.3 | 97.1 | 1,453.3 | 2,208.2 |

The levy maximum for superannuation entities has been increased to $0.95 million and the levy minimum has been kept at $12,500. The restricted and unrestricted levy components decreased for all entity sizes. Entities with greater than $50 billion assets contribute over 60 per cent of the industry levy of superannuation funds.

Private health insurance supervisory levy

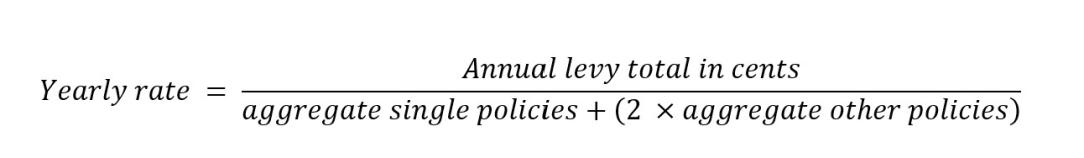

The PHI supervisory levy is a fixed price levy and is imposed directly upon insurers annually. It is calculated for each insurer, according to the number of single and other (e.g. joint) policyholders each insurer holds on the latest Census date. The basis of the calculation is the number of single policies plus twice the number of other polices each insurer has, multiplied by the year’s rate per policy for the industry. The year’s rate per policy is calculated as the annual levy in cents divided by the total number of single policies plus twice the number of other policies for the industry.

Every PHI entity is required to provide APRA with the number of single and other policyholders it has on the Census day. The reported data is audited annually.

No particular group or type of insurer draws regulatory focus disproportionately. All insurers are subject to the same regulatory framework. However, larger insurers tend to draw more of APRA’s analytical resources due to their complexity and importance to the private health insurance industry as a whole. Accordingly, a levy based on the number of policies held (a proxy for market share and consequently risk exposure to the industry) is appropriate as there is a direct correlation between the underlying cost drivers and market share.

The Private Health Insurance Supervisory Levy Imposition Act 2015 places an upper limit on annual levy rates of $2 per year for single person polices and $4 per year otherwise.

As noted in section 3.3.1 above, the calculation of the total to be collected from the PHI industry was in transition in 2019-20 from the Machinery of Government (MoG) costing to the APRA time-recording based allocation. From 2022-23, the PHI industry’s levy has been derived in the same manner as the other industries.

3.3.5 Matching costs to income at an entity level (unrestricted component)

For the unrestricted levy component, matching time recording data to an institution is not possible due to the nature of the work (e.g. industry-wide prudential standard/policy setting) as this applies to all institutions that operate within the industry concerned. Therefore, once the costs associated with any specific industry are allocated, the allocation to an institution is based on the methodology of allocation at that point in time. Currently, unrestricted levy costs are allocated to the ADI, superannuation, GI and LI industries on an assets basis.

The tables below demonstrate the costs recovered by the different levy components (restricted, unrestricted and PHI) and relate them back to the total APRA-approved budget for 2025-26.

Table 14: Cost and revenue estimates for 2025-2616

| Cost and revenue estimates | 2024-25 ($m) | 2025-26 ($m) | Change ($m) | Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APRA – operating expenses | 269.7 | 266.8 | (2.9) | (1.1) |

| APRA – contingency enforcement fund | 1.0 | 1.0 | - | - |

| Non-levy income | (21.1) | (21.7) | (0.6) | 2.8 |

| Prior year under / (over) collected revenue (recouped / refunded) from industry | (1.7) | (2.2) | (0.5) | 30.6 |

| Budget Measure – superannuation in retirement report framework | 1.3 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 55.0 |

| Removal of impact of AASB16 - Leases | (3.1) | (2.9) | 0.2 | (6.3) |

| Net funding met through industry levies | 246.1 | 243.0 | (3.1) | (1.3) |

Table 15: Breakdown of “Net funding met through industry levies” for 2025-26

| Activity component | Direct costs | Indirect costs | Depreciation / | Add. enf. resourcing, PY over-collection, add. funding | Net funding through industry levies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted levy | 98.8 | 27.1 | 10.4 | 0.5 | 136.8 |

| Unrestricted levy | 68.7 | 18.8 | 7.3 | 0.3 | 95.1 |

| PHI levies | 7.2 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 10.0 |

| NCPD special levy | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.2 |

| TOTAL | 175.6 | 48.1 | 18.6 | 0.8 | 243.0 |

The table below summarises APRA’s income budget for 2025-26 inclusive of levies, charges for service, and other income and relates this back to the APRA budget for 2025-26.

Table 16: Revenue estimates for budget year 2025-26

| Revenue estimates | Charge | Activity comp. | 2025-26 costs recovered ($m) | Recoup of 2024-25 over-recov. ($m) | Additional enforcement resourcing ($m) | Additional | APRA Revenue 2025/26 ($m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted levy | Levy | Restricted | 136.3 | (1.3) | 0.6 | 1.2 | 136.8 | ||

| Unrestricted levy | Levy | Unrestricted | 94.8 | (0.9) | 0.4 | 0.8 | 95.1 | ||

| PHI industry levies | Levy | n/a | 10.0 | - | - | - | 10.0 | ||

| NCPD special levy | Levy | n/a | 1.2 | - | - | - | 1.2 | ||

| Other appropriations | Direct Appr. | n/a - * | 15.3 | - | - | - | 15.3 | ||

| Other charges | Charge | n/a - ** | 6.3 | - | - | - | 6.3 | ||

| Total revenue | 263.9 | (2.2) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 264.7 | ||||

* Other appropriations relate to the annual appropriation for interest and, wage and price movement adjustments.

** Other charges relate to various other types of fees and costs recovered, including: (i) ongoing costs recovered from institutions accredited to use internal models for capital adequacy purposes (BASEL framework); and (ii) costs recovered from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), RBA, and ABS.

3.4 Licensing/authorisation charges

Current application charges relating to licencing of ADIs, representative offices of foreign banks in Australia (FBROs), GIs, LIs, PHIs and NOHCs were reviewed during 2016-17 and the charges updated in 2017-18 and 2018-19. These charges will next be reviewed as part of the Treasury portfolio charging review.

The review in 2016-17 entailed examining all existing resourcing and task activities to ascertain if it was still relevant to charge and whether the methodology was consistent with the CRGs.

The legislative instruments, explanatory statements and CRISs can be found at:

- https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018L00770 - NOHC application fees

- https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018L00755 - ADI, GI and LI application fees

- https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2018L00753 - FBRO application fees

- https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2019L00250 - PHIs and restricted ADI application fees

The CRISs can also be located on the APRA website – see section 2.2 (via the links to the levy determinations).

The charges are provided in the schedule of charges below:

Table 17: Schedule of charges

3.4.1 Registrable superannuation entity (RSE) charges

RSE charges are stipulated under Reg. 3A.06 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994. Any amendment to RSE charges needs to be progressed by regulations as per the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 instead of by legislative instrument, which is the mechanism for amending other industry charges set out in this CRIS.

3.5 Annual fee-for-service charge activities: covering 2025-26

Some functions undertaken by APRA (as indicated in section 1.2.3) are not recovered through a levy but instead through direct user charges for service arrangements. Actual costed time and overheads expended on these tasks is used as the basis for the charges.

The charges are derived from the costs incurred by APRA in providing the services concerned and as such do not constitute a tax. Subsection 51(1) of the APRA Act provides that APRA may, by legislative instrument, fix charges to be paid to it by persons in respect of:

- services and facilities which APRA provides to such persons; and

- applications or requests made to APRA under any law of the Commonwealth.

Subsection 51(2) of the APRA Act provides that a charge fixed under subsection 51(1) must be reasonably related to the costs and expenses incurred or to be incurred in relation to the matters to which the charge relates and must not be such as to amount to taxation.

Fee-for-service charge activities undertaken in 2024-25 by APRA were:

- accreditation and ongoing review of internal models (Basel Framework compliance); and

- provision of statistical information to other government organisations.

3.5.1 Accreditation and ongoing review of internal models

The accreditation and ongoing review of internal models, which allows ADIs with sophisticated risk management systems to adopt the “advanced” approach for determining capital adequacy, is charged based on the need to recover APRA’s costs of assessing applications for model approval and on-going monitoring of capital adequacy using the models-based approach. Those costs are based on the estimated APRA staff time involved as well as the associated direct and indirect overhead costs.

Background to the fee-for-service annual charge

In June 2004, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (the Committee) released Basel II, reforming the 1988 Basel Capital Accord (the 1988 Accord). APRA implemented Basel II in Australia for all ADIs on 1 January 2008, through new prudential standards under section 11AF of the Banking Act. This has been further extended by the introduction of Basel III, which became effective on 1 January 2023. Under these standards, ADIs are able to determine their capital adequacy requirements using one of two methods: a standardised (default) method or a models-based approach that more closely aligns with an ADI’s individual risk profile. ADIs seeking to use the models-based approach must have APRA’s approval to do so.

How the charges are calculated

The ADI charge is based on the need to recover APRA’s costs of carrying out the on-going monitoring of the capital adequacy of ADIs using the models-based approach and assessing applications for approval. Those costs are based on an estimation of APRA staff time involved with an addition of direct and indirect overhead costs. On this basis, APRA’s total cost recovery in respect of the models-based approach for 2024-25 is $3.2 million (2023-24: $2.8 million).

The costs incurred in monitoring the capital adequacy of ADIs using the standardised method are recovered through general financial sector levies.

In 2024-25, the focus has been on the ongoing supervision of the capital adequacy of ADIs approved to use, or that are seeking approval to use, the models-based approach and policy development relating to revisions to the advanced modelling approach to credit risk capital requirements for Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ), Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA), National Australia Bank Limited (NAB), Westpac Banking Corporation (WBC), Macquarie Bank Limited (MBL), ING Bank (Australia) Limited (ING) and Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited (BEN).

Each of the six ADIs accredited to use the models-based approach will be charged an amount that reflects the relevant effort taken by APRA in providing them with modelling supervision. BEN is in the process of accreditation and does not benefit at this point. It is therefore charged a lower amount than the six ADIs that were accredited to use the model for the full year.

Description of the charges

The charge imposed by the instrument is based on a three-tiered structure:

- $609,000 excluding GST for NAB, ANZ, CBA and WBC;

- $449,000 excluding GST for MBL; and

- $257,000 excluding GST for ING; and

- $65,000 excluding GST for BEN.

APRA informed the affected ADIs of the proposed charges.

Table 18: Basel framework related charges: For the period 2021-22 to 2024-25

| Basel framework | 2021-22 ($m) | 2022-23 ($m) | 2023-24 ($m) | 2024-25 ($m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee expenses | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Allocated overheads | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| Net cost | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

3.5.2 Provision of statistical information

The provision of statistical information concerning financial sector entities to the RBA and the ABS is recovered through a charge for service arrangement.

Background for the 2024-25 annual charge

Under the Financial Sector (Collection of Data) Act 2001 (the FSCODA), APRA collects financial and other statistical information from ADIs, GIs, LIs, PHIs and superannuation entities.

The statistical information that financial sector entities are required to lodge with APRA is prescribed by reporting standards that are made by APRA pursuant to the FSCODA. The reporting standards detail the information required and are accompanied by forms into which the information is to be inserted.

In 2000 and 2001, APRA implemented a computer system (Direct to APRA (D2A)17) designed and constructed to collect, store and report on the statistical information from financial sector entities. The D2A system enables financial sector entities to lodge statistical information with APRA electronically, and it includes software that can be used to analyse and compile reports from the statistical information collected.

Subsection 3(1) of the FSCODA provides that the purpose for which statistical information is collected under that Act is to assist APRA in the prudential regulation of financial sector entities and to assist the RBA in the formulation of monetary policy. Also, as is acknowledged by subsection 56(5A) of the APRA Act, some of the statistical information will be relevant to the ABS’s function under the Census and Statistics Act 1905 in maintaining and disseminating statistics relating to the financial industry and the wider economy.

The statistical information that APRA provided to the RBA and the ABS during the 2024-25 financial year is described in the schedules attached to the legislative instrument.

The statistical information is provided to the two agencies at their request, and they have agreed to pay the charges for it that are fixed by the instrument.

How the charges are calculated

The costs of maintaining and operating the D2A system (and the associated APIs that have been subsequently developed to enhance the data transfer mechanism) during 2024-25 is based on the forecast costs for the year. These costs represent the costs of staff time expended in performing ongoing maintenance (including enhancement) of the system and in operating the system (which includes collecting, managing, analysing and distributing the statistical information). The proportion of the above-mentioned costs have been allocated to the RBA and the ABS, based on their usage of the D2A system during 2024-25. Such allocations are made based on full cost recovery:

- The charges relating to the RBA- and ABS-specific requests were estimated based on the quantum of staffing resources consumed, informed by APRA’s time management system. Such resources are costed based on the average yearly staffing costs, including an appropriate overhead costs allocation.

- The cost of shared services was then worked out based on the number of forms processed for each organisation as a proportion of the total number of forms processed. As expected, these costs are predominantly borne by APRA due to the fact that most of the usage is dictated by APRA requirements. The proportion relating to the RBA and ABS was arrived at by extracting the cost per form by considering all costs relating to shared services for the year 2024/25. The operating cost of the D2A and associated systems was shared by the agencies (RBA/ABS/APRA) in the following respective proportions: 17%:10%:73%.

- The development costs of the D2A system to be recovered for 2024-25 is based on the quantum of staffing resources consumed in delivering the Economic and Financial Statistics (EFS) collection, informed by APRA’s time management system. This cost is amortised over a five-year period based on an agreed proportion of 56 per cent and 44 per cent for the RBA and the ABS respectively. Prior to the development of the system, it was agreed that these costs would be recovered from the agencies over a five-year period.

- The cost of maintenance and operation of the APIs during 2024/25 was calculated based on the quantum of staffing resources consumed. These resources were costed based on the time spent on the API related activities, the average yearly staffing costs of the resources involved and an indirect overhead cost allocation. These costs are borne by the RBA due to the fact that the APIs were implemented to meet the needs of the RBA.

On the above basis, it was determined that the total cost of the services provided to the RBA amounts to $536,101. This amount consists of $420,486 for the provision of statistical information, $18,189 for the development cost of the EFS collection system and $97,426 for the maintenance and support costs of the data sharing APIs used by the RBA.

The total costs of services to the ABS have been determined to be $257,783. This amount consists of $243,492 for the provision of statistical information and $14,291 for the development cost of the EFS collection system.

Each of the charges are GST exempt as per Division 81 of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999.

4. Risk Assessment

APRA sets its non-PHI supervisory levy rates annually, based on estimates of relevant assets of entities that constitute the industries, at the key levy dates. An estimate is also made of the entities that will be APRA-regulated at the levy date (30 June). From these estimates, the restricted and unrestricted levy rates are calculated (refer section 3 for more details).

Overall, the setting of the annual levy rates and the subsequent cash collection is moderately complex, however APRA does not consider the processes to be overly onerous. Risks arising from the rate-setting and collection processes include:

- a potential cash-flow risk if an under-collection of levies arises, to the extent that APRA does not collect sufficient levies to fund its operations. This risk is mitigated as APRA holds adequate cash reserves for its operations; and

- a reputation risk for APRA if the incorrect levy rates are set, as this will lead to over- and/or under-recoveries for individual regulated industries, and for industry sectors. Over- and under-recoveries can never be completely eliminated due to the use of estimates in the levy setting process, however large variances are to be avoided to prevent undue volatility in levies collected.

5. Stakeholder engagement

An annual industry levies consultation process is undertaken by Treasury with input from APRA. This involves the provision of a paper, prepared by Treasury in conjunction with APRA, titled “Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies for 2025‑26”, to enable industry to provide views on the proposed levies for the upcoming financial year.

The annual consultation paper includes details relating to:

- APRA’s activities;

- a summary of APRA’s supervisory levy requirements;

- a summary of total financial institutions’ levy funding requirements;

- a summary of sectoral levy arrangements;

- proposed levy parameters (maximums and minimums);

- a summary of the impact on individual industries that APRA regulates; and

- supervisory levy comparisons between the current and upcoming levy year.

Industry feedback from this year’s consultation paper included:

- a request for ongoing transparency; and

- requests to increase the restricted levy component.

Consideration of the feedback has been taken in setting the final levy rates.

6. Financial Estimates

The budget for APRA and the corresponding forward estimates is provided in the table below.

Table 19: Future financial estimates18

| Future financial estimates | Forecast 2024-25 ($m) | Budget 2025-26 ($m) | Forward Estimate 2026-27 ($m) | Forward Estimate 2027-28 ($m) | Forward Estimate 2028-29 ($m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 273.1 | 268.8 | 260.3 | 259.9 | 258.8 |

| Restricted levy | 133.5 | 136.8 | 137.6 | 139.9 | 138.7 |

| Unrestricted levy | 104.9 | 95.1 | 95.6 | 97.2 | 96.4 |

| PHI industry levy | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| NCPD special levy | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Other income | 22.7 | 21.7 | 16.2 | 11.6 | 12.6 |

| Total income | 272.3 | 264.7 | 260.5 | 259.9 | 258.8 |

| Surplus / (deficit) | (0.7) | (4.1) | 0.3 | - | - |

7. APRA’s Performance

7.1 Financial performance

The following tables show APRA’s financial performance from 2021-22 to 2023-24:

Table 20: Expenses performance against budget for APRA19

| Expenses | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | 225.8 | 233.1 | 239.1 |

| Actual | 214.6 | 229.2 | 237.0 |

| Variance | 11.2 | 3.8 | 2.1 |

APRA underspent its budget in each of the past three financial years. The main drivers for the underspend are provided below:

- In 2021-22, the underspend was primarily due to lower supplier costs for some activity deferred into 2022-23 due to the on-going pandemic and lower employee benefits driven by lower staff levels and a further increase in the Government 10-year bond yield used to value leave provisions.

- In 2022-23, the underspend was primarily due to lower supplier costs driven by contractor labour market challenges which resulted in the deferral of activities into the 2023-24 financial year and lower employee benefits driven by lower staff levels and an increase in the Government 10-year bond yield used to value leave provisions.

- In 2023-24, the underspend was primarily due to lower employee benefit driven by lower staff levels and movements in leave provisions reflecting an increase in the Government 10-year bond used to value leave provisions, and lower supplier costs driven by the on-going contractor labour market challenges which resulted in the deferral of activities into the 2024-25 financial year.

Table 21: Revenue performance against budget for APRA

| Revenue | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budget | 229.3 | 225.0 | 238.0 |

| Actual | 232.1 | 219.1 | 240.7 |

| Variance | 2.8 | (5.8) | 2.7 |

APRA’s revenue was slightly higher budget in FY21-22. The variance to budget was primarily driven by a higher asset growth rate in the superannuation industry compared to forward looking estimates. In FY22-23, the under-collection was mainly driven by entity mergers, licence revocations and a lower than projected June 2022 quarter assets growth rate within the superannuation industry. In FY23-24, the higher revenue was mainly driven by the over-collection in the superannuation industry.

7.2 Non-financial performance

Over the last few years there has been a broad desire to improve accountability and transparency across the whole of the Australian Government. Enhancements have focused on non-financial performance and have resulted in changes across government agencies in general and regulators specifically.

The key changes are:

- the enhanced Commonwealth Performance Framework – enhancements made within the Public Governance, Accountability and Performance Act 2013 (PGPA Act), associated PGPA Rule and supporting guidance including new guidance for “Regulator Performance” (RMG 128); and

- the establishment of the Financial Regulator Assessment Authority (FRAA) on 1 July 2021 which is tasked with assessing and reporting on the effectiveness and capability of APRA and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).20 The FRAA assessment of APRA commenced in mid-2022 and a report has been provided in July 2023.

7.2.1 The PGPA Act – non-financial performance-related requirements

The PGPA Act non-financial performance-related requirements are intended to provide meaningful information to the parliament and the public by seeking to have “line of sight” from the stated objectives and key performance information provided in the PBS and Corporate Plan to the assessment of APRA’s performance against these objectives and indicators in the Annual Performance Statement included in the Annual Report.

Corporate Plans

APRA’s 2024-2025 Corporate Plan was published on APRA’s website in August 2024.21 An updated plan for 2025-2026 is expected to be published by August 2025. The plan outlines APRA’s key priorities and activities in pursuing its purpose over the four-year horizon and includes key performance measures that APRA will use to monitor and assess performance against the plan.

Annual Reports with Annual Performance Statements

APRA’s 2023-24 Annual Report was published in October 2024.22

The Annual Report provides an assessment at the end of the reporting period of the extent to which APRA has succeeded in achieving its purpose. The Annual Report contains an Annual Performance Statement reporting against performance measures outlined in APRA’s PBS and Corporate Plan.

7.2.2 Accountability and Reporting

APRA is accountable for its activities and performance through a wide range of longstanding mechanisms, including the following:

- APRA’s Annual Report is tabled in Parliament each year and includes the Annual Performance Statement;

- APRA makes regular appearances at Senate Estimates and the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, as well as ad hoc appearances before other committees;

- APRA receives a Statement of Expectations from the Government which sets out the Government’s policy priorities for the financial system and regulatory reform program and its expectations about the role of APRA, its relationship with regulated entities, industry stakeholders, Government, Treasury, responsible Ministers and other government bodies and regulators and issues of transparency and accountability. APRA’s Statement of Expectations was last reviewed and published June 2023 Statement of expectations;

- APRA issues a Statement of Intent in response to the Government’s Statement of Expectations. APRA’s Statement of Intent was last reviewed and published in June 2023 Statement of intent.

- APRA is subject to effectiveness and capability reviews by the FRAA and annual financial audits by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), as well as occasional performance audits; and

- APRA complies with the Government’s best practice regulation process administered by the Office of Impact Analysis, which includes cost-benefit assessments of regulatory changes and Regulation Impact Statements.

Other accountability and oversight mechanisms are outlined on APRA’s website here: Accountability and reporting.

8. Key forward dates and events

Table 22: List of key dates and events for 2025-26:

| Event | Date |

|---|---|

| Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) for 2025-26 | Spring / Summer 2025-26 |

| Pre-budget submissions for 2026-27 | Summer 2026 |

| Treasury Portfolio Budget Statement for 2026-27 | Autumn 2026 |

| Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory levies for 2026-27 consultation | May 2026 |

| Release of APRA’s 2026-27 CRIS | June 2026 |

9. CRIS approval and change register

The table below shows approvals and changes relating to the CRIS.

Date of CRIS | CRIS change | Approver | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

June 2025 | Certification of the CRIS | APRA Chair | Not applicable |

June 2025 | Agreement to the CRIS | Assistant Treasurer | Not applicable |

Footnotes

1The recovery of costs through the financial institutions supervisory levies for the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), the Treasury, and the Gateway Network Governance Body Ltd (GNGB) are generally not considered in this document.

2The CRGs indicate that “Departments of State must conduct periodic reviews of all existing and potential charging activities within their portfolios at least every five years….”.

4 APRA’s budgeted average full-time equivalent staffing level has increased from 785 in 2020-2021 to 907 in 2025-26.

52020-21 was the final year performance bonuses were incurred, with a transitional payment allocated for 2021-22, and no performance bonuses from 2022-23 onwards.

6 Accounting Standard AASB16 – Leases was adopted in 2019-20 changing the treatment of APRA’s property leases, increasing the related depreciation and amortisation expenses.

7 Payments where there is no relationship between the payer of the charge and recipient of the activity are not subject to CRGs, paragraph 6.

8 As described in the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Supervisory Levies Determination 2025.

9 The FCS does not apply to life insurance companies or to private health insurers.

10 Described as the census date for the private health insurance industry.

11 Representing the costs to be collected from the PHI industry.

12 Table 1 in the Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies for 2025-26 paper, link to paper: Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies for 2025–26 | Treasury.gov.au

13 In 2014-15 the levy minimums were; ADIs: $490, LIs: $490, GIs; $4,900, Super: $590.

14 Notably the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry; the International Monetary Fund Financial Sector Assessment Program; and The Productivity Commission Inquiries into: ‘Superannuation: Assessing Efficiency and Competitiveness’ and ‘Competition in the Australian Financial System’; the Financial Regulator Assessment Authority assessment of the effectiveness and capability of APRA.

15 The Small APRA Funds (SAFs) and Single Member Approved Deposit Funds (SMADFs) flat rate of $590 was left unchanged.

16 As per the annual Proposed Financial Institutions Supervisory Levies for 2025-26 consultation paper.

17 The D2A system is currently used in parallel with the modernised statistical data collection platform called ‘APRA Connect’.

18 The restricted and unrestricted levy split for the forward estimate years is indicative only.

19 Actual results as per APRA Financial Statements. Budget as per PBS of each respective year.

20 Financial Regulator Assessment Authority Act 2021: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2021A00063

21 The Corporate Plan can be located at: APRA Corporate Plan 2024-25

22 The Annual Report can be located at: APRA 2023-24 Annual Report