APRA Insight - Issue 4 2016

Liquidity stress testing in superannuation – key observations

Introduction

In 2015, APRA undertook a review of the superannuation industry’s approach to conducting stress tests on liquidity. The review examined how superannuation trustees were performing liquidity stress tests, as well as how they were using the results.

In general, APRA’s review found a variety of practices adopted for liquidity stress testing, with differing degrees of sophistication across the trustees examined as part of the review. While some improvements in this area have been made across the industry since the introduction of APRA’s prudential standard on investment governance in 2013, there were still instances of trustees treating liquidity stress testing primarily as a compliance exercise, and failing to use the results to enhance their investment decision making.

Trustees that fail to incorporate the results of liquidity stress testing into their decision making are disregarding a potentially useful source of intelligence. As a result, this failure to utilise stress test results in decision-making may lead to some trustees not optimising the amount of liquidity they hold, given the characteristics of their fund(s).

Why focus on liquidity?

The purpose of stress testing is to enhance an institution’s understanding of how an entity or portfolio performs under a range of scenarios, providing greater insight into the risks to which the institution is exposed and the possible impact of severe but plausible adverse events.

When, as is common, the primary focus of stress tests is on investment returns1, it may lead to liquidity issues being overlooked. Stresses that affect liquidity may not necessarily impact returns (or asset values) immediately; in some circumstances, liquidity may be the most potentially severe risk faced by a superannuation fund in the short run – as occurred for some funds in the global financial crisis. Poor investment performance may ultimately lead to a failure to meet investment return objectives, and can lead to reduced confidence in the fund, but may not lead to a permanent loss of capital. If it has inadequate liquidity, however, a superannuation fund could be forced to sell assets during a market downturn, thus crystallising losses. Furthermore, these losses could be more severe due to the adverse market impacts that are likely to be occurring at the same time.

Liquidity stress tests help trustees understand the possible impact of deteriorating conditions on a superannuation fund’s investment portfolio, and the possible severity of such impacts. An enhanced understanding of a fund’s liquidity profile, and the likely impacts of an adverse liquidity environment, better enables a fund to determine the extent to which they are able to invest in illiquid assets on an ongoing basis, and hence to better optimise their decisions about required liquidity.2

APRA’s requirements and other considerations

APRA’s Superannuation Prudential Standard SPS530 Investment Governance establishes broad requirements for trustees to develop an investment strategy, effectively implement that strategy, monitor and assess the performance of the strategy and its implementation, and manage the risks of the investment strategy and its execution. There are requirements in the standard that relate to liquidity management, and the conduct of stress tests on investment portfolios.

Beyond these regulatory requirements, there are a range of broader factors that compel trustees to focus on liquidity management, such as demographic and net cash flow trends. The Australian superannuation system is maturing, with an increasing proportion of fund members entering the retirement phase. This, in turn, increases the need for liquidity to meet benefit payments (whether lump sum payments or retirement income streams). Indeed, an increasing number of superannuation funds are in a situation of net cash outflow – that is, paying out more in benefits than they receive in contributions. Trustees’ investment strategies need to have regard to the implications of these trends for the liquidity profile that is needed, and in particular the potential reduction in the range of investments that may be necessary in order to ensure adequate levels of liquidity are maintained.

In short, these trends require trustees to undertake periodic review and analysis, including cash flow projections, of their desired liquidity profile; this need is particularly acute where funds are not able to rely on cash inflows to meet liquidity needs.

Key observations from APRA’s review

The review of liquidity stress testing indicated a variety of practices across trustees; while some trustees devoted considerable effort and resources to their stress testing activities, quite a number failed to use the results in their investment decision making in any meaningful way.

The key determinant of the quality or effectiveness of liquidity stress testing was management attitude and operational culture. Those trustees that evidenced better practices in undertaking and using the results of liquidity stress testing demonstrated the following characteristics:

- performing liquidity stress tests (or at least part thereof) themselves, rather than outsourcing it to external suppliers;

- seeking and using data3 that was more specific and relevant to their circumstances to enhance the insights provided; and

- applying the results of the stress tests in their investment decision making.

Conversely, those trustees that were not as mature in their application of liquidity stress testing:

- treated it as primarily a compliance exercise;

- placed almost complete reliance on asset consultants to perform the stress tests; and

- did not incorporate the results of the stress tests into their investment decision making (for example, the results were provided/considered with inadequate evaluation of, or commentary on, their implications).

Interestingly, many of the trustees that had sought and obtained more detailed data to undertake their liquidity stress testing also often indicated a desire to obtain even more detailed, specific and relevant data to further enhance their approach in this area. This was consistent with APRA’s observation that the board and management’s attitude to undertaking and using stress tests was critical, and had more impact on the quality of stress testing and its application than factors such as fund size, asset allocation, membership profile or the allocation to illiquid assets.

Undertaking stress tests internally (even if only partially) also had a significant impact on their value. Where this was the case, the trustee appeared better able to apply their knowledge of their own circumstances, such as more detailed information on their investment portfolio and fund membership, in the testing that was conducted. On the other hand, trustees that entirely outsourced their liquidity stress tests to consultants typically relied on more standardised assumptions or stresses, which did not adequately reflect the particular nuances of their operations.

Conclusion

While some improvements have been made in liquidity stress testing across the superannuation industry since the introduction of APRA’s prudential standard on investment governance in 2013, further enhancements are needed. Liquidity stress testing should not be viewed as primarily a compliance exercise; rather such testing should be tailored to reflect the particular features and circumstances of the trustee’s operations and used to enhance investment decision making. This is critical in light of broader factors impacting the superannuation industry, including demographic and net cash flow trends, which will increasingly require trustees to devote even greater attention to sound liquidity management.

1 The impact of stress scenarios on investment returns will typically be considered as part of investment or portfolio stress testing.

2 A key requirement of being an effective long-term investor is the ability to determine the time of sale of assets. Being a forced seller of assets (or even facing that prospect) impedes the ability of a fund to operate as a true long-term investor.

3 More advanced funds obtained a range of relevant asset and member data in the context of their own fund. This includes consideration of their specific asset holdings (rather than just asset class level data), member data including demographic details as well as sources of membership (eg default, direct, advisor), as well as their own historical experience across these aspects. Sources used could include their own records, their custodian, investment managers and administrators as well as market relevant data.

Life insurance industry stress test results

In 2015, APRA undertook its first comprehensive stress test of the life insurance industry, as part of an expanded stress testing program that APRA has established across the banking and insurance industries. The results of the stress test were provided to participating insurers and APRA’s key insights were released publicly in August 20161. This article provides information on the results of the stress test, as well as some of the lessons for industry.

The scenario

The scenario chosen for the stress test was similar to that developed for the banking sector in 2014 but with specific focus on disability income insurance, a product that has in recent years become problematic for the life insurance industry.

The scenario had a three-year time horizon. At a macro level, the scenario involved a downturn in the Chinese economy leading to a decline in global growth and a recession in the Australian economy: GDP fell by five per cent and unemployment increased to 14 per cent. The stress also impacted asset classes, with severe downturns in property and equity prices and government bond yields, and an increase in credit spreads. As such, the stress was two-pronged, targeting both sides of the balance sheet.

Importantly, the scenario was considered by APRA to be both plausible and sufficiently severe: in all cases, life insurers needed to undertake significant mitigating actions to protect their businesses.

Results

The capital impact of the stress test differed markedly across the participants. This was expected given the heterogeneous nature of the mix of diversified insurers, reinsurers and risk specialists involved in the exercise2 . In terms of their own stress testing capabilities, participating life insurers were also at different stages of evolution and preparedness. This meant that in analysing the results, APRA focussed not only on the relative capital impacts, but also on the range and feasibility of the mitigating actions proposed, and other qualitative comparisons in relation to governance and modelling capabilities.

The stress test was not constructed as a pass-fail exercise3. Rather, APRA’s intent was to identify potential vulnerabilities within the industry and inform participants how better to make their capital decisions, set target surplus thresholds and achieve greater understanding of the dynamic between their capital and business risks.

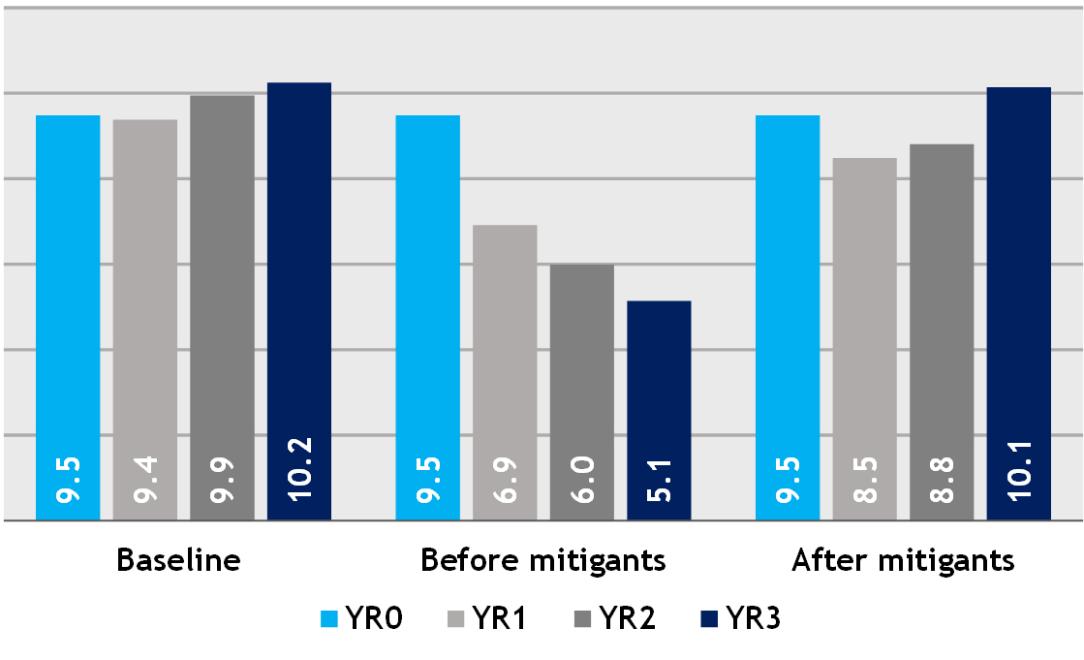

Figure 1 quantifies the direct impact of the scenario on the aggregate capital base of the insurers involved in the stress test against their baseline position4, both before and after taking account of the mitigating actions insurers indicated they would deploy to avoid or limit the impact of the adverse conditions. The figure shows a potential capital reduction - before mitigating actions - of $4.4 billion (a 46 per cent decline) from the baseline position (Year 0) to the end of Year 3. After allowing for mitigating actions, insurers managed to maintain capital at near pre-stress levels by the end of Year 3.

Figure 1 - Aggregate capital base ($bn)

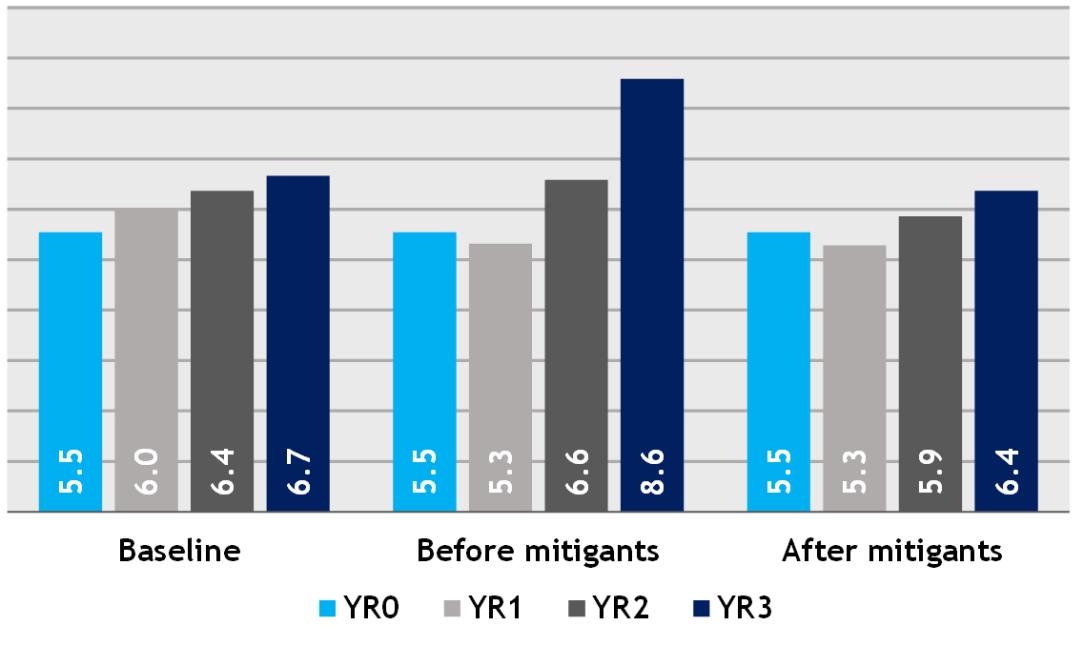

Figure 2 - Aggregate PCA impact ($bn)

The impact on the regulatory capital required under the scenario (i.e. the Prescribed Capital Amount or PCA) both before and after mitigating actions were applied is shown in Figure 2. Before taking into account mitigating actions, the aggregate PCA across participating insurers would have increased by $3.1 billion (55 per cent) over the three year scenario. Once again, after mitigating actions, insurers managed to reduce the aggregate PCA to near pre-stress levels.

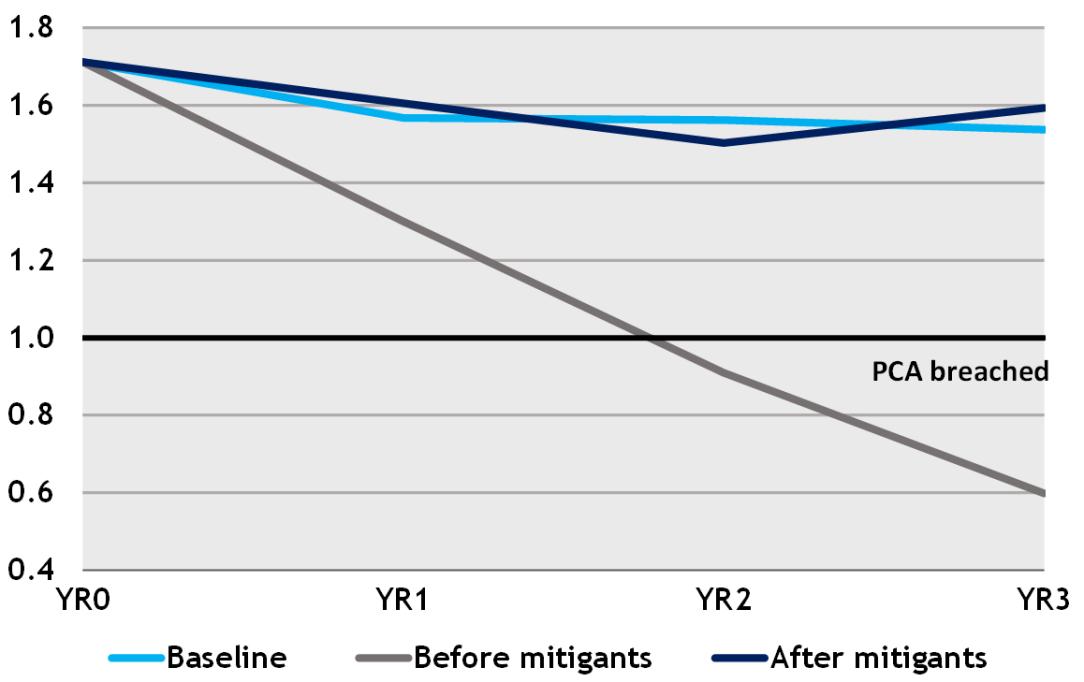

The aggregate capital base and PCA movements impacted regulatory capital coverage ratios, shown in Figure 3. Before allowing for mitigating actions, the insurers in aggregate would have breached the minimum PCA just before the end of Year 2. After mitigating actions, however, aggregate PCA coverage held at a level similar to the baseline projections by the end of Year 3.

Figure 3 - Aggregate PCA coverage ratio

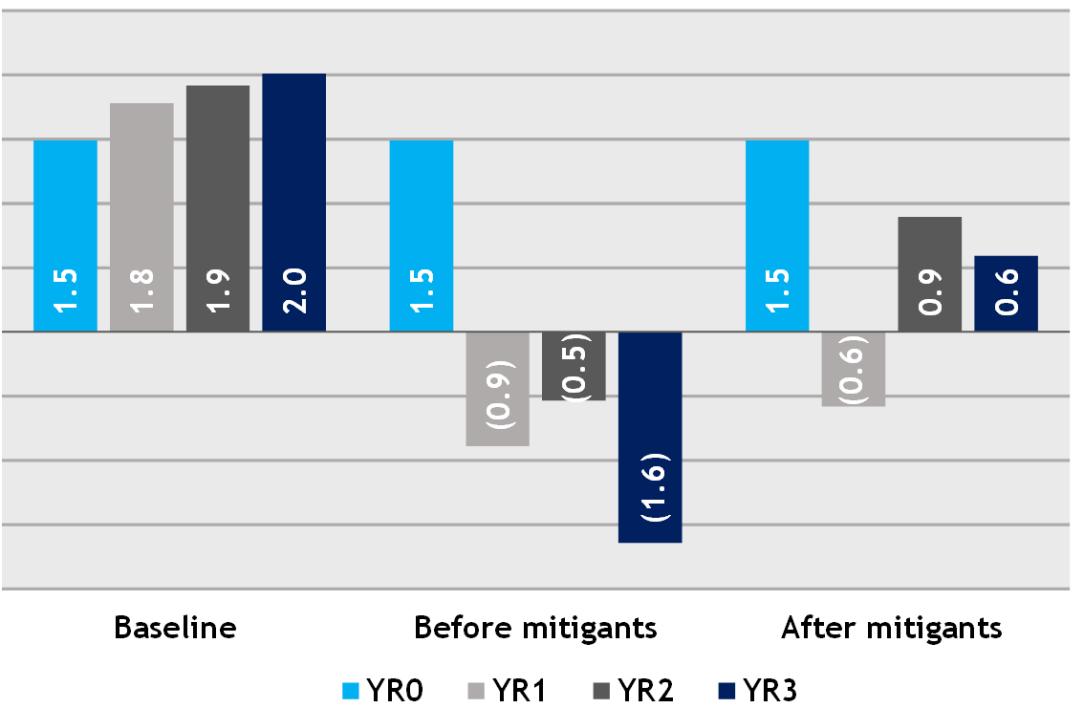

Figure 4 - Aggregate profit impact ($bn)

Figure 4 shows the impact of the scenario on aggregate profitability. Without allowing for mitigating actions, those involved in the stress test would have recorded a combined loss of around $900 million in Year 1, growing to $1.6 billion by the end of Year 3. Profitability improved once insurers factored in various mitigation strategies, including repricing. However, unsurprisingly given the extent of the stress, this was insufficient to enable the industry to return to anything like its baseline profitability.

Key insights

The impact of the stress scenario on the capital base of participating insurers differed considerably, depending on their business models. As expected, those with a greater exposure to disability income insurance were impacted more by the liability stress; other insurers with relatively higher risk asset portfolios found the asset stress was the key driver of outcomes. While the stress test did not expose any new risks that were unknown to APRA or the industry, a few key themes were identified.

Mitigating actions

In responding to the stress scenario, a range of management actions were applied to help preserve and restore insurers’ capital. The most common of these were premium rate increases, the reduction or suspension of dividends, and capital injections. Those insurers with more diversified business models were typically able to employ a wider range of mitigating actions than insurers with a more limited product offering.

While most insurers provided justifications for the validity and feasibility of the mitigating actions chosen, some actions posed challenges in terms of reliability, timing and ease of implementation. Pricing increases is one such example, as time is required for their expected benefits to be realised. There are also significant assumptions required as to how competitors might react, as well as how customer behaviour is impacted and the extent to which premium growth or lapse rates are affected. Similarly, shareholder and market reaction to capital injections or dividend reductions, particularly over a prolonged period, are difficult to predict.

A key lesson for Boards and senior management from the stress test is to ensure they understand any assumptions and constraints associated with the proposed management actions, and to be aware that under real-time duress, the assumptions applied in this scenario may differ from reality.

Governance and process

Insurers participating in the exercise were required to submit qualitative information to APRA, demonstrating the deliberations by the business, including Boards and senior management, of the stress scenario and documenting key assumptions and management insights. These submissions varied from comprehensive to less so.

One of the messages to industry is for Boards to be proactive in their engagement with stress testing exercises. Stress testing should not be seen primarily as a quantitative exercise in modelling, but rather as a tool by which the robustness of an insurer’s balance sheet, its capacity to handle severe adversity, and the adequacy of its existing capital can be tested. Critically, it is the availability of actions to reduce the impact of the stress that are often the most informative part of a stress testing exercise. It also helps draw out any strategic implications for the business.

Some life insurers adopted more robust stress testing processes and models than others. Adopting a whole-of-business approach was considered better practice. This means involving and seeking input from all parts of the business in workshop environments as the scenario played out.

Recovery planning

As with all stress tests, scenarios are hypothetical, conducted under laboratory-type conditions and an artificial time frame. For reasons of expediency, this necessarily involves assuming away or simplifying some aspects of how a scenario might play out in practice. Most significantly:

- As indicated, parameters are prescribed in advance and there is time to respond and consider options in an orderly fashion. In reality, when a stress occurs the impact may be more immediate and challenge even the most well-prepared insurers. Most importantly, the future evolution of the scenario at any point of time cannot be known, meaning decisions on how to respond to a real life stress need to be made in an environment of much greater uncertainty.

- The complexities and uncertainties of markets, customers, competitors and other environmental factors would inevitably be different than those prescribed in any given stress testing exercise. And equally importantly, the mitigating actions proposed may not necessarily have the impact expected for recovery in real time.

Such uncertainty emphasises the importance of robust recovery planning. Recovery planning and stress testing are inherently linked – having in place well considered plans for responding under duress should to be a priority for life insurers, as it is for all APRA-regulated industries.

Future stress testing

Life insurers have been developing their own stress testing practices in recent years. What was once viewed as a backroom activity performed by actuaries is increasingly becoming an enterprise-wide exercise, involving the Board and senior management, providing key insights to shape an insurer’s business strategy.

The insurance industry can expect a continued focus on stress testing by APRA, with the next comprehensive life insurance stress test scheduled for 2018. Life insurers, whether or not they participated in this stress test, should continue to improve their own stress testing capabilities as a matter of good practice. Regularly asking the question: ‘what if?’ will inevitably help preparedness for unexpected adversity and improve resilience in the long run.

1 https://www.apra.gov.au//media-centre/media-releases/apra-announces-results-stress-test-life-insurance-industry

2 The participants represented some 54 per cent of the market as measured by net premium revenue or 73 per cent as measured by gross policy liabilities (as at 31 December 2015).

3 For this reason, unlike practices which have evolved in other jurisdictions, APRA does not publish individual entity results of stress tests.

4 Baseline represents current projected business plans before any consideration of the stress scenario.

Private health insurance prudential policy roadmap

On 1 July 2015, APRA assumed responsibility for the prudential supervision of the private health insurance (PHI) industry from the former Private Health Insurance Administration Council (PHIAC). To facilitate the transition of responsibilities, APRA undertook to not make any substantive changes to the private health insurance prudential framework during its first year of oversight, with APRA’s priority being to build a detailed understanding of PHIs and communicate its supervisory approach to the industry.

Now in its second year of responsibility, APRA held a series of meetings with insurers throughout 2016 to discuss its roadmap to review the existing PHI prudential framework. The goal of the review is to ensure that the prudential framework remains fit for purpose. The review is expected to proceed at a measured pace, with a three-stage program reviewing selected standards over the next three years. The initial phase of this program of work will focus on risk management standards, and be followed by subsequent phases examining governance and capital standards.

Phase 1: Risk Management

Consultation on the development of a risk management prudential standard1 commenced in December 2016 with the release of a discussion paper setting out APRA’s proposed risk management requirements for the private health insurance industry.

The paper draws heavily on research undertaken by PHIAC between 2007 and 2014 in assessing the risk management practices of the industry; but also includes observations from risk management thematic reviews currently being undertaken by APRA. It also reflects APRA’s experiences in developing and implementing the existing cross-industry prudential standard on risk management (CPS 220 Risk Management). Responses to the discussion paper will help inform APRA’s view as to whether it is appropriate for CPS 220 Risk Management to be applied to the private health insurance industry.

During 2017, APRA also intends to consult the industry on prudential standards for outsourcing and business continuity management. As part of that consultation, APRA will consider whether it is appropriate to apply all or part of its existing prudential expectations for other industries to private health insurers.

Separately to this work, APRA is currently undertaking a holistic review of its expectations of the role of the appointed actuary and actuarial advice2 in the life and general insurance industries to ensure the existing prudential standards (GPS 320 Actuarial and Related Matters and LPS 320 Actuarial and Related Matters) remain fit for purpose. As many of the principles to be considered in this review are also likely to be relevant to the private health insurance industry, PHIs and their actuaries are being encouraged to contribute to this review.

Phase 2: Governance

When APRA’s consultations on risk management are further progressed, APRA intends to undertake a comprehensive review of HPS 510 Governance. As part of this review, APRA will consider whether the existing cross-industry prudential standard (CPS 510 Governance) should apply to the private health insurance industry. This will include consideration of issues such as the independence of directors, tenure, assessment and appointment processes, as well as board engagement with APRA. Any changes to the existing standard for PHIs - HPS 510 Governance - will, of course, be subject to APRA’s normal consultation process.

APRA also plans to review the prudential functions of private health insurance auditors. Separate audit standards exist for all other industries regulated by APRA and provide for independent assurance of prudential matters by an appropriately qualified auditor. This contrasts with the private health insurance industry where prudential standard requirements are currently more limited.

APRA also intends to consult on establishing a fit and proper prudential standard for directors, senior managers, auditors and appointed actuaries of PHIs during 2017/18. APRA’s starting point is that this would be aligned with the provisions of APRA’s cross-industry prudential standard CPS 520 Fit and Proper, with the objective of ensuring that insurers undertake sufficient inquiry to determine that key persons have the appropriate skills, experience and knowledge, and act with honesty and integrity in performing their roles.

Phase 3: Capital

APRA does not propose to review prudential standards HPS 100 Solvency or HPS 110 Capital Adequacy in the short term, unless a prudential issue or other change arises which warrants an earlier review. APRA envisages a review of these standards in 2018/19, by which time both the industry and APRA will have had a more substantial period of experience with the current requirements.

1 https://www.apra.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/apra-releases-consultation-package-risk-management-private-health

2 Consultation on the role of the Appointed Actuary - June 2016

On 9 November 2016, APRA released the 2015/16 Operations of Private Health Insurers Annual Report. This is the second edition of the report to be released by APRA, and details the operations of private health insurers including:

- premiums and other amounts payable to the fund;

- fund benefits and other amounts payable out of the fund;

- management expenses;

- the balance of the fund as at the end of that year; and

- how the assets of the fund have been invested.