The System Risk Outlook provides an overview of risks and vulnerabilities affecting the Australian financial system, from the perspective of Australia’s financial safety regulator.

Why has APRA launched this report?

As Australia’s financial safety regulator, APRA plays an important role in managing risks and preventing the build-up of vulnerabilities in the financial system. Our system-wide view of the operating environment helps us understand the different ways that shocks could flow through the system, assess how interconnections across sectors could amplify those shocks, and identify emerging risks early. Across the entities we regulate, APRA continues to ensure existing and emerging risks are managed appropriately against prudential requirements to support financial stability, while also allowing the financial system to operate in a competitive and efficient way.

The System Risk Outlook report has been launched to increase transparency around what APRA is seeing in the risk environment. This report complements publications from other agencies on the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) who are responsible for different aspects of the stability of the Australian financial system. APRA and peer CFR agencies – the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), and the Treasury – monitor a range of risks and vulnerabilities in regulated industries and in the Australian financial system. APRA’s new twice-yearly report will highlight some of the risks and vulnerabilities that are key focus areas for APRA. It is not exhaustive of all risks and vulnerabilities that APRA monitors. In forming our assessments, we draw on our engagements with regulated entities, staff analysis, and information shared between peer regulators. Importantly, the discussion in this report is centred on the risk environment facing APRA-regulated entities, rather than current or potential future supervisory activities by APRA.

Summary

The Australian financial system, including APRA-regulated entities across banking, insurance and superannuation, continues to be safe, stable and resilient. The system is well-placed to absorb potential adverse shocks in a rapidly changing, complex and highly interconnected operating environment. Similarly, the entities that APRA regulates are judged to be resilient if adverse shocks were to materialise, meaning they could continue providing critical financial services to the community.

To ensure this resilience is maintained, APRA is carefully monitoring developments in the international and domestic environments. Three areas are of particular focus.

Geopolitical environment

More than two-thirds of APRA’s regulated entities think geopolitical risk is a top concern.

- Globally, regulators and industry are stepping up their focus on geopolitical risks.

- Geopolitical risks are challenging to manage because they can transmit through the financial system via many channels and trigger multiple disruptive risk events at the same time. Some of those transmission channels and risks are well understood, but others are newer and unique to geopolitical events.

- In this context, APRA and the CFR agencies are strengthening the system’s resilience through a dedicated geopolitical risk work program. This is a forward-looking initiative designed to ensure industry is more aware of the wide-ranging impacts of geopolitical shocks on the financial system, and that institutions can respond to unexpected disruptions.

Housing

For almost a decade, gross debt of Australian households has been around 1.8 times their incomes, making this a key vulnerability in the financial system.

- Household debt in Australia has been high by both historical and international standards for some time.

- As interest rates have declined this year, APRA has observed housing price growth strengthen and an increase in investor activity. Housing lending standards have remained sound but there are signs of a pick-up in some forms of higher risk lending and heightened competition for new lending.

- Given these dynamics, aggregate household indebtedness could increase further, and other housing-related vulnerabilities could build. APRA is carefully monitoring these dynamics and has been engaging with the lenders it regulates to ensure a range of macroprudential policy tools can be implemented where needed.

Interconnectedness, particularly the growing role of superannuation

The superannuation industry has doubled over the past decade, and its response in a crisis can impact the whole financial system, including banks.

- There are significant interconnections in the Australian financial system, both financial and non-financial. These interconnections help the system operate more efficiently but also introduce new vulnerabilities.

- The superannuation industry plays a unique role in Australia’s financial system. Historically, it has played an important role as a stabiliser when shocks occur. But with its growing size and linkages across the system, particularly with banks, the industry’s response in a crisis could also amplify stress in some scenarios.

- APRA is looking closely at how these interconnections might affect the stability of the financial system if there was a severe, unexpected shock. APRA’s exploratory stress testing suggests that super funds can continue to be a stabilising force during a shock, but in some cases, their actions can also amplify the negative effect of the shock on members and the system.

What do we mean by financial system vulnerabilities?

APRA is Australia’s financial safety regulator. This means it is responsible for ensuring that the entities it regulates – including banks, insurers, and superannuation funds – can meet their obligations to customers. These entities form part of the wider Australian financial system.

The financial system is a key enabler of economic activity. It does this by allowing money to flow smoothly around the economy. One of the key roles of regulators like APRA is to ensure the financial system can continue to function even when something unexpected happens, such as a shock from overseas.

When we look across the system for things that might cause instability, we focus on identifying material vulnerabilities. Vulnerabilities are weaknesses or imbalances in the system that can amplify shocks. They might not be cause for concern on their own but, in the context of the system, they could make the impact of shocks much worse.

One way to think of a vulnerability is like a crack in the roof of a house. It might not always be obvious or a cause for immediate concern, but if a storm came along, the crack would make the house more likely to leak and damage what’s inside. The water damage could also affect the wider neighbourhood if other homes had similar issues, or if the water damage affected the foundations of nearby buildings or utilities.

This focus on vulnerabilities, including how multiple vulnerabilities can interact, helps APRA take pre-emptive action and promote stronger resilience to prevent harm before it occurs. Just like engineers inspect buildings for structural integrity before a storm, when APRA spots a vulnerability, we work with our peer regulators to assess it and potentially take mitigating actions. These actions help to build resilience so that the system can absorb – rather than amplify – shocks when they inevitably occur. The Financial Stability Board and the RBA have a similar focus on vulnerabilities and resilience.

APRA has a range of tools to support financial system resilience, and we work closely with other agencies on the CFR to do this. One example is macroprudential policy, discussed in Box B. Importantly, APRA does not pursue resilience at all costs. Instead, we seek to allow the financial system to operate in a competitive and efficient way, while providing the Australian people with an appropriate level of protection so that the system can withstand future storms.

The international environment

APRA is seeing: A heightened and complex international risk environment, and regulators in Australia are working together to prepare the financial system for a range of potential scenarios.

Risk environment

While Australia is geographically isolated, its financial system has deep interconnections with those of other countries. These interconnections, which can include products, markets, technologies and communications, mean that shocks from abroad can affect the Australian financial system via many channels. So, to protect the financial interests of Australians, it is vital that APRA pays close attention to developments in the international risk environment and potential spillovers for Australia.

APRA is seeing that risks from overseas are currently heightened and are expected to remain so for the foreseeable future. New and interacting risks have also made the international environment more complex to monitor and prepare for.

Global economy

There are downside risks to global economic growth from weaker trade, heightened policy uncertainty, bouts of financial market volatility and heightened geopolitical tensions. A volatile geopolitical environment, including ongoing conflicts, sustained strategic power rivalries and the straining of longstanding economic, trade and security alliances, is likely to fundamentally characterise global affairs for some time.

Legal & regulatory

Scrutiny on the costs of financial sector regulation globally has increased against a backdrop of productivity concerns. Some regulators have announced plans to pare back requirements to reduce burden. Generally, they are maintaining minimum international standards but focusing on simplification and removing aspects that are stricter than the baseline rules. There are also emerging signs of regulatory fragmentation.

Technological

Geopolitical unrest has been correlated with an increase in cyber-attacks. An ever-greater reliance by financial institutions and their customers on digital technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), is also creating more opportunity for cyber adversaries. The concentration in third-party service providers throughout the technology supply chain can amplify any shocks leading to a wider impact.

Social

Many advanced economies are experiencing ageing populations and diverging financial priorities between younger and older generations. Growing community mistrust in governments and institutions is also affecting social cohesion in some countries.

Environmental

Similar to Australia, other countries are experiencing changes in the frequency and severity of major weather events. International policy positions on climate change continue to evolve and could have flow-on impacts for the Australian financial system.

Vulnerabilities

APRA is focused on strengthening crisis readiness so that the Australian financial system can absorb – not amplify – shocks from the global environment. We are particularly focused on ensuring the Australian financial system is prepared for geopolitical shocks and operational disruptions and we are working closely with other regulators and industry to strengthen resilience. We are also alert to developments in global financial markets and potential spillovers to Australia.

APRA is working with peer regulators to ensure the Australian financial system is prepared for a range of geopolitical scenarios.

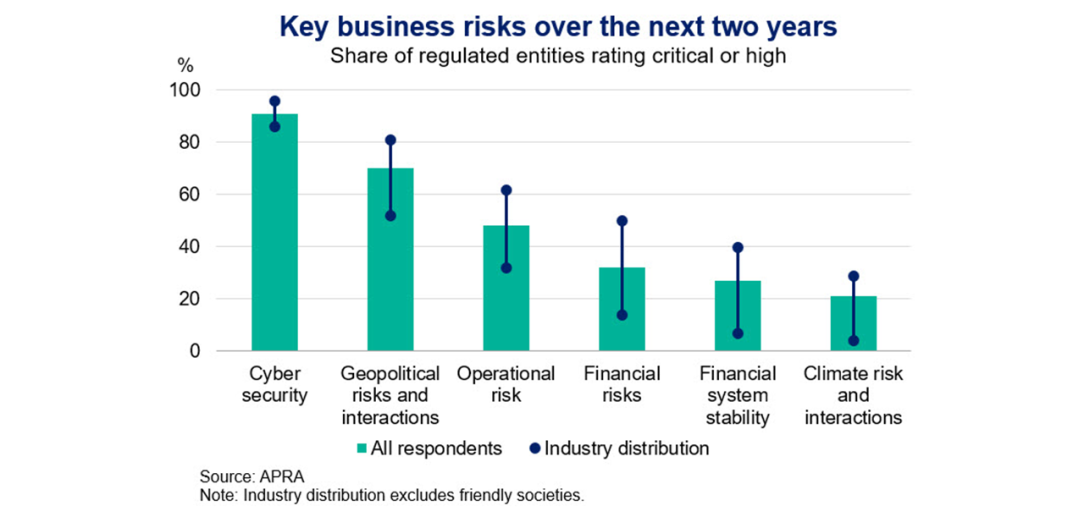

APRA and the CFR agencies have identified a lack of preparedness for geopolitical shocks as a key vulnerability in the Australian financial system. This view is shared by the entities APRA regulates, with 70 per cent nominating geopolitical risk, and its potential to magnify other types of risk, as being of critical or high concern in APRA’s recent stakeholder survey (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Geopolitical risk is particularly difficult to manage because shocks can transmit rapidly through the financial system via a wide range of channels. This includes financial and economic channels, which are generally well understood by industry and regulators, as well as other channels such as safety and security (Box A). As a result, geopolitical shocks can trigger multifaceted risk events that encompass financial impacts, operational impacts that ultimately have financial consequences, and even personnel or political impacts such as foreign interference or sanctions enforcement.

While financial institutions are attuned to the volatile geopolitical climate, APRA is seeing that the level of maturity of geopolitical risk management varies greatly. Through our recent engagements, APRA has observed that institutions with higher risk maturity are leveraging structured, cross-functional expertise to proactively scan the external environment and generate actionable insights. However, there remains a significant opportunity across all entities to strengthen risk management practices. This includes:

- embedding geopolitical considerations holistically into enterprise risk frameworks, ensuring they are not treated as isolated factors; and

- expanding factors beyond financial impacts to encompass non-financial risk dimensions, such as operational resilience, regulatory shifts, and reputational exposure.

By integrating these elements, institutions can move from reactive responses to having more strategic foresight, which will enhance their ability to navigate the complex geopolitical landscape.

Together with our CFR peers, APRA has committed to a dedicated geopolitical risk work program focused on strengthening the preparedness of the financial system to a range of geopolitical scenarios. This multi-year initiative is sharpening focus on horizon scanning to anticipate, withstand, and respond to disruption. Important attributes of this work include bolstering payments system resilience, increasing focus on personnel risk and sanctions preparedness, and enhancing crisis coordination and response protocols. This work program adds to several related initiatives already underway to reinforce financial system resilience, including a new prudential standard for operational risk (discussed below). Ensuring entities consider the wide range of transmission channels for geopolitical shocks is something we are raising in our routine supervisory engagements.

Box A: How could geopolitical events affect the Australian financial system?

The CFR has defined geopolitical risk as the potential for adverse impacts on the financial system from international tension, including trade restrictions, sanctions and conflicts. Geopolitical shocks can flow through the Australian financial system via a range of channels, some of which are well understood by regulators and industry and others that have added more complexity to risk management frameworks. The result is a wide range of potential adverse impacts on the system, including more traditional financial impacts to credit, liquidity or markets, operational disruptions that can lead to financial impacts, and newer risks such as foreign interference.

To understand the potential system-wide impacts of geopolitical events, APRA closely monitors three key transmission channels:

- Economic channel: Global conflicts and actual or perceived changes in economic policy can have significant effects on global trade. This could occur via the introduction of trade restrictions, such as tariffs, or a broader downturn in global economic activity. For countries like Australia that are deeply interconnected with global value chains and capital markets, a trade shock can be highly disruptive for certain businesses and industries and contribute to weaker domestic economic activity.

- Financial channel: Geopolitical events can have significant effects on global financial markets. This can include sudden changes in asset prices and greater volatility, as well as longer-term effects on confidence (risk aversion) if market participants feel that the future is more uncertain. Australian institutions, particularly larger institutions with a global presence, may experience volatility in the value of their investments and find it more difficult and more expensive to access funding.

- Safety and security channel: Geopolitical events can also adversely affect the safety and security of the financial system. Examples include damage to critical infrastructure, cyber-attacks and disinformation. The impacts on the financial system can be wide ranging and introduce newer types of risks such as foreign interference, sanctions enforcement and reputational impacts that need to be controlled.

The multifaceted nature of geopolitical shocks means that coordinated efforts are needed to mitigate threats and strengthen resilience. A focus for APRA in its supervisory engagements with regulated entities is strengthening considerations of the geopolitical environment into strategic planning, risk management frameworks, and routine monitoring and reporting. As part of this, APRA is looking to ensure management of traditional risks is robust, while increasing visibility of non-traditional risks. APRA is also working together with CFR agencies and industry to better understand and plan for geopolitical shocks and limit the impacts on the financial system.

Operational vulnerabilities have increased in a more digitally connected world, and a new prudential standard is helping to strengthen resilience.

Reliable access to financial services is essential for all Australian households and businesses. But sometimes, despite best efforts, these services can be disrupted or threatened, such as by an electricity or internet outage, or a cyber-attack. And because Australia’s financial system has, over time, become more interconnected, more dependent on digital technologies and more reliant on third-party service providers, an operational failure in one part of the system could have cascading effects across the entire system and undermine financial stability. Alongside geopolitical risks, cyber and operational risks are key concerns for the entities we regulate (Figure 1).

APRA plays an important role in ensuring that entities are well-prepared for operational disruptions so they can continue to provide the services Australians rely on. On 1 July 2025, a new prudential standard came into effect – Prudential Standard CPS 230 Operational Risk Management (CPS 230) – that introduced enhanced requirements for operational risk management across the entities APRA regulates. New obligations for banks, insurers and super funds include:

- identifying important business services and determining the extent to which these services can continue during severe disruptions;

- testing their business continuity planning to identify vulnerabilities so they are prepared to overcome severe disruptions; and

- enhancing third-party risk management by ensuring risks from material service providers are identified and appropriately managed.

APRA is engaging with entities – particularly the most significant financial institutions – to ensure they are meeting these new obligations.

Managing risks introduced by third-party service providers has been a particular focus for APRA. We are seeing that banks, insurers and super funds rely on many third-party service providers to deliver critical services throughout the technology supply chain. For example, some of the largest entities APRA supervises have around 150 material service providers on average supporting their critical operations. One of the risks APRA is highlighting is concentration, where many institutions rely on the same providers, which makes the system vulnerable to a single point of failure. In addition, we have seen that third parties can be used as a ‘backdoor’ to execute a cyber-attack on the financial system. Many service providers are also located overseas and outside the Australian regulatory perimeter. While CPS 230 enhances service provider oversight, APRA’s material service provider data collection will shed more light on this trend and inform the extent to which multiple institutions are relying on the same group of third-party service providers. APRA is also working closely with other CFR agencies and industry to develop a system-wide view of current and emerging operational vulnerabilities and to consider how we calibrate future oversight of critical third parties and the risks that they introduce to the financial system. This work includes exploring current and future policy settings and working collaboratively with other regulators to understand risk management practices in key cohorts such as critical infrastructure.

Disorderly adjustments in global financial markets could have destabilising effects on the Australian financial system.

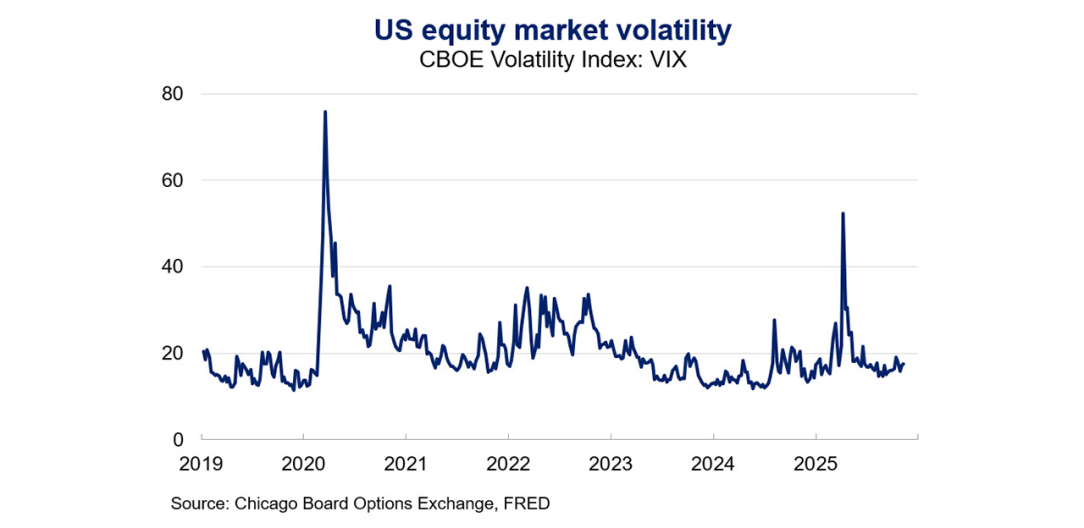

The uncertain and increasingly fragmented international environment has contributed to periods of significant volatility and abrupt price movements in global financial markets. The most notable of these was in April 2025, as market participants reacted to US tariff announcements and the unwinding of longstanding trade policies. The initial aftermath saw equity prices fall sharply, sovereign bond yields rise, and global currencies, particularly the US dollar, fluctuate. Some measures of volatility in financial markets spiked to levels not seen since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2

While the April episode was ultimately short lived, markets remain vulnerable to sudden corrections. This is particularly important to watch in an environment where many asset valuations are elevated compared to history and uncertainty about the future is heightened. Among the industries it regulates, APRA is seeing super funds having heightened exposures to these fluctuations in global financial markets. This has contributed to some volatility in returns and member asset values, but system-wide impacts have been limited, and super funds have managed the volatility well.

Another trend APRA is watching in global financial markets is rising yields on long-term sovereign bonds. Sovereign bonds are a form of debt instrument issued by governments to support public spending, and the return (yield) on these bonds fluctuates as investors weigh up the risk and return of sovereign bonds against other options. Yields also fluctuate in response to changes in the supply of bonds; for example, if governments are borrowing more and issuing more bonds, then yields tend to rise. In recent months, long-term sovereign bond yields for many advanced economies have hit decade highs amid concerns about the sustainability of government budgets, policy uncertainty and, in some countries, expectations of persistent inflation.

A global rise in bond yields and unease about the fiscal position of overseas governments can have flow-on effects for the Australian financial system. For example, higher bond yields can affect the cost of funding for Australian banks accessing offshore capital markets, which can in turn impact lending rates to Australian households and businesses. Insurers and super funds can also be impacted through their investments in sovereign bonds. In addition, governments in these more indebted countries may have reduced capacity to respond to economic and financial shocks, which can have implications for global financial stability.

APRA remains alert to conditions in global financial markets and their implications for the Australian financial system. We engage regularly with peer agencies on the CFR as well as international regulators and global standard-setting bodies to share information about exposures and factors that could amplify or dampen the effect of shocks.

Domestic developments

APRA is seeing: A strong and resilient financial system, but with the potential for vulnerabilities to build, especially in the housing market.

Risk environment

APRA judges that the domestic risk environment poses less immediate threat to the safety of the financial system than the international environment. That said, we continue to carefully monitor domestic developments to look for new and emerging risks. Our view of the domestic environment is shaped by our supervisory engagements, staff analysis and information sharing with peer regulators.

Domestic economy

Growth in the Australian economy is expected to pick up slightly over the second half of 2025 before stabilising. Interest rate cuts earlier in 2025 are expected to support spending by households and businesses. Inflation is substantially below its 2022 peak, but cost-of-living pressures remain for many households. The labour market remains strong by historical standards, but jobs growth is slowing from very high rates. Weak productivity growth is also a concern.

Legal & regulatory

In July 2025, APRA and other regulators received a letter from the Treasurer and Minister for Finance seeking specific, measurable actions to reduce compliance costs. In response, APRA set out nine initiatives that aim to minimise burden and support productivity, without compromising safety and stability objectives. By the end of 2025, APRA will have consulted publicly on five of these initiatives. Many of APRA’s actions are incremental – they build on existing proportionality in the framework – and we estimate these actions will moderately reduce the burden for the financial sector.

Technological

Digitalisation is transforming financial services, improving efficiency and customer experience. At the same time, it increases reliance on service providers, exposes the system and supply chains to disruption (including from cyber threats), and potentially creates lower financial inclusion for some groups. The rapid adoption of AI brings both opportunities and new risks.

Social

An ageing population is impacting how members engage with their superannuation and how policy holders engage with insurance. At the same time, younger generations born in the digital age are interacting with the financial system differently to previous generations and introducing new risks. For example, digital banking and the spread of news via social media channels could increase the speed of bank runs in some cases. High housing prices are posing an increasing challenge to home ownership for some groups in society.

Environmental

Australia is seeing changes in the frequency and severity of major weather events, which is impacting the affordability and accessibility of insurance. APRA’s Insurance Climate Vulnerability Assessment will explore how general insurance affordability may change over the medium term under two potential climate scenarios. The Australian Government recently published its new emissions targets for 2035, as well as Australia’s National Climate Risk Assessment.

Vulnerabilities

APRA is closely monitoring the build-up of domestic vulnerabilities, particularly in the housing market. This includes high household debt and high housing prices. We are also monitoring vulnerabilities outside of the housing market that relate to the structure of the financial system itself, particularly the growing interconnections between different parts of the system, such as super funds and banks. While not discussed in detail in this report, APRA is also alert to a range of other vulnerabilities such as preparedness for climate change and greater use of AI technologies.

Housing-related vulnerabilities are building.

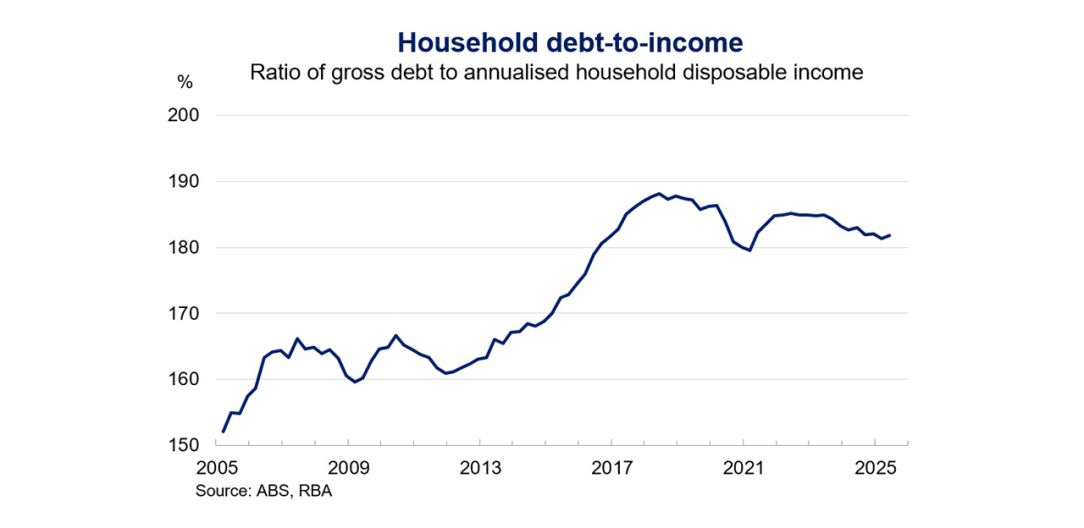

High household debt is a key vulnerability of the Australian financial system. Gross household debt relative to disposable income increased sharply in the 2010s, peaking at just under 190 per cent in 2018 (Figure 3). While it has eased a little in recent years to around 180 per cent, alongside stronger growth in nominal incomes, it remains high by historical and international standards. Highly leveraged households are more likely to encounter difficulties servicing their loans when economic conditions deteriorate. These households may need to cut back on their spending or even sell their property to meet their loan obligations, dynamics that can make downturns more severe and undermine the resilience of banks.

Figure 3

Housing price growth has strengthened since the start of the year. Lower interest rates have increased borrowing capacity for new mortgage borrowers, while the expansion of the Australian Government’s 5% Deposit Scheme is expected to boost demand from first home buyers. Given that housing supply takes some time to respond to increases in demand, momentum in housing prices is likely to continue in the near term. Higher housing prices generally come hand in hand with higher credit, as most households need to borrow to purchase their home or an investment property.

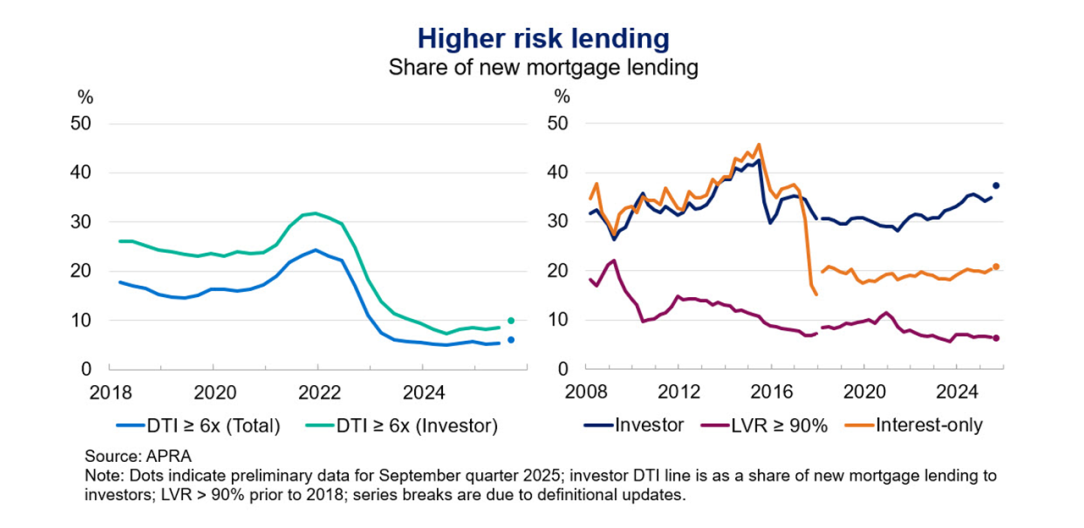

While overall housing lending standards remain sound, APRA is seeing some signs of higher risk lending picking up. The share of high debt-to-income (DTI) loans remains low overall, but there are signs of a pick-up among investors and at some banks (Figure 4). The share of investors in new mortgage lending more broadly has also risen, and investor credit growth has strengthened to its fastest pace in a decade. In addition, an increase in high loan-to-valuation ratio (LVR) loans is expected alongside the expanded 5% Deposit Scheme. Moreover, from its supervisory engagements APRA is seeing heightened competition for market share in housing lending, which could lead to pressure to ease underwriting standards and increase risk appetite. For example, APRA has observed that some banks have increased appetite to make lending decisions for certain customer cohorts that are exceptions to their internal lending policies.

Figure 4

In aggregate, both borrowers and lenders exposed to the housing market have maintained a high level of resilience. Lower inflation and interest rates have eased financial pressures on borrowers, and many households are continuing to build cash buffers. Non-performing loans also remain low, supported by lower interest rates and positive real wages growth, and current and forecast levels of banks’ capital and liquidity remain above APRA’s requirements. A long period of prudent lending standards has also supported banks’ resilience.

However, this resilience could be eroded over time. For example, if lower interest rates (which tend to increase borrowers’ demand for loans) coincided with a deterioration in lending standards, this could lead to a rise in risky lending. Household debt may increase further, and some households may struggle to manage their repayments. If an economic shock occurred in that environment, this could result in higher default levels and credit losses for banks. APRA and the CFR agencies are carefully monitoring these dynamics. In addition, APRA has been engaging with the lenders it regulates to ensure a range of macroprudential policy tools can be implemented where needed (Box B).

Box B: What is macroprudential policy and how does it support financial stability?

The objective of macroprudential policy is to promote financial stability. APRA uses its macroprudential toolkit to adjust its prudential requirements for banks in response to changes in the financial cycle.

Because macroprudential policy aims to address system-wide risks, it is calibrated on an industry-wide or cohort basis. APRA aims to apply macroprudential policy in a countercyclical way, which means these policies help the system build resilience during good times, and guard against excessive risk-taking. They can also provide flexibility in times of stress and can be adjusted or removed as risks subside.

APRA has a range of macroprudential tools it can use to target different types of risks and vulnerabilities. To date, APRA has mainly relied on two types of tools:

- Capital measures: These can be used to adjust the amount of capital banks are required hold. For example, APRA is responsible for setting a ‘countercyclical capital buffer’ for Australian banks, which is designed to protect the banking system against potential future losses. This buffer can vary between 0 and 3.5 per cent of banks’ risk-weighted assets and is currently set at its default rate of 1 per cent. Releasing this capital in a downturn can allow banks to continue to support the economy through lending to households and businesses.

- Credit measures: APRA can also set limits on certain types of risky lending and minimum criteria that banks need to apply when assessing a borrower’s repayment capacity. For example, when banks originate new housing loans, banks need to assess new borrowers’ ability to meet their housing loan repayments at an interest rate that is at least 3 percentage points above the loan product rate. This ‘mortgage serviceability buffer’ provides an important contingency in the years ahead for rises in interest rates or unforeseen changes in a borrower’s income or expenses.

More details about these tools can be found in our Macroprudential Policy Framework.

In deciding what the appropriate macroprudential policy settings should be, APRA takes a forward-looking approach and draws on a range of indicators of system risk. Some of these indicators include trends in credit growth and leverage, growth in asset prices, lending conditions and the financial resilience of banks. APRA consults with peer regulators on the CFR about the macroprudential risk environment and before making any changes to its macroprudential settings. In support, the RBA also provides financial stability advice to the CFR and APRA.

APRA has recently engaged with regulated entities on implementation aspects of lending limits for residential mortgage lending, including limits on high DTI, investor or interest-only lending, to ensure these tools can be activated in a timely manner where needed.

While regulated entities are judged to be resilient, a more interconnected financial system increases the risk that shocks can have system-wide impacts.

APRA currently regulates 1,147 entities holding over $9.8 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members. This is almost double the total assets regulated in 2014-15. Through its supervisory assessments, APRA is seeing continued strong financial resilience in regulated entities due to maintenance of capital levels above regulatory requirements, stable liquidity, and strong parental backing for overseas-owned insurers. Further strengthening of recovery and exit plans remains a focus for APRA. Another focus in the current environment is lifting operational and cyber resilience, particularly in the superannuation industry.

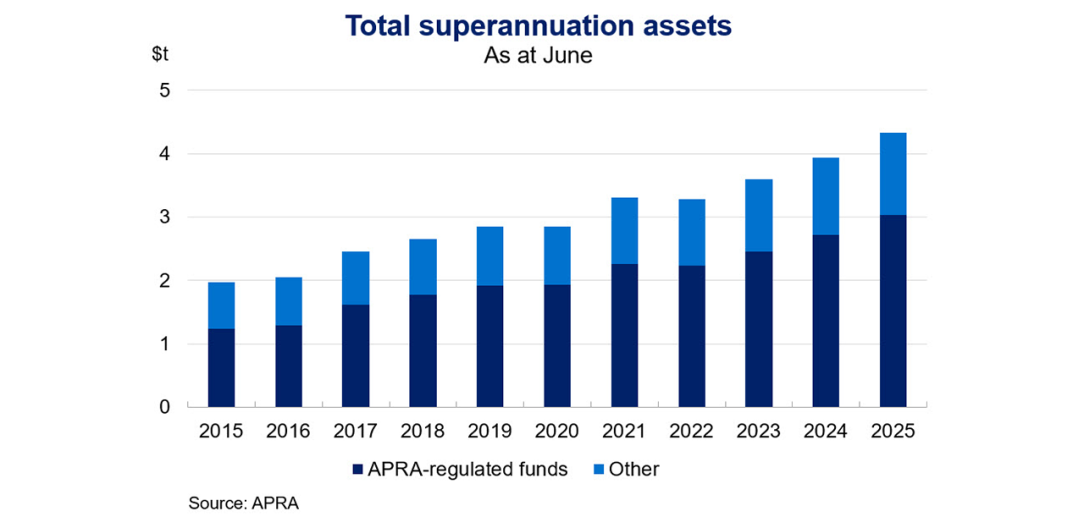

The superannuation industry has become a larger component of the Australian financial system over time, and it has historically played an important role in keeping the financial system stable during stress. The value of assets managed by the superannuation industry has doubled over the past decade to $4.3 trillion in June 2025, with around two-thirds of those assets ($3.0 trillion) being managed by APRA-regulated funds (Figure 5). Some of the structural features of super funds – like long-term investment objectives, restrictions on borrowing to invest, and steady inflows from compulsory member contributions – mean that the industry acts as an important stabiliser for the system during stress. In many ways, this also makes Australia’s superannuation industry different to how some large pension funds overseas are structured.

Figure 5

At the same time, the superannuation industry’s growing importance in the system has seen it become more interconnected across the system. Some of these linkages are financial, such as investments in bank debt and equity, while others are non-financial, such as relying on a small group of third parties to deliver critical services. While these links can make the system more efficient, they can also amplify stress in some scenarios. A focus for APRA is testing how these interconnections could dampen or amplify stress, including with our first system risk stress test (Box C). Strengthening super funds’ investment governance practices and operational resilience are other areas of APRA’s supervisory focus.

APRA, in collaboration with the CFR agencies (particularly ASIC), continues to assess the implications to the Australian financial system of growing activity by financiers that are not prudentially regulated. These entities, notably non-bank lenders, private credit firms and private equity providers, can play an important role in the system, such as providing competition, tailored wealth-building or financing solutions not otherwise available. However, not being prudentially regulated, these entities also have greater opportunity to take on higher risk business. Their business models are less transparent and, at a whole-of-system level, potentially increase aggregate leverage in a way that is not well captured by official data collections – a common international concern. As this private market activity increases both in Australia and internationally, there is also growing interconnection with APRA’s prudentially regulated institutions. This growth in leverage and interconnection can amplify financial system vulnerabilities.

APRA is focused on assessing potential risks to regulated industries arising from their interconnections with these financiers and is monitoring international developments closely. While opaque data and reporting standards present challenges, supervisory liaison illustrates that regulated entities are already evaluating potential risk implications, such as increasing competition and exposure concentrations.

Although these non-prudentially regulated entities presently account for a small share of Australian financial system activity and this sector is not seen as posing a significant threat to financial stability at this stage, the sector is growing and warrants attention. Over the past year, APRA has reinforced expectations on valuation governance, investment governance, and liquidity risk management for superannuation funds investing in unlisted assets and is consulting with life insurers on the capital treatment for unrated investments. APRA is continuing to direct supervisory attention to this area, assessing the risks and, as necessary, responding to them.

Box C: Phase 1 of APRA’s system risk stress test

Stress testing is a forward-looking assessment of how financial institutions can withstand adverse conditions. This is done by estimating the impacts of ‘severe but plausible’ economic downturns or other adverse events on an institution’s profitability, asset quality, capital and liquidity. The results of stress tests provide insights into risks, vulnerabilities and resilience in the financial system.

In 2025, APRA is undertaking its first exploratory system risk stress test. While APRA regularly conducts stress tests for single industries, the system risk stress test is designed to explore how key risks to the financial system could transmit across industries, particularly between banking and superannuation. Four large banks and six large super funds are participating, representing around 70 per cent of the banking industry and 45 per cent of APRA-regulated super funds. The exercise is being run over two phases: this box highlights some key findings from Phase 1.

In Phase 1, participants in the stress test were asked to consider the impact of a ‘severe but plausible’ shock in financial markets and the domestic economy, as well as an operational disruption. The scenario also included some idiosyncratic factors that affected banks and super funds differently. The stress scenario itself was 12 months in duration and was designed in consultation with industry. It assumed no change in government policy or exceptional support.

APRA has analysed responses from the first phase of the stress test, with five key findings:

- The superannuation industry was able to maintain enough cash and liquid assets to meet requests from members and other obligations during the stress. However, in doing so super funds needed to make significant changes to their asset portfolios, and this rebalancing had a disproportionate impact on some members.

- Banks experienced significant liquidity stress because of a large and sudden withdrawal of deposits and other forms of funding. This included withdrawals by super funds. However, each bank was able to demonstrate actions that ensured they could restore liquidity levels and continue to meet their financial obligations when due.

- Participants’ responses to restore liquidity levels had some impact on markets. For super funds this included large transactions in international and domestic listed assets, with limited transactions in unlisted assets. There was also a relatively modest impact on foreign exchange margins and settlement in the scenario.

- Despite experiencing their own financial pressures, super funds were able to continue to provide capital needed to support the solvency of banks in the scenario. The methods and approaches of responding differed across super funds depending on their business models and internal structures.

- The operational shock exacerbated the impact of the stress. The shock meant that banks and super funds were unable to trade securities for a period of time. The impact was greater on banks as it coincided with their liquidity stress in the scenario. Super funds were relatively less impacted, but the exercise highlighted areas of development in their operational responses.

In addition to the findings above, the exercise highlighted the benefits of conducting exploratory scenarios at the system level. For example, APRA saw a wide range of assumptions applied by entities to the scenario that varied both within and between industries. This included a variation in expectations about how other counterparties would respond in stress. Several participants also told us that the exercise will be used to inform aspects of their own internal stress testing programs.

APRA is currently finalising the design of Phase 2 of the exercise. Phase 2 will provide an opportunity to test the robustness of the Phase 1 findings and to consider other areas of analysis. APRA expects to publish a final detailed report of the findings of the system risk stress test, incorporating Phase 2, in mid-2026.