Activating debt-to-income limits as a macroprudential policy tool

Summary

APRA’s macroprudential policies play an important role in promoting financial stability. They can build resilience and lean against excessive risk-taking in episodes when financial risks are growing. APRA has a number of tools available to help manage different aspects of macroprudential risk. Currently active tools include:

- the countercyclical capital buffer, which builds resilience in the banking sector and can provide additional flexibility to support the provision of credit in significant downturns; and

- the serviceability assessment buffer, which builds additional resilience for individual new loans and so, over time, in lenders’ housing loan portfolios to help withstand future stress.

The available toolkit also includes limits on riskier forms of lending, such as high debt-to-income (DTI), high loan-to-valuation (LVR), interest-only and investor loans. While such limits are not currently active, APRA has used limits on specific types of lending in the past to respond to changes in financial system risks.

Recent declines in interest rates and a tight labour market suggest a shift in the financial risk cycle. These periods often coincide with periods of higher credit growth, rising household indebtedness and riskier lending activity, including – as seen most recently in 2021 – high DTI lending. High DTI lending is a form of riskier lending that adds directly to household indebtedness. This macroprudential risk has been the focus of discussion at Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) meetings over the past year.1 As the CFR has noted, it is important to be ready both to respond to immediate risks and to prevent vulnerabilities building in the financial system over time.

While overall bank lending standards remain sound, APRA has observed a pick-up in some riskier forms of lending over recent months as interest rates have fallen, housing credit growth has picked up to above its longer-term average and housing prices have risen further.

Combined with a resilient labour market, these trends suggest a shift in the financial risk cycle and a potential build-up of vulnerabilities that could undermine banking sector and household financial resilience if left unchecked. In particular, high DTI lending has started to pick up, albeit from a low base, driven by high DTI loans to investors. This is expected to increase further in this part of the cycle, and already high household indebtedness could increase further.

Given these dynamics, APRA is now activating a DTI lending limit on residential mortgage lending as a macroprudential tool to prevent the potential build-up of housing-related vulnerabilities. The limit – effective from February 2026 – allows up to 20 per cent of authorised deposit-taking institutions’ (ADIs) new mortgage lending to be at a DTI greater or equal to six times. The limit will apply to ADIs’ owner-occupier and investor portfolios separately. Within the limit, banks retain discretion to lend to creditworthy high DTI borrowers, in line with their own risk appetite and lending policies.

By activating the DTI limit now, APRA is seeking to pre-emptively contain the build-up of system-wide risks and strengthen banking and household sector resilience. Moderating high DTI lending early will allow sound credit growth to continue to support activity of households and businesses with little disruption. Importantly, a 20 per cent limit is unlikely to restrict lending to owner-occupiers or first home buyers in the near term, as these borrowers typically have lower DTIs. For investors, while high DTI flows are picking up, high DTI lending is currently well below the limit for the ADI sector as whole and is expected to be near the limit for only a small number of individual ADIs. This means the limit is not expected to have a near-term impact on borrowers’ access to credit. Based on past experience with lending limits, we expect the costs of activating a DTI limit now to be less than at a time when high DTI lending is much stronger. Helping safeguard financial stability in this way supports economic growth and productivity.

The DTI limit is intended to prevent an unsustainable rise in household indebtedness during episodes of heightened risk, while not overly constraining credit supply at other times. While some increase in higher DTI lending is expected as lower interest rates lift borrowing capacity, the limit will manage the possible build-up of risk in housing credit by setting guardrails for the growth of new high DTI loans by individual lenders.

APRA will provide ADIs with exemptions from the DTI limit for bridging loans for owner-occupiers and loans for the purchase or construction of new dwellings. This will enable the smooth functioning of property transactions and avoid constraining incentives for the supply of new housing. While the lending limit will apply to all banks, there will be some proportionate treatment for smaller banks (non-Significant Financial Institutions (SFIs)) so that they can apply the limit in a way that smooths through periods of volatility, as well as providing a longer implementation period, if needed, and an option to not apply the exemptions described above.

APRA has also examined closely whether broader investor limits are warranted. To date, we have not observed signs of a material build-up in vulnerabilities that we have seen in some past episodes of strong investor activity such as in 2014.2 As highlighted by the Reserve Bank in its latest Financial Stability Review, while housing prices and credit have increased, this has so far been consistent with the historical experiences of previous interest rate easing cycles. APRA will continue to assess carefully the evolving risk environment related to housing lending and will consider additional limits, including investor-specific limits, if macro-financial risks rise significantly or lending standards deteriorate.

APRA will be actively monitoring and engaging with lenders to ensure the DTI limit is working as intended and, if appropriate, adjust settings. APRA will also closely monitor any spillover effects, including shifts of lending activity toward non-ADI lenders, to ensure the limit is achieving the intended objective of managing system wide build ups in risks. If needed, APRA has powers to apply macroprudential measures to non-APRA regulated lenders, where these lenders are materially contributing to financial stability risks, although it has not used them to date.

APRA considers the introduction of DTI limits as a complement to its existing active macroprudential tools. Currently those settings are the mortgage serviceability buffer and counter-cyclical capital buffer, which - reflecting the potential for rising macroprudential risks - remain steady at 3 per cent and 1 per cent of risk-weighted assets, respectively.

Next steps and implementation settings

APRA has today written to all ADIs requiring that, from February 2026, they limit residential mortgage lending with a DTI ratio greater than or equal to six to 20 per cent of all new mortgage lending. The limit will apply to ADIs’ owner-occupier and investor portfolios separately and will be measured on a quarterly basis.

Bridging loans for owner-occupiers and loans for the purchase or construction of new dwellings will be exempt. Bridging loans are temporary and so do not tend to add to system risk in the way other high DTI loans do. Loans for the construction and purchase of new dwellings are important for facilitating the building of new housing supply. Since an increase in new supply can mitigate house price rises (and so credit and debt) this exemption may – at the margin – help to contain vulnerabilities related to rising household indebtedness.

In setting the DTI limit, APRA incorporated several features that mitigate potential negative impacts on competition. For example, the limit applies only to new lending of ADIs and does not depend on the size of their existing loan books. Moreover, activating the limit before it becomes binding is expected to mitigate customer impacts. In designing the limit, APRA has also engaged with industry stakeholders and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and proportionality has been a central consideration in the application of the limit to mitigate potential competition impacts. As with any new tool, the effect on competition will need to be carefully monitored over time.

Historically, smaller ADIs have originated materially lower flows of investor and owner-occupier high DTI lending than larger ADIs. Nonetheless, there is a risk that smaller ADIs may be subject to heightened demand for (and more volatile flows of) high DTI lending as the limit begins to restrict the lending behaviour of larger ADIs.

To achieve a proportionate approach across all ADIs, APRA will:

- apply a 4-quarter rolling measurement to non-SFIs;

- provide a longer implementation period for non-SFIs, if needed; and

- provide non-SFIs with the option not to apply exemptions in their reporting, to streamline data and monitoring.

Activating a debt-to-income lending limit

Activating a new macroprudential policy tool

APRA’s macroprudential policy tools aim to mitigate financial stability risks at the system-wide level.3 They seek to promote a safe and stable financial system that enables households and businesses to borrow confidently, save and invest for the future. Macroprudential policy plays a role in promoting financial stability through the financial risk cycle, with a particular focus on housing lending and household indebtedness. It can lean against excessive risk-taking when financial risks are building and provide support to the financial system in episodes of extreme risk aversion where the flow of credit is often disrupted. Macroprudential policy tools are a complement to APRA’s prudential policy and supervision activities.

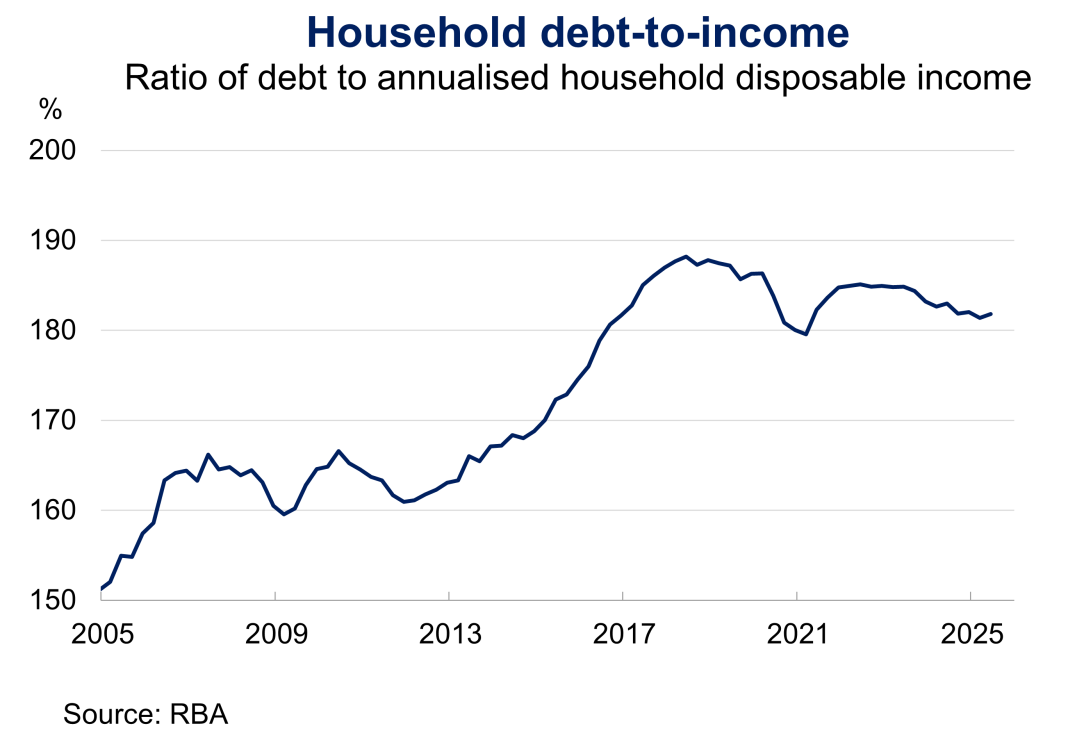

High household indebtedness is a key vulnerability in the Australian financial system. Over the past two decades, aggregate household indebtedness has increased from around 155 to 180 per cent and is much higher than in many of Australia’s peer economies. Highly indebted households are more likely to encounter difficulties servicing their loans when economic conditions deteriorate, undermining financial resilience of the system.

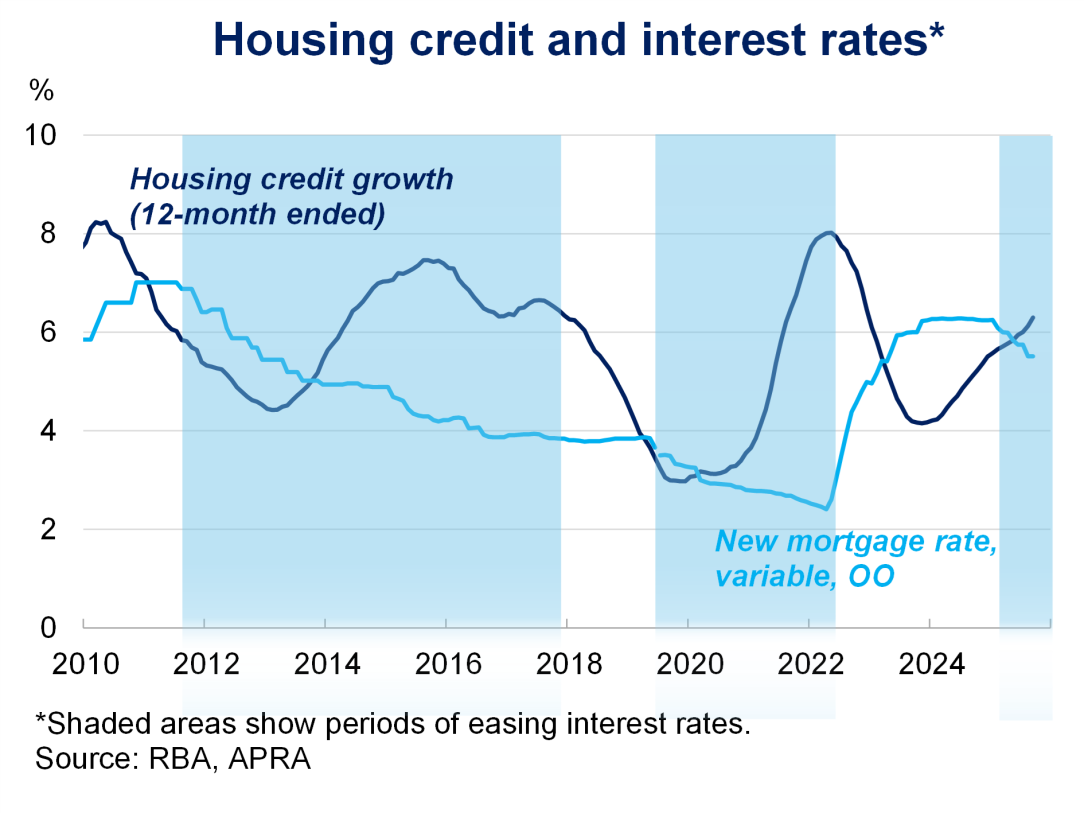

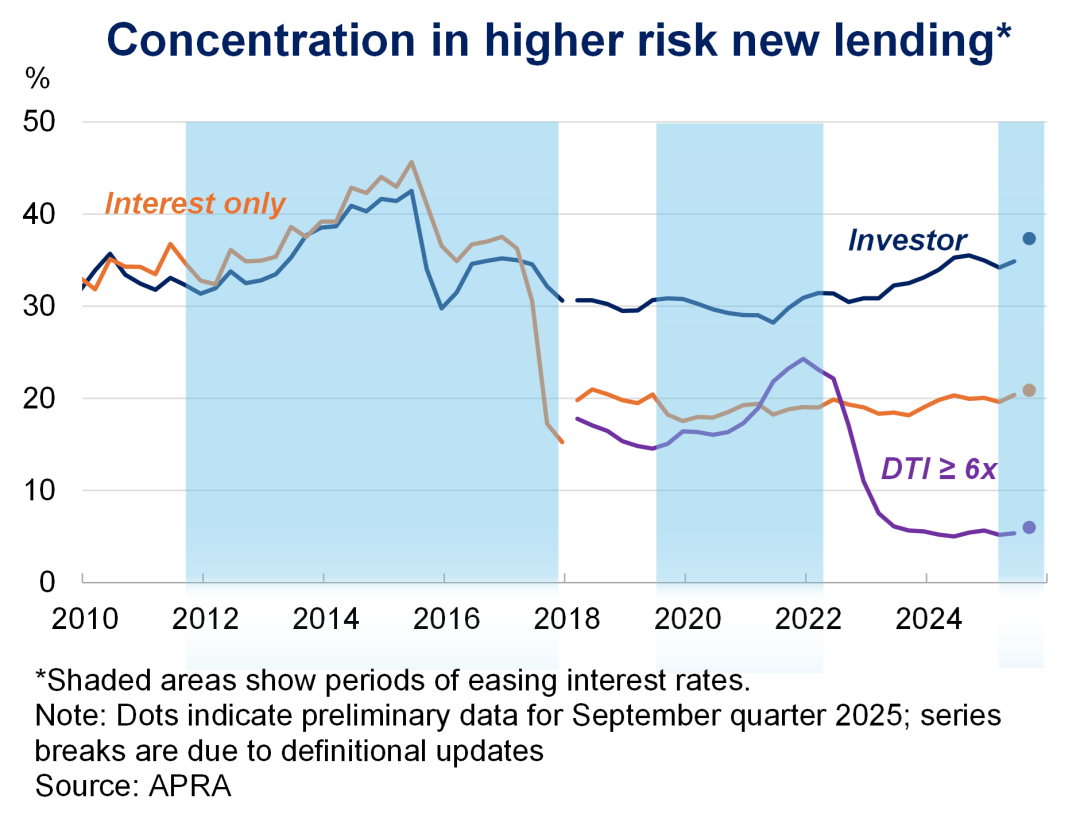

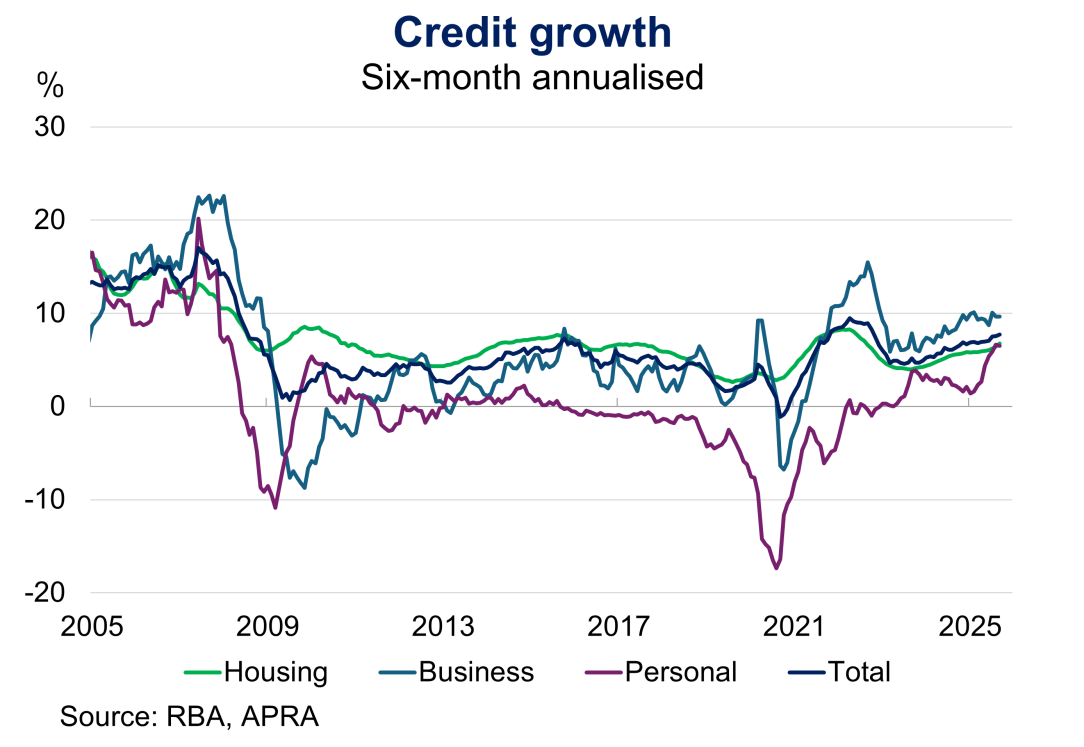

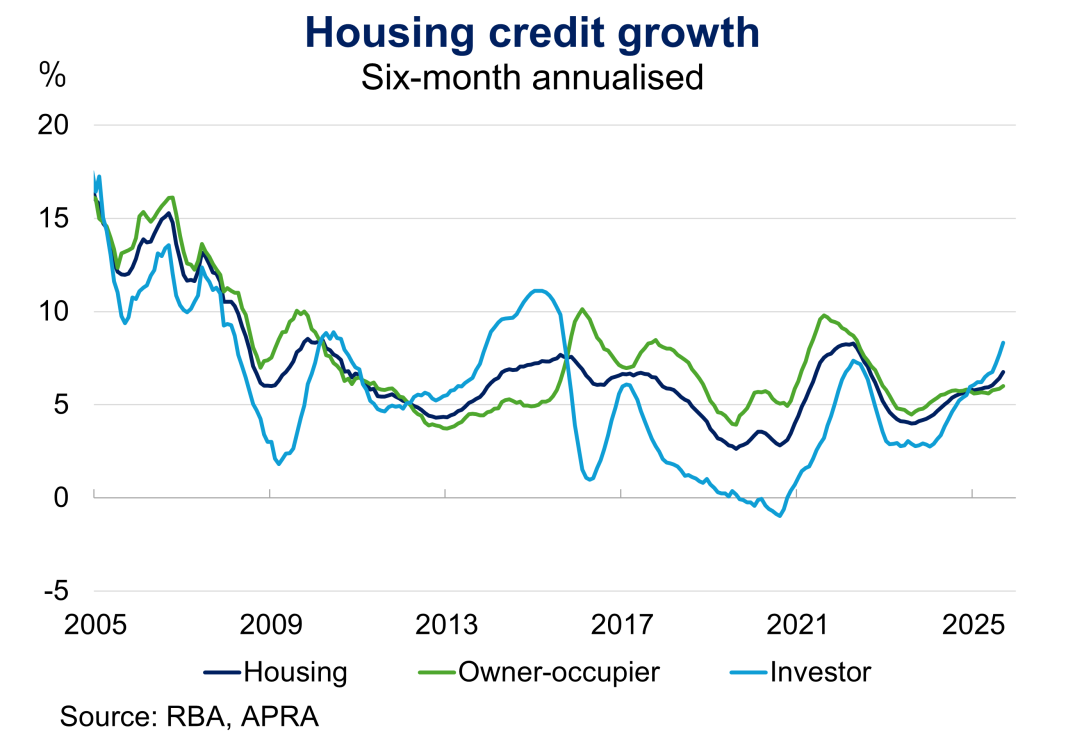

Housing-related vulnerabilities can build rapidly in certain periods of the financial risk cycle. For example, in Australia, periods of falling and/or low interest rates are associated with the build-up of housing risks and strong credit growth (Graph 1). These periods, when credit and housing prices have been growing strongly, have often been associated with strong growth in lending to high DTI borrowers, investors or for interest-only loans.4 This has been the case in episodes such as 2014-15, as well as most recently in 2021-22 (Graph 2).

Graph 1

Graph 2

To respond to such macroprudential risks, APRA has used a variety of policy tools in the past, depending on the type of risk present. In 2014 and 2017, APRA introduced measures which limited growth in banks’ lending to investors and the concentration of interest-only loans in new lending. This was in response to an environment characterised by high and rising household indebtedness and housing prices, subdued income growth and low interest rates, with concerns that bank lending practices were amplifying these risks. In 2021, APRA raised its expectation for a sound serviceability buffer in housing lending to mitigate risks from borrowers overstretching in an environment of very low interest rates and rising house prices. At the time, APRA asked ADIs to be pre-positioned for an activation of DTI limits, if needed. In August 2025, APRA engaged with industry to ensure a range of lending limits, including high DTI limits, could be deployed in a timely manner if needed.

Why APRA is activating a DTI lending limit now

In recent years, credit risks in the Australian financial system have remained contained. Despite rising cost of living pressures and a sharp rise in interest rates, housing non-performing loans have remained low, supported by a strong labour market. Growth in housing credit has remained robust over this period, despite household financial pressures, and mortgagor households maintained strong cash buffers overall.

The current dynamic in the financial cycle does however signal a potential pick-up in household indebtedness and growth in riskier forms of lending. Recent discussions at CFR meetings have also highlighted this risk, and how it could be best managed. At a time where financial stability risks in the housing sector are building, APRA’s approach to macroprudential policy needs to be forward-looking, robust, and focused on managing risks in the outlook associated with high household indebtedness.

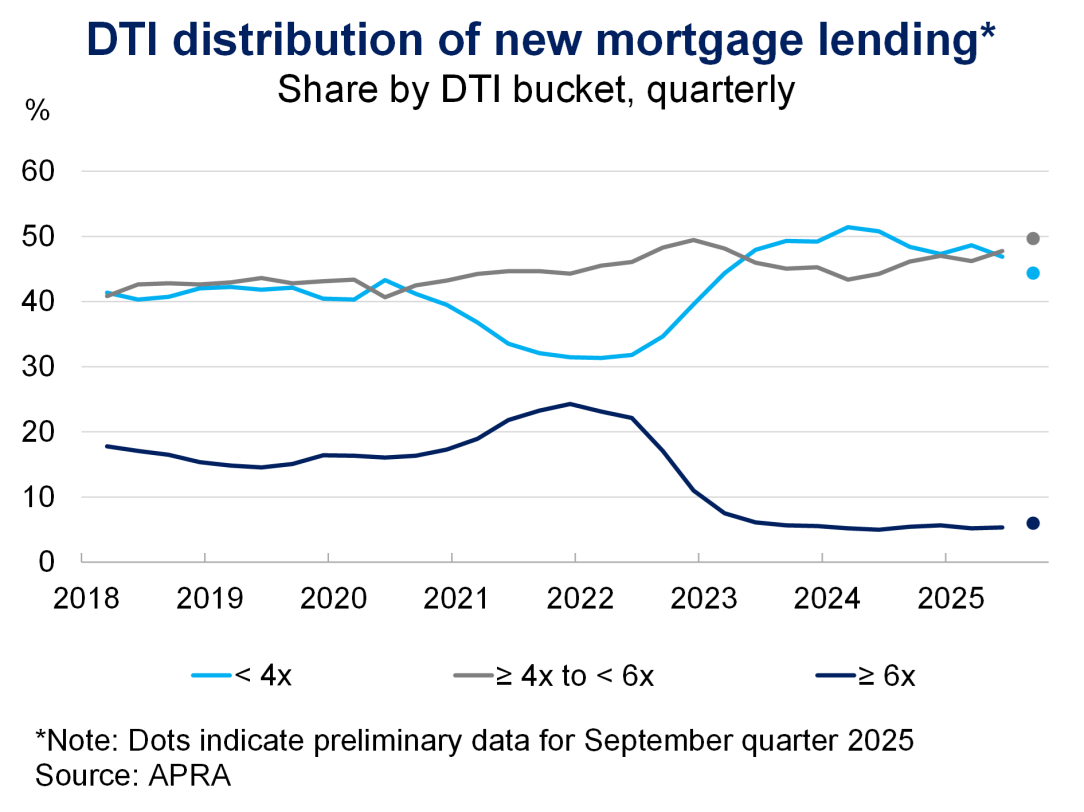

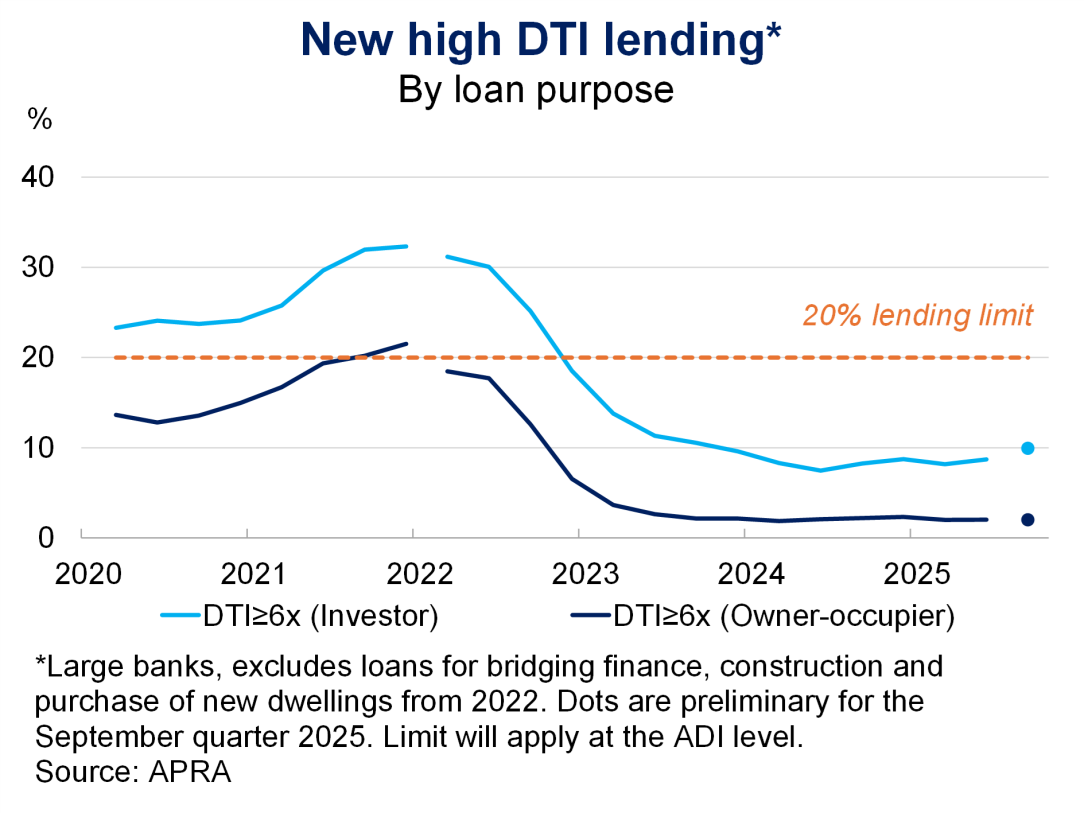

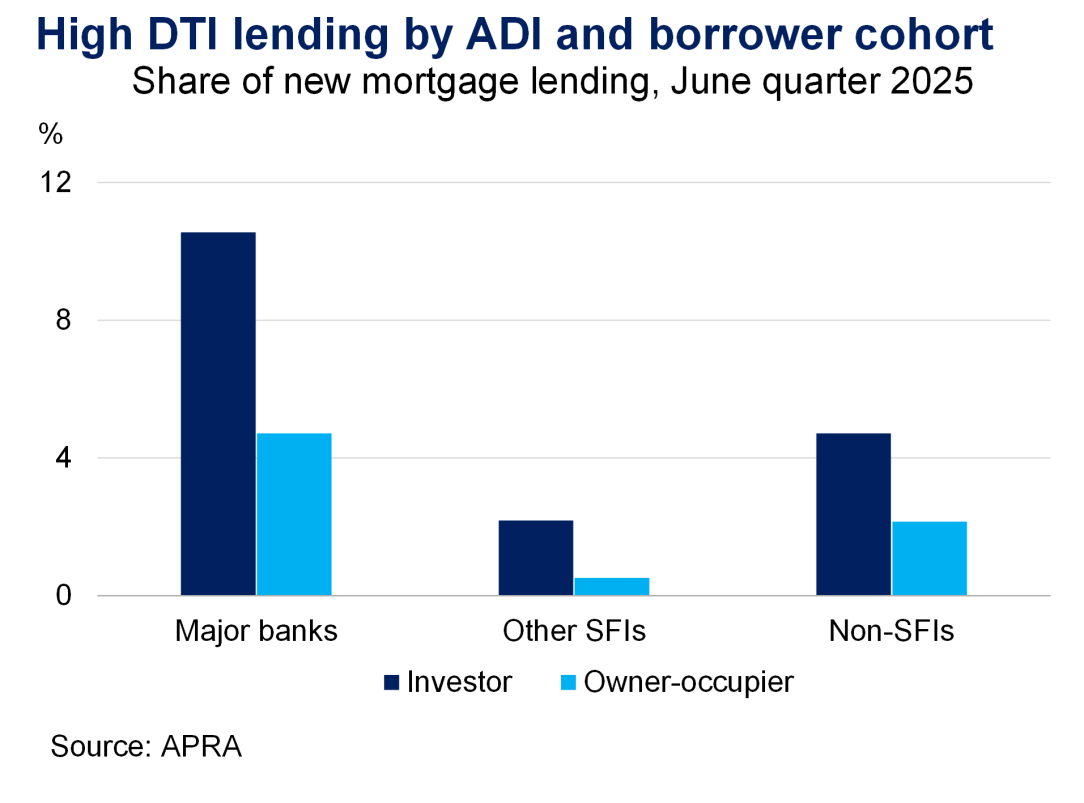

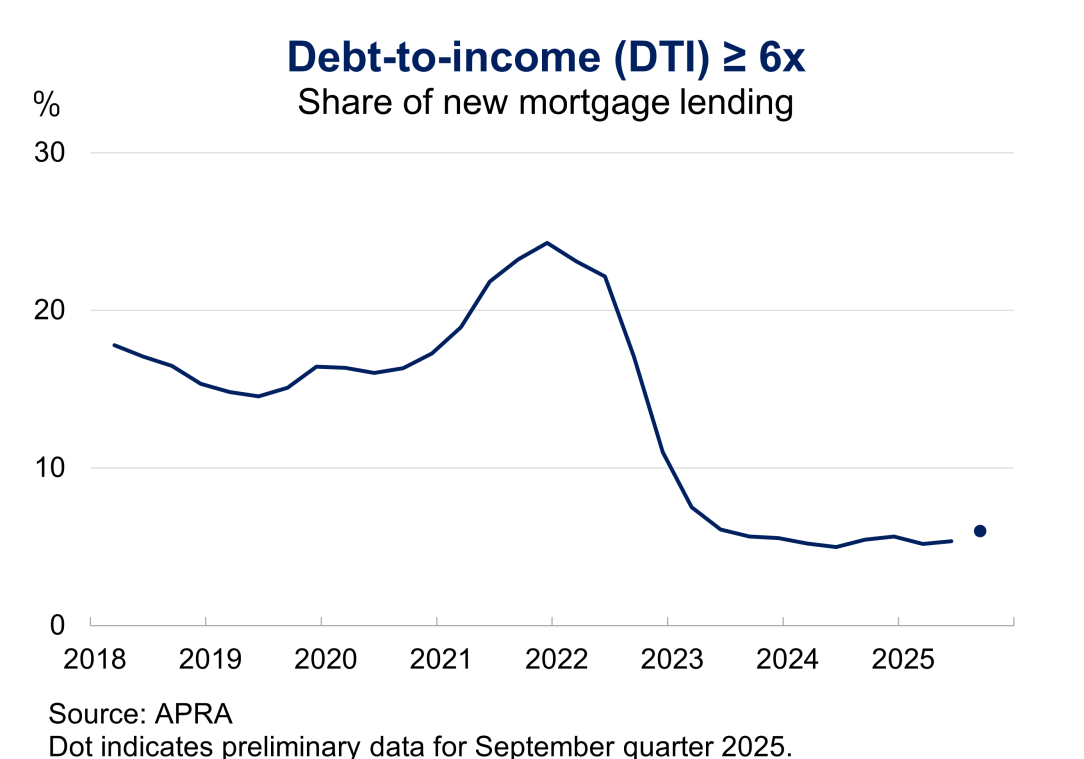

While broad lending standards remain sound, there are signs of a pick-up in high DTI lending (Graph 3). While high DTI lending in aggregate remains low, this masks a pick-up in high DTI lending to investors in the September quarter to around 10 per cent of new investor loans, the highest since 2023 (Graph 4). Lending has also migrated from the loans with DTI below 4 to those with DTI between 4-6, leading to an increase in average DTIs (Graph 3).

Graph 3

Housing credit growth has increased to above its post-GFC average and housing prices are strengthening from already high levels. The pick-up in housing credit has been largely driven by strength in investor credit growth, which is growing at its fastest pace in a decade. While investor loans are typically not riskier in terms of default rates, strong investor credit growth has in the past been associated with macro-financial risks – such as aggregate household indebtedness – rising more broadly in the economy, particularly in low interest rate environments. At this stage we do not see investor activity eroding broader lending standards or contributing to rising household indebtedness. As highlighted by the Reserve Bank in its latest Financial Stability Review, the increases in housing prices and credit so far have been consistent with the historical experiences of previous interest rate easing cycles. Signs of increases in riskier lending have been contained to high DTI investor lending.

APRA’s limit on high DTI lending will apply on ADIs’ owner-occupier and investor portfolios separately. The introduction of a DTI lending limit on investor lending now will help mitigate potential risks stemming from this riskier segment of investors borrowing at high DTIs. Across all ADIs, the share of new lending to investors with high DTI increased from 8 per cent to around 10 per cent of new lending over the year to the September quarter 2025 (Graph 4). Currently, a small number of ADIs are estimated to be near or at the DTI limit of 20 per cent (once the exempted loan types are taken into account). For owner-occupiers and first-home buyers, a DTI lending limit of 20 per cent is unlikely to restrict lending to these cohorts in the near term, given they typically borrow at lower DTIs than investors.

Why APRA is implementing a DTI limit pre-emptively

In response to previous episodes of housing market exuberance, APRA introduced temporary limits on ADIs’ investor (2014) and interest-only (2017) lending.5 While these measures were effective in curbing those types of lending, a key reflection was that restricting risky lending, once already elevated, could cause significant business disruptions.

Introducing a DTI limit now provides a forward‑looking safeguard, reducing the likelihood that current credit dynamics translate into a material build‑up in housing-related vulnerabilities. This measure complements existing serviceability requirements to help maintain resilience in the financial system if housing market momentum continues.

Past experience with lending limits suggests that the costs of activating a DTI limit now will be lower than once there is a broad-based rise in high DTI and other risky lending already under way. Acting pre-emptively by using DTI limits strengthens resilience in the banking and household sectors for known vulnerabilities and risks, especially from the investor cohort. Further, implementing in a pre-emptive way allows sound credit growth to continue, while helping safeguard financial stability to support economic growth and productivity in the long run.

Using DTI limits as a macroprudential tool, and in a pre-emptive way, is also in line with international best practice, as has been highlighted by recent reports from the International Monetary Fund and Committee on the Global Financial System.6 Several peer jurisdictions have introduced income-based macroprudential policy measures (such as loan-to-income (LTI) or DTI lending limits) on an ongoing basis (Table 1). For example, LTI limits have been used in the UK and in Ireland for many years, while DTI limits are part of the active toolkit in New Zealand and Norway.

Table 1: International Comparison of LTI or DTI Limits Currently in Use

| Peers | LTI / DTI Limits | Year introduced | Implemented pre-emptively? | Debt ratio threshold* | Flow limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | LTI | 2025 | Yes | 4.5x | Institution-specific |

| Ireland | LTI | 2015 | Binding upon implementation** | 3.5x – 4x | 15%

|

| New Zealand | DTI | 2024 | Yes | 6x – 7x | 20% |

| Norway | DTI | 2017 | Binding upon implementation** | 5x | 10%, subject to other conditions |

| UK | LTI | 2014 | Yes | 4.5x | 15% |

Source: OSFI; CBOI; RBNZ; Norges Bank and BOE * Debt ratio level varies by sub-portfolio (e.g. investor, owner-occupier, first-home buyer) where a range is indicated. UK calibration is currently under review. | |||||

APRA considered the costs and benefits of activating several alternative tools in its macroprudential framework to mitigate a future build-up in household indebtedness, such as LVR limits, investor lending limits and an increase to the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB). APRA considers at this time that DTI limits are the best option for managing potential vulnerabilities. While LVR limits can be a useful tool in uplifting the resilience of lenders, there is evidence that LVR limits disproportionately constrain lending to First Home Buyers (FHBs). Raising the CCyB can provide lenders with additional flexibility to continue lending to households and businesses in a downturn. However, the CCyB has long lead times and evidence for its effectiveness in dampening the build-up of indebtedness in an upswing is limited. While investor lending limits have proven effective in dampening indebtedness in previous cycles, APRA considers DTI limits a more targeted way of addressing any further build-up in this vulnerability at this time, as outlined above. As noted above, however, should signs emerge of a material build-up in vulnerabilities driven by strong investor growth, APRA would consider the use of additional, investor-focussed lending limits.

How DTI lending limits help manage macroprudential risks

The DTI limit will restrict ADIs’ shares of new residential mortgage lending to borrowers with high DTI ratios. The limits will apply to new lending and not to existing borrowers. Under the limit, each ADI can lend, on a quarterly basis, up to 20 per cent of new owner-occupier loans and up to 20 per cent of new investor loans to borrowers with a DTI ratio greater than or equal to six (Graph 4).

Graph 4

A 20 per cent DTI limit on investor lending would have been binding in 2020-22 when interest rates were low (Graph 4). In 2021-2022 when risks from rising housing indebtedness were building rapidly, a 20 per cent limit would have reduced the concentration of new high DTI lending for both owner-occupiers and investors, and hence the build-up of this form of riskier lending.

The limit on high-DTI investor lending will help limit the extent to which highly indebted investors amplify the financial cycle, without unduly restricting broader investor activity. While high DTI investor flows are picking up, the limit is expected to bind in the near term only on a small number of ADIs and not at the system level. The limit on high-DTI owner-occupiers is unlikely to constrain owner-occupiers in the near-term given significant headroom to the 20 per cent limit (see graph above).

Lenders have flexibility in how they can manage lending to stay within the limit. They can accommodate new high DTI borrowers if they have not reached their cohort’s concentration limit for a specific reporting period. If a new borrower requests a high DTI loan that would risk exceeding the limit, the lender could offer a lower DTI loan or defer the application to a later time. Borrowers may also seek credit from different lenders that are not close to exceeding the limit.

APRA considers the introduction of the DTI limit as a complement to its existing macroprudential tools, including the serviceability buffer, which provides an important contingency for shocks to a borrower’s ability to service their loan that may otherwise result in default. As part of its ongoing assessment, APRA will consider the settings of all active macroprudential tools once the DTI limit comes into effect, taking into account the risk environment.

Engagement

In July 2025, APRA announced its intention to engage with entities on the implementation aspects of different lending-based macroprudential tools. APRA has completed its engagement with industry, which provided valuable insights. This has informed the design of the DTI limit.

Over the past year, APRA has engaged actively with the CFR to assess risks in the housing market and consider possible lending limits to contain them. In determining its approach APRA has also considered the impacts on competition and engaged with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. APRA recognises that lending limits can influence competition in the mortgage market and this needs to be balanced against the financial stability benefits of these tools. In setting the DTI limit, APRA incorporated several features that mitigate negative impacts on competition. For example, the limit applies only to new lending of ADIs and does not depend on the size of their existing loan books. Moreover, activating the limit before it becomes binding is expected to mitigate customer impacts. Proportionality has also been a central consideration in the application of the limit to mitigate potential competition impacts. As with any new tool, the competition impact needs to be monitored over time.

The impact of the DTI limit will vary across lenders, but the limit is not expected to disproportionately affect smaller ADIs. Historically, larger ADIs have originated materially higher flows of high DTI for both investor and owner-occupier lending than smaller ADIs (Graph 5). Nonetheless, there is a risk that smaller ADIs may be subject to heightened demand for high DTI lending as the limit begins to restrict the lending behaviour of larger ADIs.7 Further, many smaller ADIs may have more volatile flows of lending, including at high DTI. APRA will closely monitor any spillover effects, including increased high-DTI lending at smaller ADIs or shifts toward non-ADI lenders, to ensure the limits are achieving the intended objective of managing system wide build-ups in risks.

Graph 5

APRA looked carefully at the calibration of the DTI limit based on analysis of historical data and of individual banks, taking into account management buffers and lending limits implemented by peer regulators internationally.8 As with any new tool, APRA will closely monitor outcomes and engage with entities to ensure the current settings are achieving their intended effect and will make adjustments if necessary.

Appendix

APRA tracks a broad range of indicators to monitor risks to the financial system. This includes four main indicators that provide a view of emerging systemic risks: credit growth and leverage; asset prices; lending conditions; and financial resilience. Trends for these select indicators are shown in the charts below.

System Risk Indicators

1. Credit Growth and Leverage

| Chart 1.1: Credit growth | Chart 1.2: Housing credit growth |

|---|---|

|  |

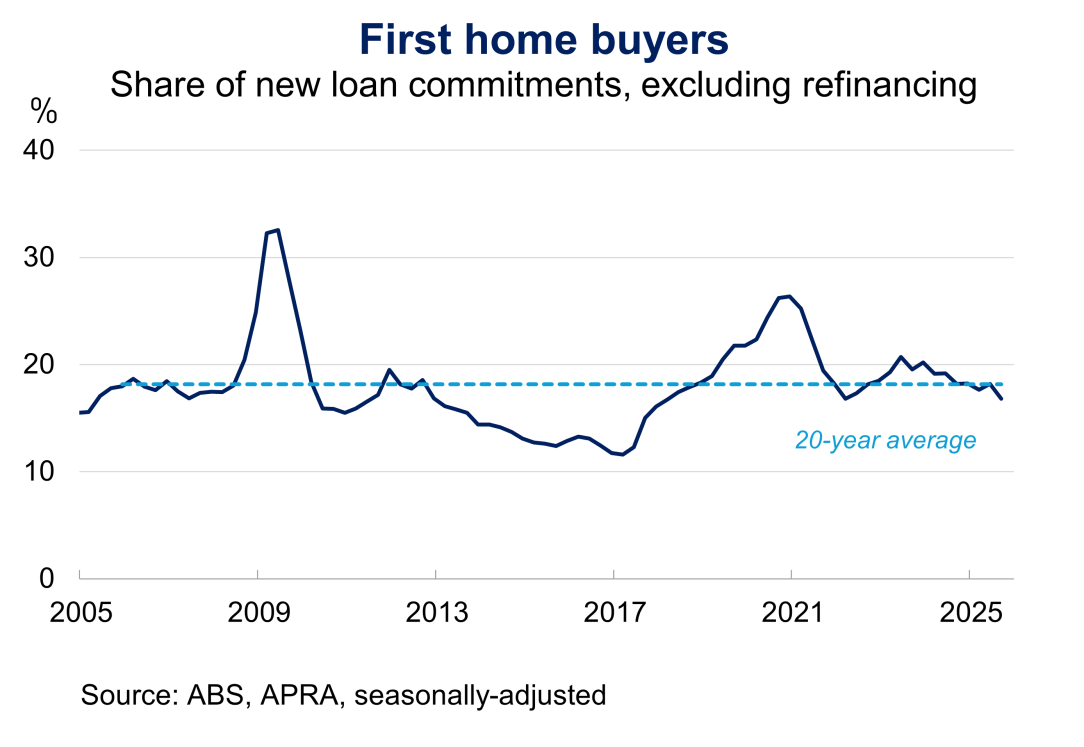

| Chart 1.3: Household debt to income | Chart 1.4: First home buyers |

|---|---|

|  |

2. Asset Prices

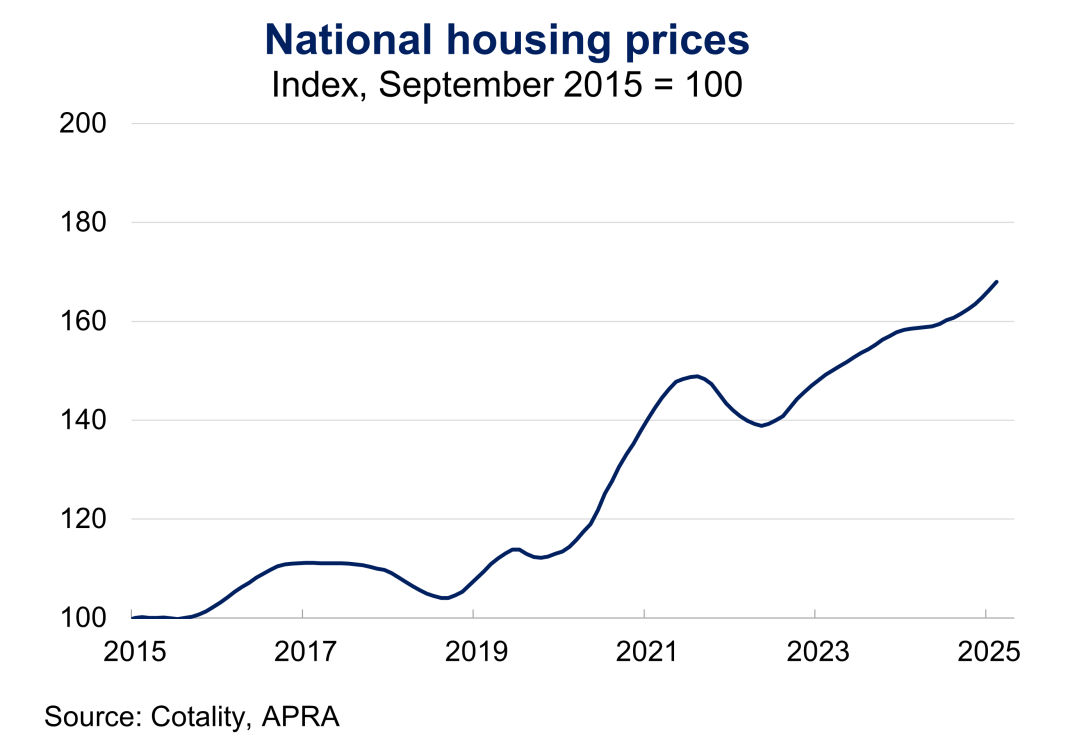

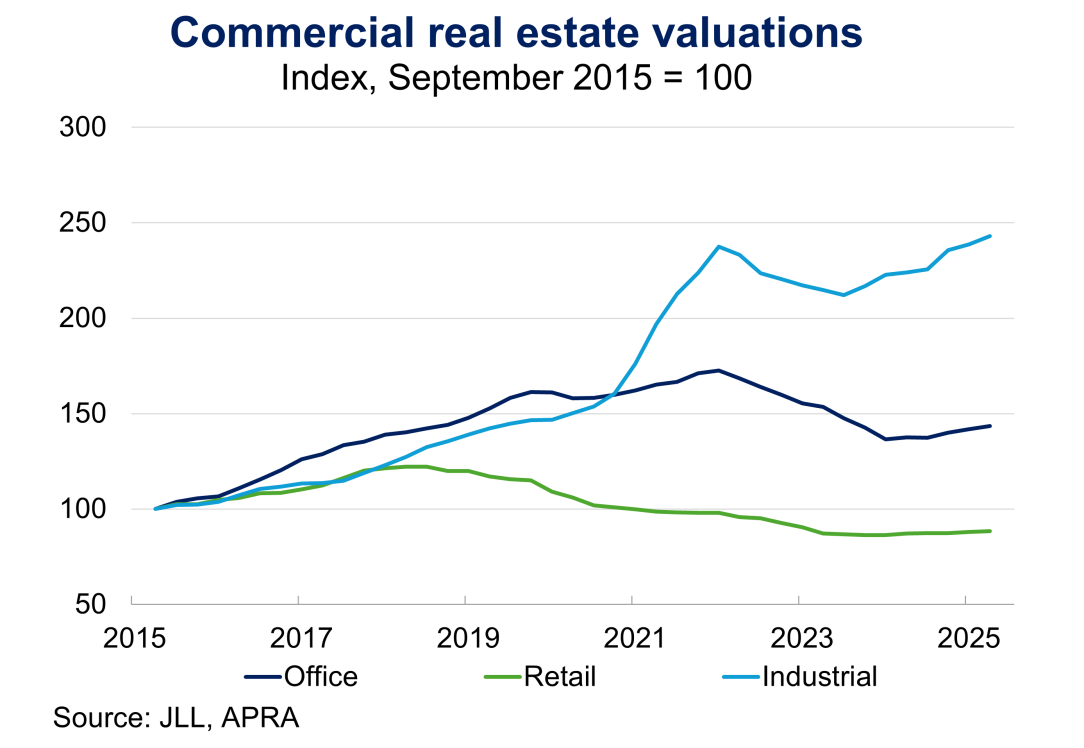

| Chart 2.1: National housing price | Chart 2.2: Commercial real estate valuations |

|---|---|

|  |

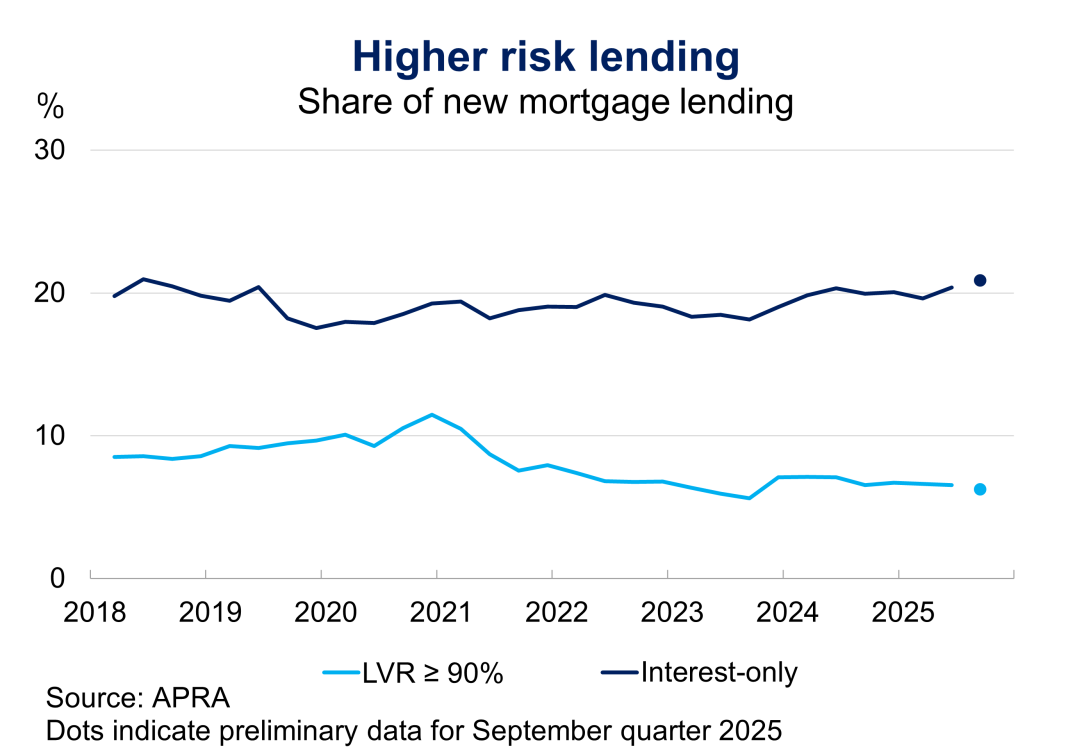

3. Lending conditions

| Chart 3.1: Debt to income ratio greater or equal to 6 times | Chart 3.2: Loan to valuation ratio greater or equal to 90 per cent and interest-only loans |

|---|---|

|  |

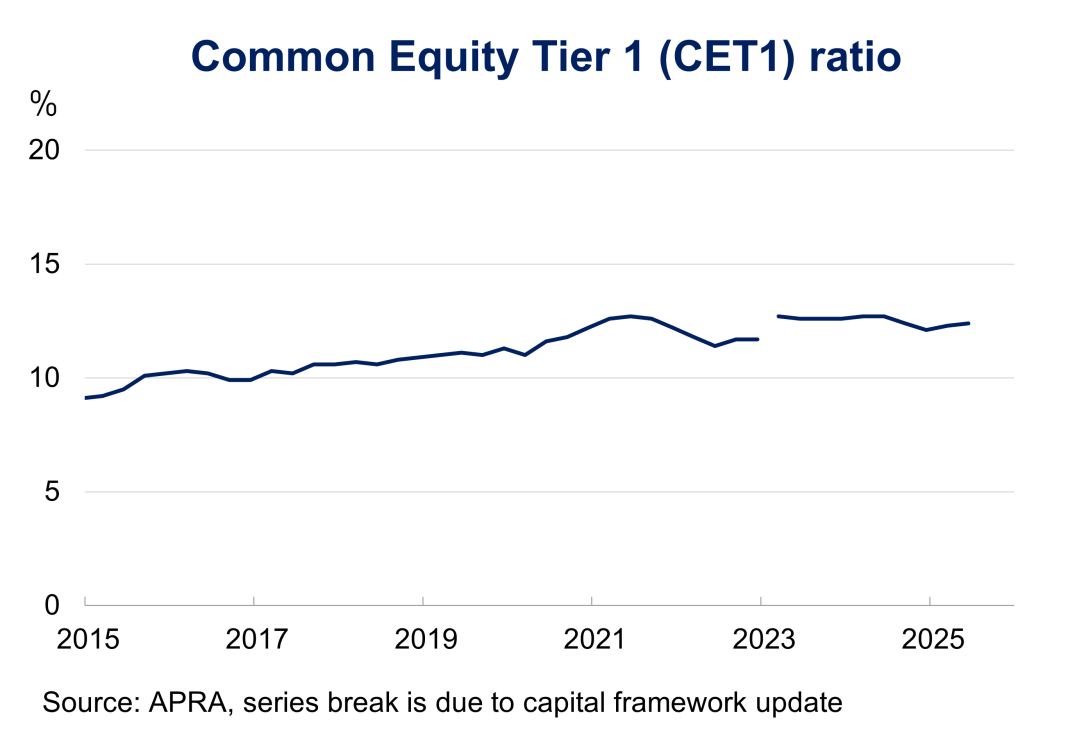

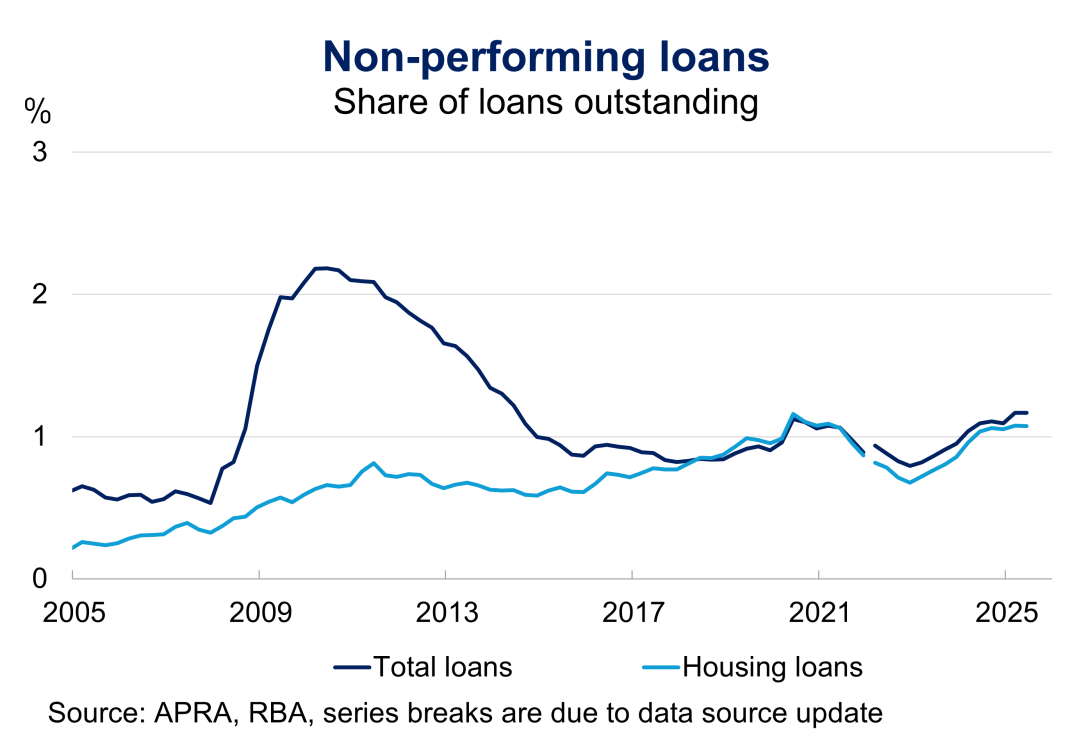

4. Financial Resilience

| Chart 4.1: Common equity tier one ratio | Chart 4.2: Non-performing loans |

|---|---|

|  |

Footnotes

1 The four members of the Council of Financial Regulators are APRA, ASIC, the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Treasury.

2 Limits on investor lending in 2014 were prompted by a combination of high and rising household debt and house prices, subdued income growth and low interest rates. There were also competitive pressures amongst lenders, leading to a loosening of loan underwriting standards and an increasing share of higher risk forms of lending, such as high LVR and interest-only loans.

3 For details, see APRA (2021) Macroprudential Policy Framework.

4 RBA (2025), ‘Financial Stability Review’, April.

5 For details, see APRA (2019), ‘Information Paper: Review of APRA's prudential measures for residential mortgage lending risks’.

6 For details, see CGFS (2023), Macroprudential policies to mitigate housing market risks and IMF (2024), Australia: 2024 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; and Staff Report in: IMF Staff Country Reports Volume 2024 Issue 360 (2024).

7 Non-ADI lenders – which currently account for around 4 per cent of total residential mortgage credit – may also see heightened demand for high DTI lending. These lenders are not subject to APRA’s active macroprudential tools, although APRA has the power to extend these tools to non-ADI lenders if they are considered to be materially contributing to instability in the financial system.

8 Other lending limits, both domestically and internationally, show that lenders often set internal management buffers below the official macroprudential limit to help with adherence. This often leads to a system-wide outcome that is below the level of the overall limit, which APRA considered when calibrating the limit.